Sulphonamides or sulpha drugs are generally known as folate synthesis inhibitors because they inhibit the synthesis of folic acid, an important precursor for the synthesis of nucleic acids in pathogenic bacteria. They are antimetabolites; and antibiotics in this category include pyrimethamine, trimethoprim, sulphamethoxazole and sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Sulphonamides are the largest antibiotic family that acts as antimetabolites; and they have activity against a wide variety of pathogenic bacteria.

Antibiotics that are antimetabolites are growth factor analogues because they competitively fight for growth precursors (e.g. folic acid) in the target organism, and thus inhibit or disrupt cell division in bacteria. By inhibiting a key step in the synthesis of folic acid (an important precursor for the biosynthesis of bacterial DNA and RNA), the sulphonamides are generally known as nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors.

SOURCES OF SULPHONAMIDES

Sulphonamides are synthetic antibacterial agents; and they are generally produced by chemical modifications of sulphanilamide (originally known as prontosil). They are not synthesized by microorganisms as is the case for the other groups of antibacterial agents.

STRUCTURE OF SULPHONAMIDES

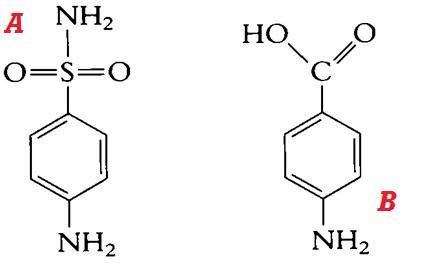

The basic structure of the sulphonamides is sulphanilamide (Figure 1A), and sulphanilamide is a structural analogue of Para-Aminobenzoic Acid, PABA (Figure 1B). Chemical modification of sulphanilamide by synthetic processes produces additional sulphonamides.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF SULPHONAMIDES

The sulphonamides are clinically used for a variety of infections caused by pathogenic bacteria especially urinary tract infections (UTIs). They are also clinically effective for treating bacterial endocarditis, otitis media, lower respiratory tract infections, rheumatic fever, chlamydial infections and nocardiosis. Sulphonamides are also used to treat some non-bacterial infections especially those caused by pathogenic protozoa. A combination of sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim have a broader spectrum of activity than any of the antibiotic used alone; and they are very effective for treating some infections caused by both Gram positive and some Gram negative rods especially in cases where resistance arises for sulphonamides.

SPECTRUM OF ACTIVITY OF SULPHONAMIDES

Sulphonamides broad spectrum antibiotics and are active against pathogenic Gram positive and some Gram negative bacteria. They are bacteriostatic in action but some antimetabolites are bactericidal.

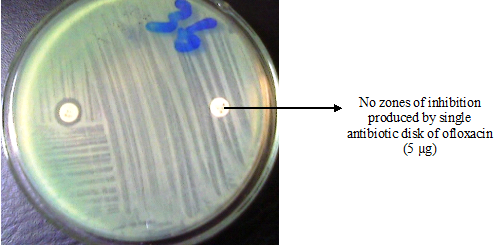

Figure 1. General structure of sulphanilamide (A) and PABA (B). Sulphonamides are structural analogues of PABA; and they compete for the enzyme (dihydropteroate synthetase) that catalyzes the conversion of PABA to dihydropteroate, required for the synthesis of folic acid in bacteria. Folic acid or folate is required for the synthesis of nucleic acids in bacteria, and their inhibition interferes with the overall cell development.

MECHANISM OR MODE OF ACTION OF SULPHONAMIDES

Sulphonamides are folate inhibitors. They compete for PABA, an important precursor required for the synthesis of folate or folic acid bacteria. Pathogenic bacteria are inefficient to synthesize folate or folic acid; and thus they derive their folic acid from PABA (a structural analogue of the sulphonamides). Humans derive their folic acid from their daily dietary intake, and this makes the sulphonamides to be selectively toxic in action. PABA is structurally synonymous to sulphonamides; and thus the antibiotic enters into reaction with PABA and competes for the active site of dihydropteroate synthetase, an important enzyme that catalyzes the combination of PABA with other precursors in the early stages of folic acid synthesis in bacteria.

Once the utilization of PABA is competitively inhibited by sulphonamides; the antibiotic becomes incorporated into the metabolic pathway for folate synthesis, and this interferes with the biosynthesis of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) in the bacteria. DNA and RNA direct cell division in bacteria; and when their synthesis is compromised (especially in the presence of antimetabolites such as the sulphonamides), bacterial growth will be inhibited and death of the pathogen may ensue.

Sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim has enhanced antibacterial activity than the earlier sulphonamides because they act at on the metabolic pathway for folate synthesis at a point after the sulphonamides; and they specifically interfere with the activity of dihydrofolate reductase, an enzyme that converts folic acid to its reduced form required by bacteria. Sulfonamides do not interfere with the metabolism of mammalian cell because humans do not synthesize folate or folic acid.

BACTERIAL RESISTANCE TO SULPHONAMIDES

The clinical efficacy of the sulphonamides is compromised by the development of resistance in some pathogenic bacteria. Pathogenic bacteria that do not utilize extracellular folic acid but synthesize their own folate are resistant to sulphonamides. Bacterial resistance to sulphonamides when used alone has necessitated the need to use sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim which produces better clinical outcome than when each of the antibiotics is used alone.

PHARMACOKINETICS OF SULPHONAMIDES

Sulphonamides are well absorbed by the body when administered orally; and they are excreted in urine.

SIDE EFFECT/TOXICITY OF SULPHONAMIDES

The sulphonamides rarely have untoward effects. However, side effects may include mild skin rashes, fever and gastrointestinal disturbances. Some patients develop hypersensitivity after the oral administration of sulphonamides.

References

Ashutosh Kar (2008). Pharmaceutical Microbiology, 1st edition. New Age International Publishers: New Delhi, India.

Axelsen P. H (2002). Essentials of Antimicrobial Pharmacology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

Balfour H. H (1999). Antiviral drugs. N Engl J Med, 340, 1255–1268.

Bean B (1992). Antiviral therapy: current concepts and practices. Clin Microbiol Rev, 5, 146–182.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Courvalin P, Leclercq R and Rice L.B (2010). Antibiogram. ESKA Publishing, ASM Press, Canada.

Denyer S.P., Hodges N.A and Gorman S.P (2004). Hugo & Russell’s Pharmaceutical Microbiology. 7th ed. Blackwell Publishing Company, USA. Pp.152-172.

Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition. Paul Singleton and Diana Sainsbury. 2006, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Canada.

Drusano G.L (2007). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antimicrobials. Clin Infect Dis, 45(suppl):89–95.

Engleberg N.C, DiRita V and Dermody T.S (2007). Schaechter’s Mechanisms of Microbial Disease. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

Finch R.G, Greenwood D, Norrby R and Whitley R (2002). Antibiotic and chemotherapy, 8th edition. Churchill Livingstone, London and Edinburg.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Gordon Y. J, Romanowski E.G and McDermitt A M (2005). A review of antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential as anti-infective drugs. Current Eye Research, 30(7): 505-515.

Hardman JG, Limbird LE, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

Joslyn, L. J. (2000). Sterilization by Heat. In S. S. Block (Ed.), Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation (5th ed., pp. 695-728). Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Katzung, B. G. (2003). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). NY, US, Lange. Kontoyiannis D.P and Lewis R.E (2002). Antifungal drug resistance of pathogenic fungi. Lancet. 359:1135–1144.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.