BIOLOGY AND CAUSATIVE AGENTS OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS

Human echinococcosis (hydatidosis, or hydatid disease) is caused by the larval stages of cestodes (tapeworms) of the genus Echinococcus. Echinococcus granulosus (sensu lato) causes cystic echinococcosis and is the form most frequently encountered. Another species, E. multilocularis, causes alveolar echinococcosis, and is becoming increasingly more common. Two exclusively New World species, E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus, are associated with “Neotropical echinococcosis”; E. vogeli causes a polycystic form whereas E. oligarthrus causes the extremely rare unicystic form.

Many genotypes of E. granulosus have been identified that differ in their distribution, host range, and some morphological features; these are often grouped into separate species in modern literature. The known zoonotic genotypes within the E. granulosus sensu lato complex include the “classical” E. granulosus sensu stricto (G1–G3 genotypes), E. ortleppi (G5), and the E. canadensis group (usually considered G6, G7, G8, and G10). Research on the epidemiology and diversity of these genotypes is ongoing, and no consensus has been reached on appropriate nomenclature thus far.

ECHINOCOCCOSIS

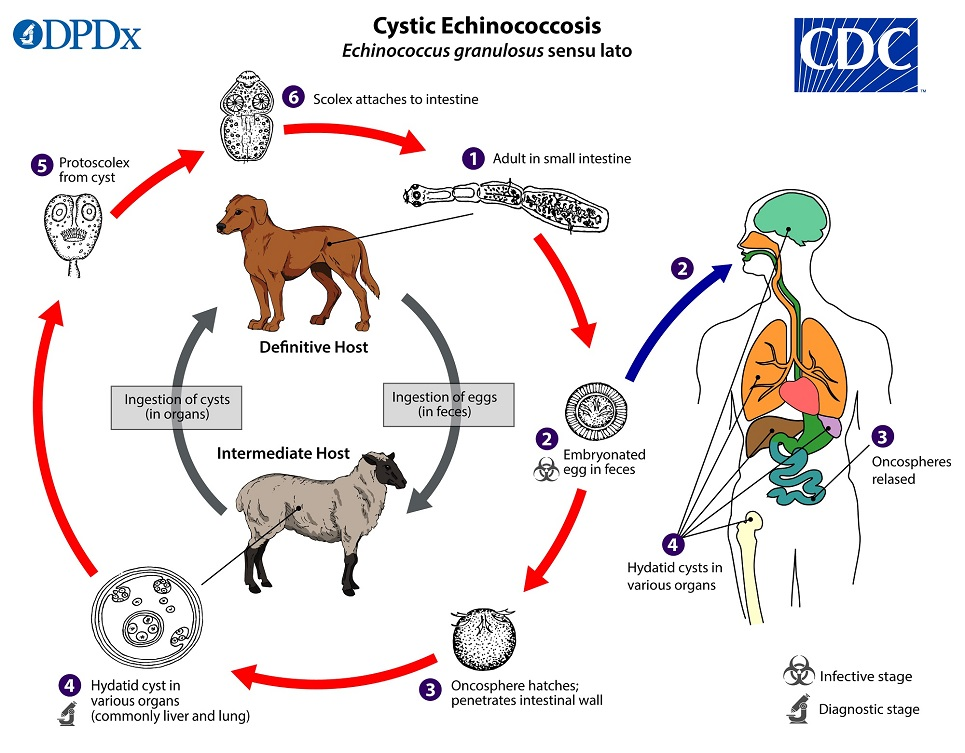

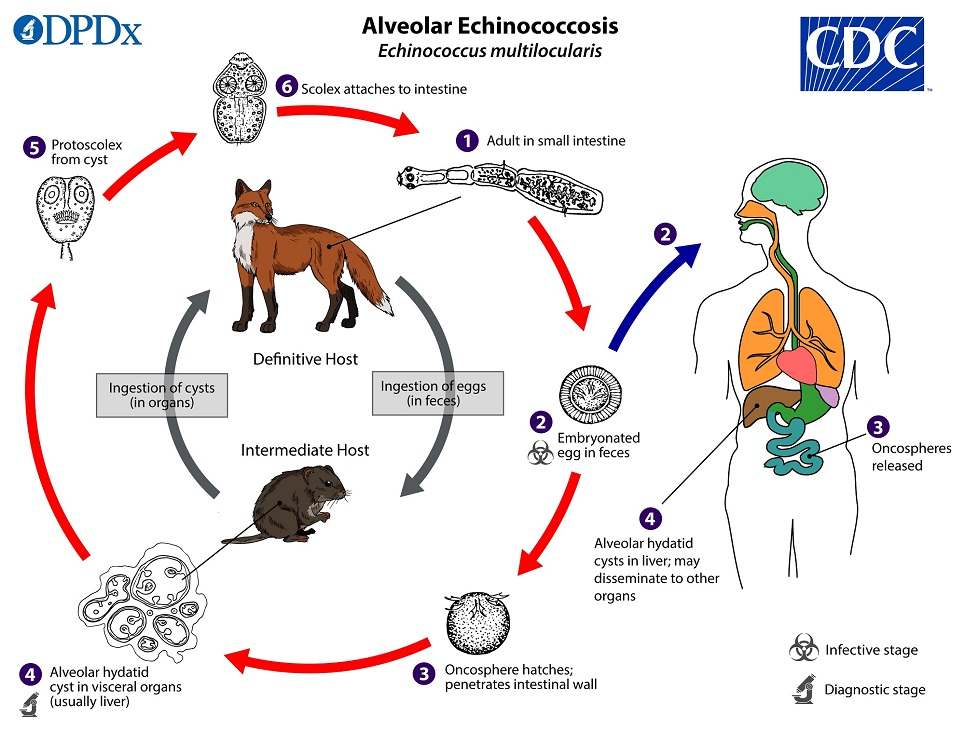

Echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by infection with tiny tapeworms of the genus Echinocococcus. Echinococcosis is classified as either cystic echinococcosis or alveolar echinococcosis. The morphological appearance of the parasite is shown in Figure 1. Alveolar and cystic echinococcosis are emerging and reemerging in Europe, Africa, and Asia. The expansion of Echinococcus spp. tapeworms in wildlife host reservoirs appears to be driving this emergence in some areas. Echinococcus spp. (family Taeniidae, class Cestoda) are zoonotic tapeworms currently infecting 2–3 million persons worldwide and causing US $200–$800 million in annual economic losses related to human infection. The cestode Echinococcus multilocularis is the causative agent of alveolar echinococcosis, a rare but potentially lethal human disease.

Cystic echinocccosis (CE), also known as hydatid disease, is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, a ~2-7 millimeter long tapeworm found in dogs (definitive host) and sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs (intermediate hosts). Although most infections in humans are asymptomatic, CE causes harmful, slowly enlarging cysts in the liver, lungs, and other organs that often grow unnoticed and neglected for years.

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) disease is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus multilocularis, a ~1-4 millimeter long tapeworm found in foxes, coyotes, and dogs (definitive hosts). Small rodents are intermediate hosts for E. multilocularis. Although cases of AE in animals in endemic areas are relatively common, human cases are rare. AE poses a much greater health threat to people than CE, causing parasitic tumors that can form in the liver, lungs, brain, and other organs. If left untreated, AE can be fatal.

NEOTROPICAL ECHINOCOCCOSIS (ECHINOCOCCUS VOGELI, E. OLIGARTHRUS)

The Neotropical agents follow the same life cycle although with differences in hosts, morphology, and cyst structure. Adults of E. vogeli reach up to 5.6 mm long, and E. oligarthrus up to 2.9 mm. Cysts are generally similar to those found in cystic echinocccosis but are multi-chambered.

HOSTS OF ECHINOCOCCUS PARASITES

Echinococcus granulosus definitive hosts are wild and domestic canids. Natural intermediate hosts depend on genotype. Intermediate hosts for zoonotic species/genotypes are usually ungulates, including sheep and goats (E. granulosus sensu stricto), cattle (“E. ortleppi”/G5), camels (“E. canadensis”/G6), and cervids (“E. canadensis”/G8, G10).

For E. multilocularis, foxes, particularly red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), are the primary definitive host species. Other canids including domestic dogs, wolves, and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) are also competent definitive hosts. Many rodents can serve as intermediate hosts, but members of the subfamily Arvicolinae (voles, lemmings, and related rodents) are the most typical.

The natural definitive host of E. vogeli is the bush dog (Speothos venaticus), and possibly domestic dogs. Pacas (Cuniculus paca) and agoutis (Dasyprocta spp.) are known intermediate hosts. E. oligarthrus uses wild neotropical felids (e.g. ocelots, puma, jaguarundi) as definitive hosts, and a broader variety of rodents and lagomorphs as intermediate hosts.

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF ECHINOCOCCUS PARASITES

Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato occurs practically worldwide, and more frequently in rural, grazing areas where dogs ingest organs from infected animals. The geographic distribution of individual E. granulosus genotypes is variable and an area of ongoing research. The lack of accurate case reporting and genotyping currently prevents any precise mapping of the true epidemiologic picture. However, genotypes G1 and G3 (associated with sheep) are the most commonly reported at present and broadly distributed. In North America, Echinococcus granulosus is rarely reported in Canada and Alaska, and a few human cases have also been reported in Arizona and New Mexico in sheep-raising areas. In the United States, most infections are diagnosed in immigrants from counties where cystic echinococcosis is endemic. Some genotypes designated “E. canadensis” occur broadly across Eurasia, the Middle East, Africa, North and South America (G6, G7) while some others seem to have a northern holarctic distribution (G8, G10).

E. multilocularis occurs in the northern hemisphere, including central and northern Europe, Central Asia, northern Russia, northern Japan, north-central United States, northwestern Alaska, and northwestern Canada. In North America, Echinococcus multilocularis is found primarily in the north-central region as well as Alaska and Canada. Rare human cases have been reported in Alaska, the province of Manitoba, and Minnesota. Only a single autochthonous case in the United States (Minnesota) has been confirmed.

E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus occur in Central and South America.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION (SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS) OF ECHINOCOCCUS PARASITES

Echinococcus granulosus infections often remain asymptomatic for years before the cysts grow large enough to cause symptoms in the affected organs. The rate at which symptoms appear typically depends on the location of the cyst. Hepatic and pulmonary signs/symptoms are the most common clinical manifestations, as these are the most common sites for cysts to develop In addition to the liver and lungs, other organs (spleen, kidneys, heart, bone, and central nervous system, including the brain and eyes) can also be involved, with resulting symptoms. Rupture of the cysts can produce a host reaction manifesting as fever, urticaria, eosinophilia, and potentially anaphylactic shock; rupture of the cyst may also lead to cyst dissemination.

Echinococcus multilocularis affects the liver as a slow growing, destructive tumor, often with abdominal pain and biliary obstruction being the only manifestations evident in early infection. This may be misdiagnosed as liver cancer. Rarely, metastatic lesions into the lungs, spleen, and brain occur. Untreated infections have a high fatality rate.

Echinococcus vogeli affects mainly the liver, where it acts as a slow growing tumor; secondary cystic development is common. Too few cases of E. oligarthrus have been reported for characterization of its clinical presentation.

PATHOGENESIS OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS INFECTION/DISEASE

Persons with cystic echinococcosis often remain asymptomatic until hydatid cysts containing the larval parasites grow large enough to cause discomfort, pain, nausea, and vomiting. The cysts grow over the course of several years before reaching maturity and the rate at which symptoms appear typically depends on the location of the cyst (Figure 2). The cysts are mainly found in the liver and lungs but can also appear in the spleen, kidneys, heart, bone, and central nervous system, including the brain and eyes. Cyst rupture is most frequently caused by trauma and may cause mild to severe anaphylactic reactions, even death, as a result of the release of cystic fluid.

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is characterized by parasitic tumors in the liver and may spread to other organs including the lungs and brain. In humans, the larval forms of E. multilocularis do not fully mature into cysts but cause vesicles that invade and destroy surrounding tissues and cause discomfort or pain, weight loss, and malaise (Figure 3). AE can cause liver failure and death because of the spread into nearby tissues and, rarely, the brain. AE is a dangerous disease resulting in a mortality rate between 50% and 75%, especially because most affected people live in remote locations and have poor health care.

DIAGNOSIS OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS INFECTION

The presence of a cyst-like mass in a person with a history of exposure to sheepdogs in an area where E. granulosus is endemic suggests a diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Imaging techniques, such as CT scans, ultrasonography, and MRIs, are used to detect cysts. After a cyst has been detected, serologic tests may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Alveolar echinococcosis is typically found in older people. Imaging techniques such as CT scans are used to visually confirm the parasitic vesicles and cyst-like structures and serologic tests can confirm the parasitic infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS INFECTION

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus. CE is found in Africa, Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Central and South America, and in rare cases, North America. The parasite is transmitted to dogs when they ingest the organs of other animals that contain hydatid cysts. The cysts develop into adult tapeworms in the dog. Infected dogs shed tapeworm eggs in their feces which contaminate the ground. Sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs ingest tapeworm eggs in the contaminated ground; once ingested, the eggs hatch and develop into cysts in the internal organs. The most common mode of transmission to humans is by the accidental consumption of soil, water, or food that has been contaminated by the fecal matter of an infected dog. Echinococcus eggs that have been deposited in soil can stay viable for up to a year. The disease is most commonly found in people involved in raising sheep, as a result of the sheep’s role as an intermediate host of the parasite and the presence of working dogs that are allowed to eat the offal of infected sheep.

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus multilocularis. AE is found across the globe and is especially prevalent in the northern latitudes of Europe, Asia, and North America. The adult tapeworm is normally found in foxes, coyotes, and dogs. Infection with the larval stages is transmitted to people through ingestion of food or water contaminated with tapeworm eggs.

TREATMENT OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS INFECTION

In the past, surgery was the only treatment for cystic echinococcal cysts. Chemotherapy, cyst puncture, and PAIR (percutaneous aspiration, injection of chemicals and reaspiration) have been used to replace surgery as effective treatments for cystic echinococcosis. However, surgery remains the most effective treatment to remove the cyst and can lead to a complete cure. Some cysts are not causing any symptoms and are inactive; those cysts often go away without any treatment.

The treatment of alveolar echinococcosis is more difficult than cystic echinococcosis and usually requires radical surgery, long-term chemotherapy, or both.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF ECHINOCOCOCCUS INFECTION

Cystic echinococcosis is controlled by preventing transmission of the parasite. Prevention measures include limiting the areas where dogs are allowed and preventing animals from consuming meat infected with cysts.

- Prevent dogs from feeding on the carcasses of infected sheep.

- Control stray dog populations.

- Restrict home slaughter of sheep and other livestock.

- Do not consume any food or water that may have been contaminated by fecal matter from dogs.

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water after handling dogs, and before handling food.

- Teach children the importance of washing hands to prevent infection.

Alveolar echinococcosis can be prevented by avoiding contact with wild animals such as foxes, coyotes, and dogs and their fecal matter and by limiting the interactions between dogs and rodent populations.

- Do not allow dogs to feed on rodents and other wild animals.

- Avoid contact with wild animals such as foxes, coyotes and stray dogs.

- Do not encourage wild animals to come close to your home or keep them as pets.

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water after handling dogs or cats, and before handling food.

- Teach children the importance of washing hands to prevent infection.

FURTHER READING

Chiodini P.L., Moody A.H., Manser D.W (2001). Atlas of medical helminthology and protozoology. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Ghosh S (2013). Paniker’s Textbook of Medical Parasitology. Seventh edition. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers,

Gillespie S.H and Pearson R.D (2001). Principles and Practice of Clinical Parasitology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. West Sussex, England.

Gutierrez Y (2000). Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

John D and Petri W.A Jr (2013). Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. Ninth edition.

Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E and Dolin R (2000). Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Roberts L, Janovy J (Jr) and Nadler S (2012). Foundations of Parasitology. Ninth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Schneider M.J (2011). Introduction to Public Health. Third edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, Massachusetts, USA.

Discover more from #1 Microbiology Resource Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.