Plasmids are extrachromosomal DNA molecules found in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic microorganisms that have the ability to replicate independently. In prokaryotes, plasmids are found in both Gram positive bacteria and Gram negative bacteria; and they usually range from 1.5 kb to 300 kb in size. In terms of the strands of their DNA molecule, most bacterial plasmids are dsDNA molecules while others are ssDNA molecules.

Plasmids are circular piece of autonomously replicating DNA that may express antibiotic resistance gene and can also be engineered to express a particular protein of interest. A plasmid controls its own replication by using the biosynthetic machinery of its host cell to make other plasmid-encoded protein molecules or materials that are needed for a particular function. Plasmids are different from the chromosome of the organism even though they may be found in the same organism.

In a microorganism (e.g., bacteria), there are a number of genetic materials that are found besides the organism’s chromosome. These genetic materials include plasmids, transposons, integrons, and other genomes which in addition to the chromosome help in the survival of the organism. Plasmids which originally evolved from bacterial cells are extrachromosomal DNA molecule of bacteria that can replicate independently of the organisms’ own chromosome (Figure 2). Though they naturally occur in bacterial cells, plasmids can also be found in eukaryotic cells.

Many plasmids encode products or functions which modify the phenotype of the host cell. For example, a given bacterial cell may harbour plasmid that confers antibiotic resistance traits or property on the organism. Certain experiments such as gel electrophoresis or plasmid curing experiments (using mutagens such as acridine orange dye) may be used to determine whether a particular bacterial cell harbour a plasmid or not.

The presence of a plasmid in a bacterial cell may often be inferred by the host cell’s phenotype (for example: resistance to a particular antibiotic) since certain properties in an organism such as antibiotic resistance are commonly plasmid-specified or plasmid-mediated. The loss of this particular phenotypic property or function in the organism after treating the host cell with chemical agents that specifically kills its plasmid – will help the researcher to know confirm the presence of plasmid in the organism.

Plasmids are not necessary required for the growth of bacterial cell but rather possess some unique features (e.g. antibiotic resistance ability) that give them some selective advantage over other materials in a bacterial cell. Plasmids have no extracellular form and they are normally smaller in size than the bacterial chromosome. They are known to be generally circular and double-stranded DNA molecules, though some linear plasmids also exist. Plasmids are different from an organism’s chromosome in that the chromosome contains genes that are necessary for cellular functions while plasmids rarely contain such important genes required for the growth of an organism.

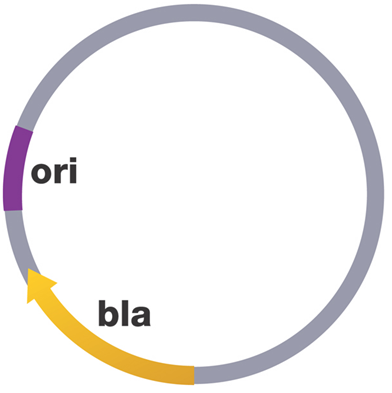

They are found in different numbers in an organism, and this ranges from one plasmid per cell to hundreds of plasmids per cell (a phenomenon called copy number). Plasmids are indispensable tools in recombinant DNA technology (genetic engineering) because of their inherent antibiotic resistance marker, small molecular size and high copy number during replication. The plasmids that are used in recombinant DNA technology to transfer genes from one organism to another are generally classified as vectors. Bacterial plasmids have one or more DNA sequence which serve as the origin of replication or ori (Figure2).

Ori is the starting point for plasmid DNA replication in the organism. It also help the bacterial plasmid DNA to be duplicated autonomously (i.e. on its own) from the host’s chromosome. In addition to the ori, plasmids also have sites for the expression of antibiotic resistance genes such as the beta-lactamase or bla genes. The site for the expression of beta-lactamase genes or (bla genes) could also serve as important location for the insertion of other gene of interest into a recipient bacterial cell.

Plasmids are veritable tools in the hands of molecular biologists for bacterial transformation. Plasmids are the easiest cloning vectors to work with; and a piece of plasmid can be used to clone a mixture of DNA fragments. Plasmids are known to possess sites for antibiotic resistance genes, and this allows for easy detection of recombinant plasmids after a transformation experiment in the laboratory.

Plasmids are important tools for gene cloning techniques, and they are also applied in a wide variety of recombinant DNA technology applications. Plasmid vectors usually contain three sites which makes them unique and widely used for molecular biology manipulations. Restriction site or cloning site, drug resistance gene or marker and a replication origin (ORI) are the main constituents of a plasmid vector.

Restriction or cloning site is the site or region on the plasmid vector where the foreign or exogenous DNA fragment could be inserted. Drug resistant gene or marker is the region that harbours gene that destroys antibiotics (e.g. ampicillin); and this particular region allows for the selective growth and isolation of the plasmid vector in a host cell or in vitro after the gene cloning process. Ori is the region that allows the plasmid vector to replicate the gene of interest it is carrying within its host organism.

The insertion of a foreign piece of DNA into the ampicillin resistance gene of a plasmid makes that particular plasmid to be susceptible to the antibiotic ampicillin i.e. the recombinant plasmid will no longer confer resistance to ampicillin. Bacterial transformants lacking such ability to confer resistance to a particular antibiotic (in this case: ampicillin) because of transformation are said to contain a chimeric plasmid.

Chimera is a recombinant plasmid that contains a foreign DNA. Plasmids are the first cloning vectors, and they are easier to isolate and purify after a cloning experiment, thus aiding detection of transformed plasmids. Other examples of cloning vectors include: cosmids, yeast artificial chromosome (YAC), bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC), viral and phage vectors.

CLASSIFICATION OF PLASMIDS

Plasmids can be classified based on their ability to transfer genetic material and based on the function that they perform in their host organism.

- Their ability to transfer their genetic material or gene to other bacteria. Such plasmids are called conjugative plasmids; and they contain or carry a set of genes called tra (for transfer) genes which coordinates the process of conjugation in plasmids (i.e. the sexual transfer of plasmid to susceptible bacterium).

Only plasmids with the tra region (i.e. region that contains the tra genes) can successfully carry out conjugation because this region on the plasmid contains genes that encodes proteins that functions in bacterial mating process, DNA replication and DNA transfer. Some conjugative plasmids have a wide variety of microorganisms that they can transfer their genes to.

This ability is significant because such bacterial plasmids can transfer their genes (e.g. those for antibiotic resistance) to related and non-related organisms, consequently affecting a broad range of both Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria.

- Their specific function in their host organism. For example, some plasmids can confer on an organism the exceptional ability to build resistance against an antimicrobial agent (such plasmids are called R plasmid), some are virulent (i.e. they can turn an organism into becoming a pathogen) and others are degradative (i.e. they can breakdown substances).

Types of plasmids

- Resistance Plasmids: These are plasmids that confer on a bacterium the exceptional ability to resist the antimicrobial onslaught of antimicrobial agents or antibiotics. Resistance or R plasmids contain genes that help a bacterial cell defend against environmental factors such as poisons or antibiotics. Some resistance plasmids can transfer themselves through conjugation. When this happens, a strain of bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics.

- Virulence Plasmids: These are plasmid that turns a bacterium from a non-pathogenic strain to a pathogenic strain capable of causing infectious disease. When a virulence plasmid is inside a bacterium, it turns that bacterium into a pathogen, which is an agent of disease. Bacteria that cause disease can be easily spread and replicated among affected individuals.

- Degradative Plasmids: These are plasmids that confer on bacteria the ability to degrade or break down recalcitrant compounds or molecules in the environment. Degradative plasmids help the host bacterium to digest compounds that are not commonly found in nature, such as camphor, xylene, toluene, and salicylic acid. These plasmids contain genes for special enzymes that break down specific compounds.

- Col Plasmids: Col stands for colicins, referring to special genes carried by bacteria that mediate the production of certain compounds or proteins that kill other bacteria. Col plasmids contain genes that make bacteriocins (also known as colicins), which are proteins that kill other bacteria and thus defend the host bacterium.

- Fertility (F) Plasmids: Fertility plasmids, also known as F-plasmids, contain transfer genes that allow genes to be transferred from one bacteria to another through the genetic transfer process known as conjugation.

References

Ashutosh Kar (2008). Pharmaceutical Microbiology, 1st edition. New Age International Publishers: New Delhi, India.

Bisht R., Katiyar A., Singh R and Mittal P (2009). Antibiotic Resistance – A Global Issue of Concern. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research, 2 (2):34-39.

Courvalin P, Leclercq R and Rice L.B (2010). Antibiogram. ESKA Publishing, ASM Press, Canada.

Denyer S.P., Hodges N.A and Gorman S.P (2004). Pharmaceutical Microbiology. 7th ed. Blackwell Publishing Company, USA.

Fernandes Prabhavathi (2006). Antibacterial discovery – the failure of success? Nature Biotechnology, 24(12):1.

Finch R.G, Greenwood D, Norrby R and Whitley R (2002). Antibiotic and chemotherapy, 8th edition. Churchill Livingstone, London and Edinburg.

Hart C.A (1998). Antibiotic Resistance: an increasing problem? BMJ, 316:1255-1256.

Jayaramah R (2009). Antibiotic Resistance: an overview of mechanisms and a paradigm shift. Current Science, 96(11):1475-1484.

Mascaretti O.A (2003). Bacteria versus antibacterial agents: An integrated approach. Washington: ASM Press.

Mascaretti O.A (2003). Bacteria versus antimicrobial agents: An Integrated Approach. Washington: ASM Press.

Mazel D and Davies J (1998). Antibiotic Resistance: The Big Picture. In B. Rosen and S. Mobashery (Eds). Resolving the antibiotic paradox: progress in understanding drug resistance and developments of new antibiotics. New York: Plenum Press.

Russell A.D and Chopra I (1996). Understanding antibacterial action and resistance. 2nd edition. Ellis Horwood Publishers, New York, USA.

Sundsfjord A., Simonsen G.S., Haldorsen B.C., Haaheim H., Hjelmevoll S., Littauer P and Dahl K.H (2004). Genetic methods for detection of antimicrobial resistance. APMIS, 112:815-37.

Twyman R.M (1998). Advanced Molecular Biology: A Concise Reference. Bios Scientific Publishers. Oxford, UK.

Weaver R.F (2005). Molecular Biology. Third edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Willey J.M, Sherwood L.M and Woolverton C.J (2008). Harley and Klein’s Microbiology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, USA.

Discover more from #1 Microbiology Resource Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.