Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative, encapsulated, lactose-fermenting, non-motile, facultative rod in the genus Klebsiella and family Enterobacteriaceae. In addition to O and H antigens, K. pneumoniae possess K antigens (that consists mainly of polysaccharides). K antigens are capsular antigens found mostly amongst members of the Enterobacteriaceae family; and in the case of K. pneumoniae, the K antigens are usually external to the somatic antigens (O and H) of the pathogen. K. pneumoniae is a less common pathogen of the intestinal tract of humans and animals than E. coli. K. pneumoniae is notorious in causing bloodstream infections and severe pneumonia in humans.

However, Klebsiella species are most commonly found in the soil and water, and some are nitrogen (N2)-fixing bacteria. K. pneumoniae is a well-studied N2-fixing bacterium that is free-living and exists as a chemoorganotroph in the soil. Unlike other N2-fixers that go into association with other higher organisms such as plants before they can use N2 as their sole source of nitrogen, K. pneumoniae is a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium and does not need to go into association with any other organism to carryout N2-fixation. This is because K. pneumoniae and other free-living N2-fixers contain the enzyme nitrogenase –that reduces N2 to ammonia.

Nitrosomonas and Rhizobium species are typical examples of bacteria that form symbiotic association with certain types of plants (e.g. legumes) before they can carry out the process of N2-fixation in the ecosystem. Pseudomonas, Azotobacter, Azomonas, Bacillus, Acetobacter, Alcaligenes and Cyanobacteria are some examples of the genus that contain other free-living N2-fixing bacteria. Generally, K. pneumoniae is mostly implicated as the main causative agent of nosocomial- and community-acquired pneumonia and some UTI.

PATHOGENESIS OF KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

K. pneumoniae like P. aeruginosa causes opportunistic infections in humans. Persons with history of type I diabetes (i.e. diabetes mellitus), alcoholism, respiratory infections and malnutrition are most often affected. The elderly and individuals with weakened immunity are also prone to K. pneumoniae infections. The human colon and respiratory tract are the main reservoir of K. pneumoniae in the body. Some healthy people harbour K. pneumoniae in their respiratory tract and may be prone to a pneumonia anytime their immunity becomes compromised or is weakened.

The pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae is enhanced by its large polysaccharide capsules and its ability to produce toxins and other extracellular factors as is typical to members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. The capsule produced by K. pneumoniae obstructs phagocytosis in the host while the endotoxin causes inflammation, fever and septic shock. K. pneumoniae reaches the lungs where it produces pneumonia (different from that caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae) via inhalation of respiratory droplets from the upper respiratory tract of individuals harbouring the pathogen.

A thick, bloody sputum known as currant-jelly sputum is the main clinical symptom presented in individuals whose pneumonia is caused by K. pneumoniae. Aside pneumonia and UTI, bacteraemia and sepsis are other clinical episodes associated with an infection with K. pneumoniae. Feacal contamination of catheters can result to a UTI, an invasion of IV lines and/or bowel defects in individuals with weakened immune system may result in sepsis.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

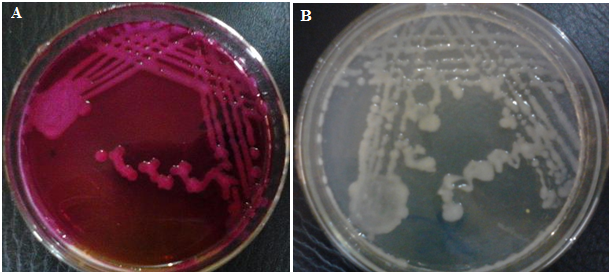

Microscopy, isolation and identification of the pathogen is often the mainstay of diagnosing any infection in which K. pneumoniae is implicated or suspected. K. pneumoniae is Gram-negative and non-motile. Characteristically, K. pneumoniae produces mucoid colonies on growth media. K. pneumoniae grows on differential media including MacConkey agar producing pink-mucoid colonies (Figure 1) and CLED (producing yellow-mucoid colonies). On blood agar, K. pneumoniae produces large grey or pale mucoid colonies. Biochemically, K. pneumoniae is urease positive, lactose-fermenting and citrate positive. It is also positive to malonate utilization test and lysine decarboxylase (LDC) test. Some species of Klebsiella (e.g. K. oxytoca) is indole positive.

IMMUNITY TO KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

K. pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen and rarely cause infection or disease in people with intact immune system. No known form of protection is established in individuals infected with the pathogen but the humoral immune system mechanism plays active role in containment of K. pneumoniae via opsonization and/or phagocytosis.

TREATMENT OF KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

The treatment of K. pneumoniae infection should be guided by a proper susceptibility test result owing to the nature of the pathogen to produce extracellular substances including beta-lactamases that render antimicrobial agents directed towards it ineffective. Some strains of Klebsiella especially those associated with hospital-acquired infections are multidrug resistant; and thus, the treatment of K. pneumoniae infection should be embarked using multiple antibiotic regimens. Third-generation cephalosporins and aminoglycosides are often used for the treatment of both nosocomial and community-acquired K. pneumoniae infections.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

The control of K. pneumoniae infection in the community and around hospital settings depends on ensuring proper infection control strategies when handling patients and using invasive and non-invasive medical devices (e.g. catheters, respirators and IV lines). These medical devices known to spread the pathogen should be used cautiously and only when needed.

OTHER SPECIES OF KLEBSIELLA

- K. oxytoca: K. oxytoca is a diazotroph (i.e. it is able to colonies plant hosts and fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form which the plant can use. Diazotrophs are bacteria and archaea that fix atmospheric nitrogen gas into a more usable form such as ammonia; and examples include Klebsiella species, Rhizobium species, Azospirillum species and Azotobacter species. K. oxytoca causes septicaemia and colitis in humans; and they are implicated in other nosocomial infections.

- K. rhinoscleromatis: K. rhinoscleromatis is the causative agent of rhinoscleroma. Rhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous condition of the nose and other structures of the upper respiratory tract. K. rhinoscleromatis can be transmitted from person-to-person via airborne secretions; but prolonged contact with infected individuals is required for infection.

- K. ozaenae: Klebsiella ozaenae causes ozena, a primary atrophic rhinitis (AR) which involves chronic inflammation of the nose. It is also associated with rare cases of cerebral abscess and meningitis.

- Klebsiella variicola: Klebsiella variicola is pathogenic in humans and plants.

- Klebsiella granulomatis: Klebsiella granulomatis is pathogenic to humans. K. granulomatis are sexually transmitted; and they may also be vertically transmitted (from mother to child). They can also be acquired directly by accidental inoculation.

- Klebsiella singaporensis: Klebsiella singaporensis is found in the soil; and it is especially associated with the roots of sugar cane plants. K. singaporensis is a novel species of Klebsiella and its pathogenicity to humans is yet to be determined.

References

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of microorganisms. 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Publishers. USA. Pp.795-796.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA. Pp. 296-299.

Ryan K, Ray C.G, Ahmed N, Drew W.L and Plorde J (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Singleton P and Sainsbury D (1995). Dictionary of microbiology and molecular biology, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Discover more from #1 Microbiology Resource Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.