Helicobacter pylori bacterium is a microaerophilic, urease-producing, Gram-negative, motile, urease-positive, oxidase-positive, catalase-positive and spiral-shaped bacterium that inhabits the stomach, intestinal tract and oral cavity of human beings and other animals. H. pylori were first discovered in the early 1980’s as the causative agent of ulcer and they were formerly classified as Campylobacter pylori due to some of the biological similarities that they possess with bacteria in the Campylobacter genus. A member of the normal flora of the stomach, H. pylori is the main etiologic agent of peptic ulcer and gastric ulcer and other gastrointestinal-associated infections in susceptible humans.

The duo of peptic and gastric ulcer have also been associated with stomach cancer in H. pylori infected persons. H. pylori is notorious in producing large amount of urease enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of urea (H2N-CO-NH2) to ammonia (NH3) and carbondioxide (CO2) in the stomach of humans (known for its very low pH level). This reaction creates an alkaline environment that allows H. pylori to comfortably inhabit the acidity of the gastric mucosa in the stomach (which is acidic in nature due to the production of gastric acid).

PATHOGENESIS OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

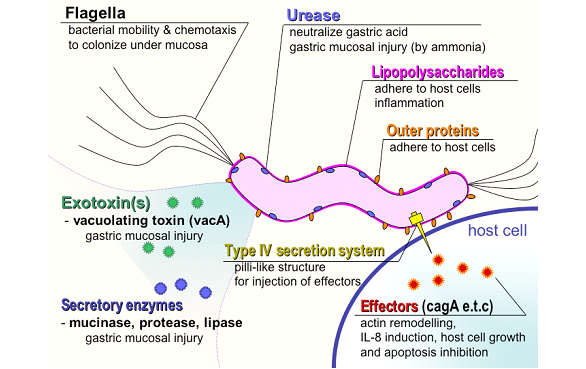

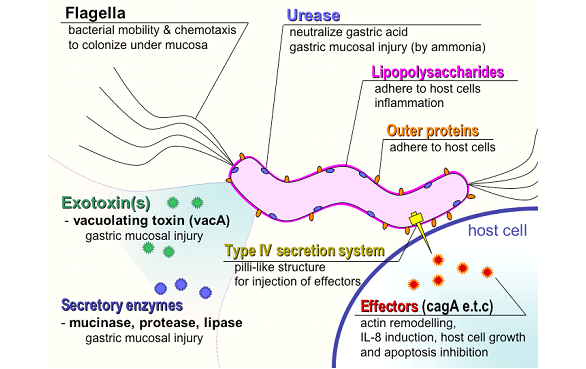

The pathogenesis of H. pylori is complex and not well understood. It causes both symptomatic and asymptomatic type of gastric ulcers in humans. Humans are the only known hosts for H. pylori and animal reservoirs for the organism rarely exist. H. pylori is usually spread via the feacal-oral route through contaminated food and water. After invasion, H. pylori, a rapidly motile bacterium migrates to the mucosal wall of the stomach where it firmly attaches to epithelial cellsusing its surface proteins. This sparks up an inflammatory reaction in the gastric mucosa which ultimately results to ulceration and cell damage.

Vomiting, persistent abdominal pains, bloating, belching, black stooling; extensive bleeding (in ulcerative patients) and nausea are some of the clinical signs and symptoms of H. pylori infections. A lot of H. pylori infected individuals experience mild chronic gastritis and may remain asymptomatic for many years while others experience ulceration of the duodenum and other forms of gastritis which consummate into an ulcer. The production of urease by H. pylori creates an alkaline environment (due to an elevated pH level) by urea hydrolysis to produce ammonia (NH3), and this phenomenon enhances the pathogenicity and/or virulence of the pathogen (Figure 1).

Alkaline environment initiated by H. pylori via its urease activity protects the organism from the harsh acidic condition of the stomach especially the gastric mucosal cells which they are known to colonize. In addition to urease, H. pylori also produce a number of virulence factors such as cytotoxins and enzymes and/or proteins that boosts its pathogenicity.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

H. pylori infection can be diagnosed in two ways which are invasive and noninvasive methods. In the invasive method, the mucosal region of the stomach is examined by endoscopy or gastroscopy. Noninvasive techniques include the use of a urea breathe test, histological examination of gastric biopsies, serological tests for detecting antibodies in serum and culture of gastric specimens for pathogen identification.

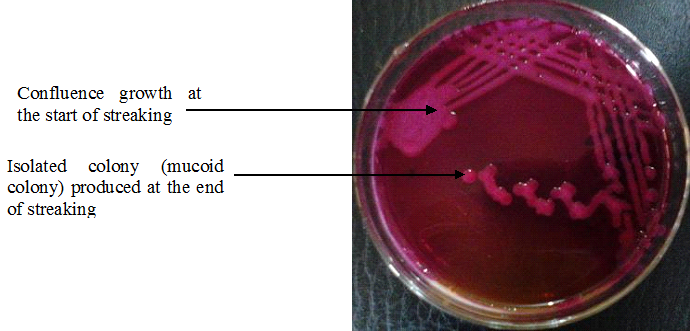

H. pylori is a microaerophilic bacterium, and it can grow in Christensen’s urea broth and blood agar once provided a microaerophilic environment inclusive of CO2 presence. Biochemically, H. pylori test positive to oxidase, urease and catalase; and the bacterium can also be demonstrated in Gram staining or Giemsa stain technique.

In the urea breathe test, individuals suspected of having H. pylori infection are given a radioactive labeled urea (e.g. 14C) which they ingest. H. pylori positive persons produce radioactive CO2 as a result of urease activity in the host, and this is detected in the breath of the individual using a specialized instrument. Urease detection is diagnostic of H. pylori infection.

IMMUNITY TO HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

Immunity against H. pylori infection is usually rapid and substantial following the production of IgM and IgG in infected individuals. However, protection may not be long-lasting, and thus infected persons are usually prone to recurrence of the infection.

TREATMENT OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

Lasting cure of peptic ulcer and gastric ulcer due to H. pylori invasion is usually achieved using bismuth salts and antibiotics such as erythromycin, tetracycline, metronidazole, clarithromycin and amoxycillin. The use of protein-pump inhibitors (e.g. omeprazole) inhibits urease production and H. pylori. The combination of omeprazole with antibiotics such as metronidazole, clarithromycin or amoxycillin is effective in clearing the infection.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

There is no specific preventive measure against H. pylori infection in human population. However, since transmission of H. pylori is usually via the feacal-oral route, people should avoid feacal contamination of their hands, food or water. H. pylori infected persons should be properly treated using the required antimicrobials, and patients should ensure to always take the full course of their regimens in order to clear the bacteria from the stomach.

References

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of microorganisms. 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Publishers. USA. Pp.795-796.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA. Pp. 296-299.

Ryan K, Ray C.G, Ahmed N, Drew W.L and Plorde J (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Singleton P and Sainsbury D (1995). Dictionary of microbiology and molecular biology, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.