Fungal reproduction is unique and distinct from those of other microbial cells such as bacteria. Generally, fungi exhibit two modes of reproduction which are sexual and asexual reproduction. In this section, the terms conidia and spores are synonymously used but with caution since conidia are generally used to describe asexual spores of fungi. Asexual reproduction in fungi is characterized by the formation of conidia (asexual spores) by the type of cell division known as mitosis. In asexual reproduction of fungal cells, budding yeast-like structures are formed and hyphae elements undergo fragmentation or they disintegrate into several components.

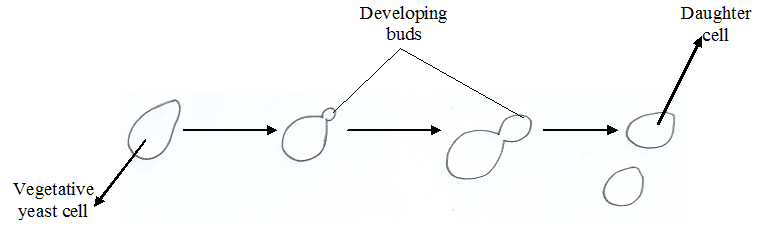

Some of the spores formed in asexual reproduction aside conidia include arthrospores, blastospores (which are formed from vegetative mother cells by budding) and sporangiospores. Most fungi especially yeast cells such as the Saccharomyces species reproduce asexually by budding, a process in which new daughter cells originate from vegetative (parent) cells as buds or outgrowth (Figure 1).

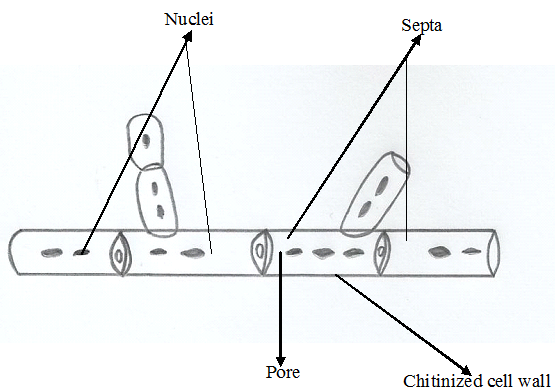

The formation of spores by fungi form the basis for the dispersal of fungi in the environment, and their formation can also be used for fungal identification in the laboratory. Generally, asexual reproduction in fungi includes the formation of conidia (asexual spores), budding of yeast cells and the fragmentation of hyphae. Fragmentation of fungal hyphae leads to the formation of arthrospores or arthroconidia (which are individual components of broken hyphae that behave like spores) and chlamydospores (which are round-thick walled and resistant hyphae cell components formed before separation of hyphae).

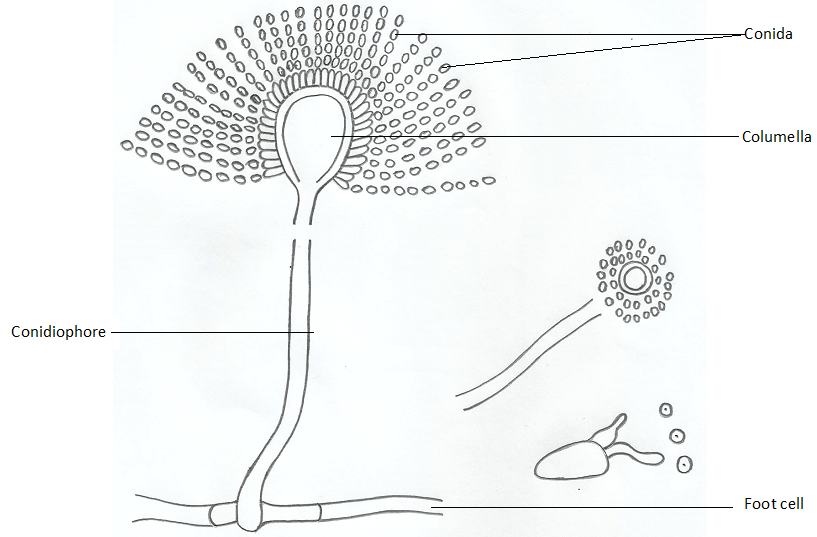

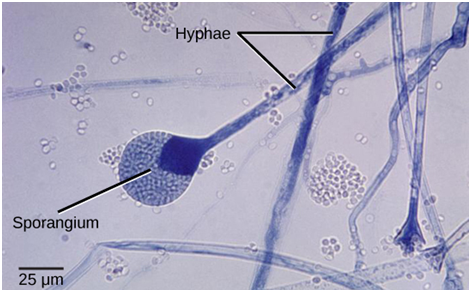

When the spores develop within a sac (i.e. sporangiophore) they are known as sporangiospores but when they develop at the side of the hyphae without enclosure in a sac they are known as conidiospores. Conidiospores develop from conidiophores. Conidia formed asexually by fungi are usually borne or encased in sac-like structures known as sporangia (singular: sporangium). The sporangia contain numerous amounts of fungal spores, and they serve as route via which spores are released and dispersed in the natural environment especially when they rupture. The conidia released in this manner are known as sporangiospores. Sporangiophore and conidiophore are the two types of fungal structures from which fungal spores are released.

In sexual reproduction the reproductive components formed are generally known as sexual spores (conidia are formed in asexual reproduction). Sexual spores are formed by meiosis. In particular, sexual spores of fungi may include zygospores (produced by zygomycetes), ascospores (produced by ascomycetes) and basidiospores (produced by basidiomycetes).Zygospores, ascospores and basidiospores are examples of spores formed by fungi during sexual reproduction.

Zygospores are sexual spores with thick walls commonly produced from a diploid zygote formed from the fusion of two haploid nuclei (known as the gametangia) or unicellular fungal gametes. They are commonly seen in the bread mould Rhizopus nigricans.Gametangia(singular: gametangium) are gamete producing structures of fungi. Ascospores are sexual spores formed by ascomycetes within a sac known as ascus. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) is a typical example of fungi that form ascospores.

Basidiospores are sexual spores formed at the end of the basidium (a club-shaped structure) by basidiomycetes. Mushrooms and Cryptococcus species are typical examples of fungi that form basidiospores. It is noteworthy that four or eight ascosporesare usually found in fungal sac-like structures known as the ascus sac. Sexual reproduction occurs when fungi mate to form sexual spores. Normally, sexual fusion occurs between gametangia, haploid gametes or hyphae; and this fusion result in the formation of diploid zygote- which go on to release sexual spores. Sexual spores formed by fungi are generally used for fungal classification as earlier said.

The other type of fungi is the deuteromycetes (e.g. Candida albicans and Coccidioidis immitis) – for which no sexual reproduction forms have yet being identified. Deuteromycetes are imperfect fungi because they lack mechanisms for sexual reproduction as against the zygomycetes, ascomycetes and basidiomycetes which all have mechanisms for sexual reproduction. However, most fungi reproduce asexually than they do sexually; and in asexual reproduction conidia or asexual spores are formed, and this reproductive element as well as sexual spores are critical for the dispersal of fungi in the natural environment (Figure 2).

Fungi can reproduce asexually by fragmentation, budding, or by spore formation. Asexual reproduction takes place in fungi by means of spore formation. Each spore formed may develop into a new individual fungus species. The spores may be produced asexually or sexually; and thus are named as either asexual spores or sexual spores depending on the type of reproduction taking place in the fungus. Asexual spores are genetically identical to the parent fungus and may be released either outside or within a special reproductive sac called a sporangium (plural: sporangia). Sporangium isa case or capsule in which spores are produced in a fungus. In a sporangium, the spores are produced within a cell and are released when the cell breaks open. Mucor species and Rhizopus species are typical examples of fungi that form spores using this process.

References

Anaissie E.J, McGinnis M.R, Pfaller M.A (2009). Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. London.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Black, J.G. (2008). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA.

Brown G.D and Netea M.G (2007). Immunology of Fungal Infections. Springer Publishers, Netherlands.

Calderone R.A and Cihlar R.L (eds). Fungal Pathogenesis: Principles and Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002.

Chakrabarti A and Slavin M.A (2011). Endemic fungal infection in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol, 9:337-344.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Germain G. St. and Summerbell R (2010). Identifying Fungi. Second edition. Star Pub Co.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Larone D.H (2011). Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. Fifth edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Levinson W (2010). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology. Twelfth edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies, USA.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Inc, USA.

Mahon C. R, Lehman D.C and Manuselis G (2011). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Fourth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

Discover more from #1 Microbiology Resource Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.