Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Aminoglycosides are antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis like the tetracyclines, and they also bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit of the bacterial ribosome. Other examples of aminoglycosides include kanamycin, tobramycin, netilmicin, spectinomycin, amikacin, neomycin and streptomycin. Streptomycin (which is naturally synthesized by the actinomycetes bacterium, Streptomyces griseus)is a unique aminoglycoside because it is used in combination with other anti-mycobacterial agents for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Streptomycin is the first aminoglycoside antibiotic to be synthesized from actinomycetes and other related soil microbes; and it was discovered by Selman Abraham in 1943.

SOURCE OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin is naturally produced by bacteria in the genus Micromonospora. However, members of the aminoglycosides can also be semi-synthesized through chemical processes especially by the chemical modification of the aminoglycoside nucleus. Aminoglycosides can also be produced by synthetic processes.

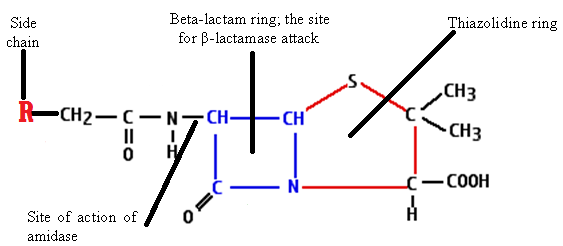

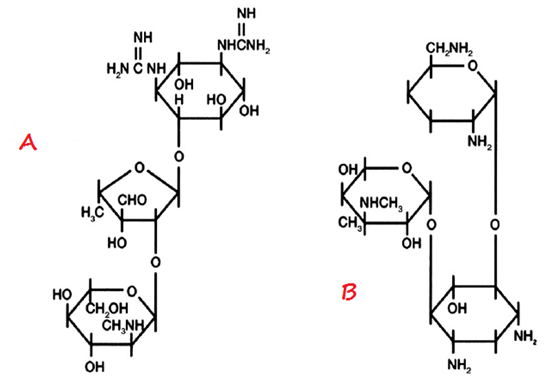

STRUCTURE OF GENTAMICIN

The structure of aminoglycosides (inclusive of gentamicin) is a 6-membered aminocyclitol nucleus (Figure 1). Aminoglycosides are mainly composed of amino sugars that are linked to each other by glycosidic bonds. The chemical modification of the aminoglycoside nucleus either by semi-synthetic or synthetic methods produces newer aminoglycosides such as kanamycin, tobramycin and amikacin amongst others.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin is generally used clinically to treat Gram-negative infections including those caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common nosocomial pathogen. But it is inactive against Neisseria species; and thus gentamicin is not used to treat infections caused by these pathogens. Aminoglycosides are used to treat bacterial infections caused by a wide variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; and some are also used to treat TB (e.g. streptomycin). Neomycin is only used for topical therapeutic applications because of its high toxicity.

SPECTRUM OF ACTIVITY OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin is a broad spectrum antibiotic and it is bacteriocidal in action. The aminoglycosides are bactericidal in action unlike the tetracyclines which are bacteriostatic in action. The binding of the aminoglycosides to the 30S ribosomal subunit of the bacterial ribosome during protein synthesis is irreversible; and this is why antibiotics in this category are bacteriocidal in action.

MECHANISM OR MODE OF ACTION OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin and other aminoglycosides bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit of the bacterial ribosomes; and their binding inhibit the synthesis of protein in the target pathogenic bacteria. The binding of the 30S ribosomal subunit leads to the misreading of the mRNA, and this interrupts translation activities during protein synthesis in the bacteria.

BACTERIAL RESISTANCE TO GENTAMICIN

The absence of a binding site on the target pathogenic bacteria due to mutation as well as the production of antibiotic-degrading enzyme can make bacteria to be resistant to the antibacterial onslaught of gentamicin and other aminoglycosides.

PHARMACOKINETICS OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin is not systemically effective when orally administered. It is poorly absorbed by the body from the intestines or GIT. Aminoglycosides are administered parenterally to treat systemic infections. They do not penetrate the CNS. Aminoglycosides show a poor degree of oral absorption and hence intravenous administration is the route usually used in patients with severe infections. Aminoglycosides are not metabolized and are essentially eliminated by glomerular filtration.

SIDE EFFECT/TOXICITY OF GENTAMICIN

Gentamicin and other aminoglycosides have some untoward effects. The prolonged clinical use of the aminoglycosides affects the kidney by impairing its biological functions; and antibiotics in this group also affect the nerves responsible for hearing. Deafness may ensue when the auditory nerves are affected. Other side effects include aplastic anaemia, ataxia, allergy and nausea and mild disturbances of the normal bacterial flora of the body.

References

Ashutosh Kar (2008). Pharmaceutical Microbiology, 1st edition. New Age International Publishers: New Delhi, India.

Axelsen P. H (2002). Essentials of Antimicrobial Pharmacology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

Balfour H. H (1999). Antiviral drugs. N Engl J Med, 340, 1255–1268.

Bean B (1992). Antiviral therapy: current concepts and practices. Clin Microbiol Rev, 5, 146–182.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Courvalin P, Leclercq R and Rice L.B (2010). Antibiogram. ESKA Publishing, ASM Press, Canada.

Denyer S.P., Hodges N.A and Gorman S.P (2004). Hugo & Russell’s Pharmaceutical Microbiology. 7th ed. Blackwell Publishing Company, USA. Pp.152-172.

Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition. Paul Singleton and Diana Sainsbury. 2006, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Canada.

Drusano G.L (2007). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antimicrobials. Clin Infect Dis, 45(suppl):89–95.

Engleberg N.C, DiRita V and Dermody T.S (2007). Schaechter’s Mechanisms of Microbial Disease. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

Finch R.G, Greenwood D, Norrby R and Whitley R (2002). Antibiotic and chemotherapy, 8th edition. Churchill Livingstone, London and Edinburg.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Gordon Y. J, Romanowski E.G and McDermitt A M (2005). A review of antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential as anti-infective drugs. Current Eye Research, 30(7): 505-515.

Hardman JG, Limbird LE, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

Joslyn, L. J. (2000). Sterilization by Heat. In S. S. Block (Ed.), Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation (5th ed., pp. 695-728). Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Katzung, B. G. (2003). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). NY, US, Lange.

Kontoyiannis D.P and Lewis R.E (2002). Antifungal drug resistance of pathogenic fungi. Lancet. 359:1135–1144.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.