Sputum culture is often recommended in the diagnoses of lower respiratory tract infection (e.g. bacterial pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis). Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) are infections/diseases that occur below the voice box (larynx) i.e. in the bronchi and trachea.

In this case, an induced or expectorated sputum specimen and not saliva is requested and obtained from the patient. The patient is asked to take a deep breath and then cough deeply to discharge what he or she coughed up into a sputum specimen collection container.

AIM: To isolate pathogenic bacteria from sputum specimens as an aid in the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections (e.g. bacterial pneumonia).

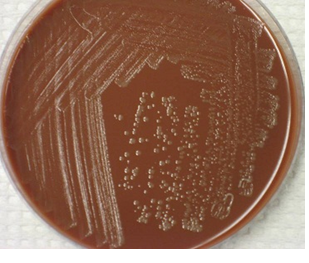

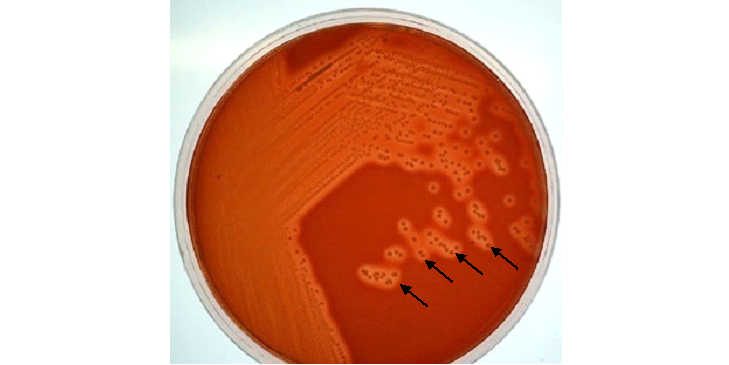

MATERIAL/APPARATUS: Sputum specimen, incubator, anaerobic jar, blood agar (BA), chocolate agar (CA), inoculating loop, grease pencil, face mask. The use of chocolate agar (CA) plates for sputum culture is important because the medium supports the growth of anaerobes and other bacteria from sputum samples including Streptococcus species, Staphylococcus species and Haemophilus species present in the sample (Figure 1).

METHOD/PROCEDURE FOR SPUTUM CULTURE

- Cover face with face mask to avoid splashing of aerosols that might emanate while working on the specimen.

- Label the BA and CA plates with the patients name and laboratory number using the grease pencil.

- Using a sterilized inoculating loop, collect a loopful of the sputum specimen.

- Inoculate it on both the CA and BA plates.

- Incubate the BA plate aerobically in the incubator at 37oC overnight.

- Incubate the CA plate anaerobically in an anaerobic jar at 37oC overnight.

- After incubation, examine both plates and look out for a significant growth of bacteria.

- Subculture the isolated organisms onto freshly prepared culture media plates (e.g. CA and BA) for the isolation of pure cultures.

- Perform biochemical tests (oxidase test, catalase test, coagulase test) to identify the isolated bacteria.

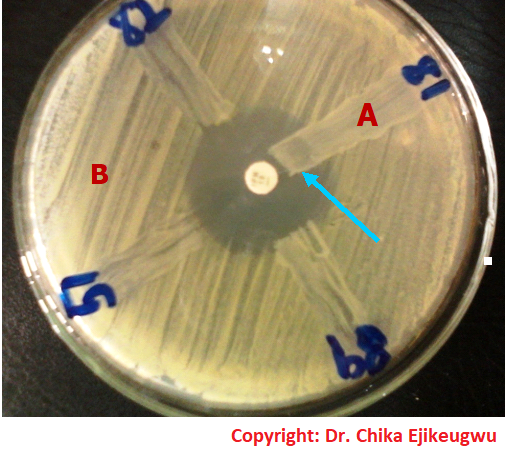

- Perform antimicrobial susceptibility test only when a significant pathogen have been isolated.

REPORTING OF THE RESULT: Look especially for a significant growth of Streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus and report any of them after proper microbiological identification of the resulting organism(s). Streptococcus species produces colonies with haemolysis on blood agar (BA) culture plates (Figure 2).

NOTE: Sputum specimens should always be collected in leak-proof specimen containers and, such specimens should be treated with caution in order to avoid cross-contamination due to infected aerosol production which may occur during handling and processing of the specimen.

The culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing of sputum specimens for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (the causative agent of tuberculosis – TB) are usually undertaken in a Tuberculosis reference center/laboratory that is normally outside the hospital environment. This is because aerosols from sputum specimens carrying M. tuberculosis can easily become airborne and cause infection.

Though some hospitals have facilities for carrying out the microscopy, culture, and sensitivity of sputum specimens suspected to contain M. tuberculosis. It is also advisable to work under a laminar flow biological safety cabinet when handling and processing sputum specimens suspected to contain M. tuberculosis in order to prevent aerosols from the specimen from coming into contact with the microbiologist.

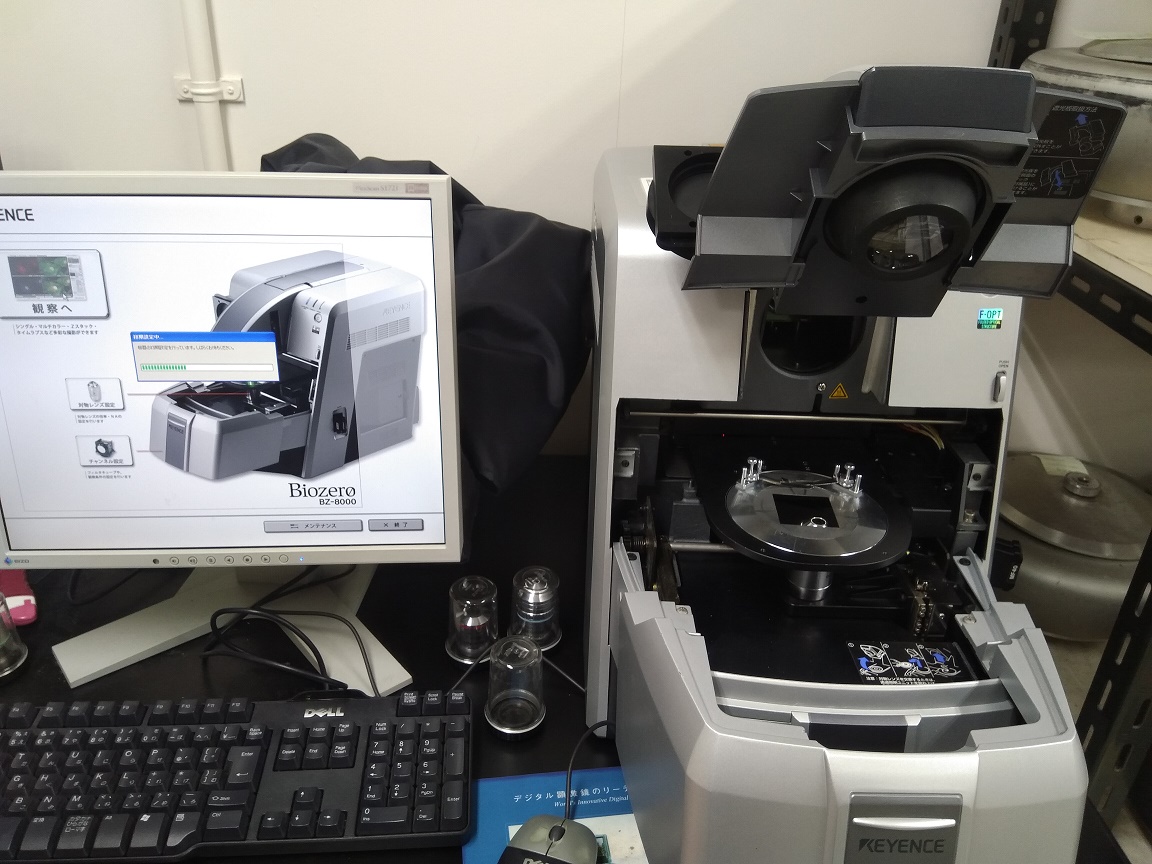

Anaerobic jar is used for the incubation of cultures in chocolate agar (CA) plates because the organisms for which this medium (CA) is meant to isolate, are anaerobes/obligate aerobes and thus require a CO2 atmosphere for growth (Figure 3). The anaerobic jar increased CO2 tension which enhances the growth of the bacteria.

References

Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. World Health Organization (WHO), 1991. Available from WHO publications, 1211 Geneva, 27-Switzerland.

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th edition. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute of Health. HHS Publication No. (CDC) 21-1112.2009.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part I. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part 2. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Collins C.H, Lyne P.M, Grange J.M and Falkinham J.O (2004). Collins and Lyne’s Microbiological Methods. Eight edition. Arnold publishers, New York, USA.

Disinfection and Sterilization. (1993). Laboratory Biosafety Manual (2nd ed., pp. 60-70). Geneva: WHO.

Garcia L.S (2010). Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Garcia L.S (2014). Clinical Laboratory Management. First edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Fleming, D. O., Richardson, J. H., Tulis, J. I. and Vesley, D. (eds) (1995). Laboratory Safety: Principles and practice. Washington DC: ASM press.

Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. (2004). Practical Microbiology. S.Chand and Company LTD, New Delhi, India.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.