Mycoses are infections caused by pathogenic fungi. And they include superficial mycoses, cutaneous mycoses, subcutaneous mycoses, systemic or deep-seated mycosis and opportunistic mycoses depending on the affected tissue or parts of the body. However, other forms of fungal infections which are not directly caused by pathogenic fungi but their toxic products and the untoward reactions which they provoke in the affected host also exist. Such clinical conditions include mycotoxicoses and fungal allergies- which are initiated following human contact with fungal spores and their toxins especially by eating food containing fungal exotoxins.

Mycotoxicoses are caused by mycotoxins (fungal exotoxins) produced by some fungal organisms that infest food especially cereals and grains. It can also occur via the inhalation of fungal spores. Human mycotoxicoses are usually caused via the consumption of foods containing mycotoxins especially those of Aspergillus flavus. A. flavus is known to produce aflatoxins in food. Mycotoxins are produced in food on which the pathogenic fungus is growing, and the consumption of such fungus-toxin infested food leads to mycotoxicoses, a clinical condition similar to the actions of bacterial toxins. Apart from causing fungal disease, mycotoxicoses causes loss of revenue and rejection of mycotoxins-infested food products as well as other economic consequences.

Fungal spores are ubiquitously found in the environment; and their inhalation by individuals who are allergic to them can cause fungal allergies or hypersensitivity reactions. Most fungal allergies are occupational diseases and they mostly occur in people who always come in contact with fungal spores such as farmers and those that work in forests or places where fungal spores are constantly retained in dust particles as aerosols. Asthma is a common example of the hypersensitivity reaction that follows the inhalation of potent fungal spores. Most fungal infections are occupationally-related i.e., they occur in people who work in a certain type of job such as construction workers, farmers, builders, forest workers and workers who are constantly exposed to dust and soil particles.

Other predisposing factors to fungal infection include the use of indwelling medical devices (e.g. urine catheters and respirators), previous organ/tissue transplant, use of immunosuppressive drugs, prolonged antibiotic usage (which depletes the normal bacterial flora that prevent the overgrowth of fungi in the body), age of the individual and other underlying disease conditions (e.g. HIV/AIDS and cancer) which impairs the host immune system. Nevertheless, there are lesser fungal infections than bacterial related diseases because of the body’s natural resistance to fungal invasion.

Most fungal infections (e.g. cryptococcosis, aspergillosis and systemic candidiasis) are opportunistic diseases and only occur in people whose immune system has been compromised. Both the innate and acquired immunity of an individual plays vital role in the prevention and containment of fungal infection in the body of a human host.

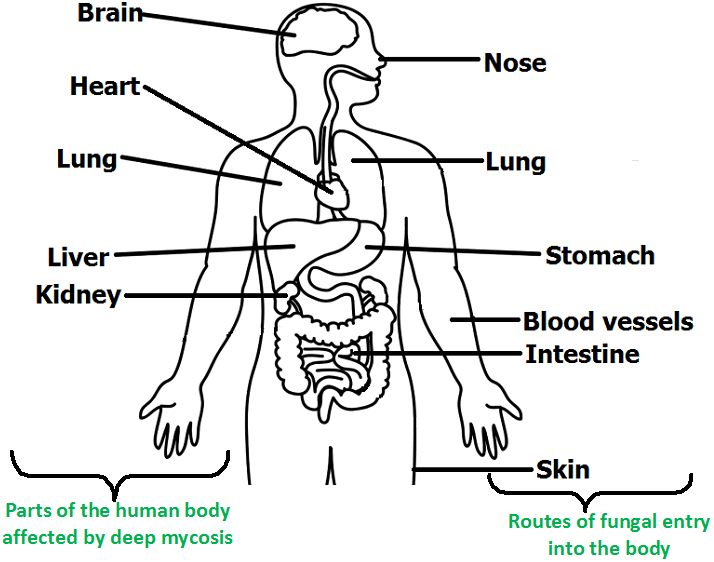

Based on their portal of entry (Figure 1), type of infected tissue and site of attack or infection, fungal mycoses are generally classified as:

Understanding MYCOSES and Their Impact

The skin is the main barrier or biological boundary line between the human body and the environment; and it protects the body from the entry of pathogenic microorganisms and from other external harmful activities. It regulates the body’s temperature; and the skin helps in the synthesis of vitamin D in man. The skin excretes nitrogenous wastes and CO2 via the excretion of sweat; and it also control environmental factors that affect deeper tissues of the body. It is tissue that covers the outside surface of the body; and the skin is the site for the synthesis of vitamin D especially when exposed to sunlight.

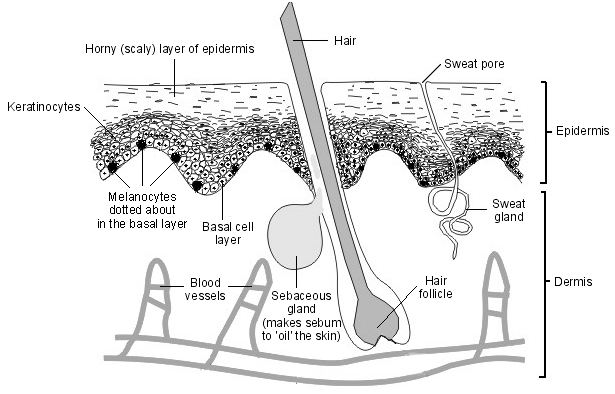

The human skin is the largest organ in the human body; and it is mainly made up of two main layers which are the epidermis and dermis aside other associated parts and cells (Figure 2).

The epidermis is the interface between the body and the environment while the dermis is the part of the skin that provides physiological support for the interface. Most fungal infections especially superficial mycoses, subcutaneous mycoses and cutaneous mycoses including some opportunistic mycoses are usually manifested clinical as dermal inflammatory response on the outermost part of the body (i.e. the skin) of the affected individual. This diagram shows the different layers of the human skin, some of which are mainly attacked by pathogenic fungi. For superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous mycoses; the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissues of the skin respectively are mainly affected.

References

Anaissie E.J, McGinnis M.R, Pfaller M.A (2009). Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. London.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Black, J.G. (2008). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA.

Brown G.D and Netea M.G (2007). Immunology of Fungal Infections. Springer Publishers, Netherlands.

Calderone R.A and Cihlar R.L (eds). Fungal Pathogenesis: Principles and Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002.

Chakrabarti A and Slavin M.A (2011). Endemic fungal infection in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol, 9:337-344.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Germain G. St. and Summerbell R (2010). Identifying Fungi. Second edition. Star Pub Co.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Larone D.H (2011). Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. Fifth edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Levinson W (2010). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology. Twelfth edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies, USA.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Inc, USA.

Mahon C. R, Lehman D.C and Manuselis G (2011). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Fourth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.