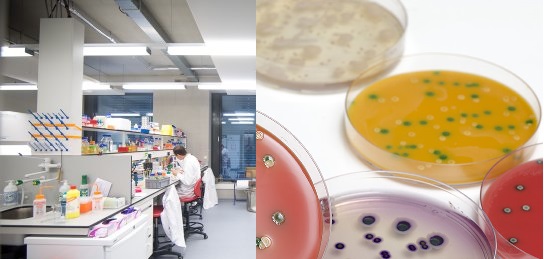

The laboratory diagnosis of fungal infection is mainly based on microscopy and cultural techniques. Several culture media exist for the selective isolation of pathogenic fungi from clinically important specimens. The choice of culture media to be used is largely dependent on the type of mycoses and the category of samples to be analyzed amongst other factors.

Specimens collected for fungal investigations in the microbiology laboratory include skin scrapings, nail clippings, hair, blood, thrush lesions from oral cavity, CSF, urine, vaginal swabs, corneal scrapings, pleural fluid, sputum bronchial washings, gastric washings, nasopharyngeal specimens, biopsy materials and abscess or pus samples.

However, the type of specimen collected from the patient is usually a reflection of the site of entry of the fungal pathogen and the ensuing mycoses in the individual. Clinical specimens for mycological investigations should be aseptically collected based on the prevailing hospitals sample collection procedures in order to get optimum result.

For skin scrapings; the site should be cleaned with 70 % alcohol to remove dirt’s or dust, oil and other contaminants using cotton wool. The disinfected site should be allowed to dry before collecting the skin scraping. Skin scrapings should be collected aseptically and in such a manner that excludes bleeding. The scrapings should be collected in a clean white paper or container.

For nails; the site should be cleaned with 70 % alcohol and allowed to dry. Nails should be aseptically clipped into clean containers and minced or crushed before inoculation onto solid media.

For hair samples; the hairs for mycological investigation should be obtained directly from the site of infection by plucking or brushing into a clean container. Woods lamp can be used to identify infected areas of the scalp where hairs should be obtained from.

For body fluids (e.g. blood, CSF, urine, abscess e.t.c); normal aseptic techniques of collecting clinical samples. Specimens for mycological investigations obtained outside the laboratory should be properly collected, packaged, labeled and transported to the laboratory for further processing to avoid the likelihood of spreading the fungal spores in the environment.

Table 1. Isolation media used to recover fungi from clinical specimens

| Media* | Description & function |

| Brain heart infusion (BHI) agar | BHI agar is composed of beef heart infusion, glucose, peptone, NaCl, distilled water, agar, calf brain infusion, and disodium phosphate as ingredients. It is used to convert diphasic or dimorphic fungi to yeast forms. BHI agar is also used for the culture of fastidious microorganisms; and it is supplemented with 5 % sheep blood in this instance. BHI agar can be prepared in Petri dishes and test tubes. It is used to recover fungi that cause systemic mycoses such as H. capsulatum and B. dermatitidis. |

| Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDA) | SDA is a general purpose medium used for the recovery of fungal organisms from clinical samples. It is composed of agar, glucose, distilled water and neopeptone. SDA is usually used to study the colonial morphology of dermatophytes (i.e. fungi that infect the skin). It is widely used for most fungal studies and it does not incorporate antibiotics. Superficial fungi such as Trichophyton species, Microsporum species and Epidermophyton species amongst others are best studied with SDA. |

| Caffeic Acid Agar (CAA) | CAA is a light sensitive medium for fungal isolation. Thus it should be protected from direct light. CAA is mainly used to recover fungi that cause opportunistic mycoses (e.g. C. neoformans). Fungal growth on CAA appears as black colonies, thus showing the production of melanin. |

| Cornmeal agar | Cornmeal agar is composed of cornmeal, agar and distilled water. It used for the recovery of fungi that causes cutaneous mycoses such as Candida and Trichophyton. When Tween 80 is added; cornmeal agar can be used for the cultivation and differentiation of Candida species usually on the basis of the mycelia features of the organism on the growth media. Cornmeal agar can also be used to induce the formation of spores or conidia in sporulating fungi. It enhances the production of chlamydospores in Candida species. |

| Cream of rice agar with Tween 80 | Cream of rice agar is composed of cream of rice (obtained as filtrate of rice boiled in water), agar, Tween 80 and distilled water. The cream of rice agar with Tween 80 is used to recover Candida species. |

| SDA with antibiotic | SDA with antibiotic media is composed of cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, agar, peptone, glucose and distilled water. Cycloheximide inhibits the growth of saprophytic fungi and some yeast while chloramphenicol inhibits the growth of bacteria including actinomycetes. SDA with antibiotic medium is different from the traditional SDA without antibiotics, and it is commercially available as Mycosel agar. They are excellent medium for the isolation of fungi from contaminated body sites or samples. SDA with antibiotic is a general purpose media for the recovery of commonly encountered fungi such as Trichophyton species and Aspergillus species amongst others. |

| Potato dextrose agar (PDA) | PDA is composed of potato infusion, glucose, agar and distilled water. Like cornmeal agar, PDA is used to induce spore formation in sporulating fungi. PDA also increases pigment production in fungi during culture. |

Most fungal specimens (e.g. skin scrapings, nail clippings and hair) are processed by direct microscopy using 10 % potassium hydroxide (KOH). This is known as the KOH mount of samples meant for fungal investigations; and the technique is a routine in most microbiology laboratory across the world. KOH (10 %) is used to dissolve the proteinaceous material of skin samples (e.g. skin scrapings) because it facilitates the detection of fungal elements from clinical specimens.

The KOH dissolves or degrades the keratinized portion of the skin or specimen so that fungal elements (e.g. spores) can be seen microscopically. Other fungal elements looked for in microscopical examination include fungal hyphae, budding yeast cells, conidia and mycelia. Wet mount preparation of the samples can also be carried out to lookout for yeast cells and other fungal structures. Another important procedure in fungal examination is the use of lactophenol cotton blue stain which stains the chitinized component of fungal cell walls so that fungal elements and/or structures can be seen.

Lactophenol cotton blue is usually used as a staining dye to increase the contrast between fungal elements and background during microscopy. Other important stains used for mycological investigations include acid fast stain (which differentiates Nocardia species from other aerobic Actinomyces); Indian ink stain (which reveal the capsules of C. neoformans in CSF specimens); fluorescent antibody stain (which is used to detect fungi in tissues or fluid specimens); Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) stain (which is used to stain the polysaccharide layer in the fungal cell wall) and Giemsa Stain (which is used for staining blood and bone marrow samples) amongst other stains or dyes. Other laboratory methods involved in the diagnosis of mycoses include serological tests (e.g. ELISA), molecular techniques (such as PCR), antigen detection tests (e.g. Latex agglutination) and skin tests which detect an individual’s delayed hypersensitivity reactions to fungal antigens in vivo.

Biochemical tests and skin tests also exist for the laboratory diagnoses of human mycoses. Fungal culture unlike bacterial culture (which is usually carried out at 37oC for 18-24 hours or overnight) is carried at room temperature (i.e. 25-28oC). The reason for this is because fungi have a longer generation time than bacteria; and thus fungal cultures are usually cultured for 48 hours or more depending on the medium and the organism being sought for. And the type of culture media to use for the isolation and identification of fungi (especially those that are of clinical significance) is dependent on the type of specimen/sample to be processed and the nutritional requirement of the fungus. Different culture media are available for the cultivation and identification of fungi in the microbiology laboratory (Table 1).

Most fungal culture media are better prepared in test tubes or slant form than in Petri dish plates. This is because tube media last longer than plate media upon usage, storage and incubation than plated media. And tube media is easy to store and there is a lesser chance of fungal spores escaping into the environment when tube culture media is used than in the plate media where fungal spore escape is likely. Tube media is less amenable to dehydration and possible environmental contamination than plate media; and their small surface area ensure maximum safety of the cultured specimen and/or organism. It is also advisable to conduct fungal experiments or culture in a biological safety cabinet or hood in order to prevent the aerosolization of fungal spores and contamination of the worker and the environment in general.

References

Anaissie E.J, McGinnis M.R, Pfaller M.A (2009). Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. London.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Black, J.G. (2008). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA.

Brown G.D and Netea M.G (2007). Immunology of Fungal Infections. Springer Publishers, Netherlands.

Calderone R.A and Cihlar R.L (eds). Fungal Pathogenesis: Principles and Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002.

Chakrabarti A and Slavin M.A (2011). Endemic fungal infection in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol, 9:337-344.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Germain G. St. and Summerbell R (2010). Identifying Fungi. Second edition. Star Pub Co.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Larone D.H (2011). Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. Fifth edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Levinson W (2010). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology. Twelfth edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies, USA.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Inc, USA.

Mahon C. R, Lehman D.C and Manuselis G (2011). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Fourth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

Discover more from #1 Microbiology Resource Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.