Beer is one of the oldest and most widely consumed alcoholic beverages globally. It is primarily produced through the microbial fermentation of wort—a sugary solution derived from malted cereal grains. This process, known as brewing, is a sophisticated biotechnological operation that relies heavily on the activity of microorganisms, especially yeasts, to convert fermentable sugars into ethanol, carbon dioxide, and various flavor compounds.

The art and science of beer production have been developed and refined over thousands of years, from ancient civilizations to the modern industrial brewing complexes. The microbiology behind brewing is intricate, encompassing microbial physiology, enzymology, fermentation biochemistry, and quality control, all of which contribute to the final characteristics of the beer.

Raw Materials in Beer Production

The principal raw materials in beer brewing include water, malted cereals (primarily barley), hops, yeasts, and adjuncts. Each of these plays a crucial role in determining the quality, flavor, and stability of the final product.

Water

Water is the largest component of beer, accounting for up to 90–95% of its volume. However, water is not just an inert medium; its chemical composition—such as pH, hardness, mineral content, and ionic balance—significantly influences the brewing process and the sensory attributes of beer. For instance, calcium ions aid in enzyme activation during mashing and improve beer clarity by precipitating unwanted proteins, while sulfate ions accentuate hop bitterness.

Given that natural water sources vary in quality and composition, brewers often treat water before use. Common treatment methods include:

- Ion exchange to remove unwanted ions like sodium or magnesium.

- De-carbonation to eliminate dissolved carbon dioxide which can affect pH and flavor.

- pH adjustment using acids (like phosphoric or lactic acid) or bases (such as calcium carbonate) to achieve optimal mash pH (typically between 5.2 and 5.6).

By controlling water chemistry, brewers can tailor the process to suit different beer styles, ranging from soft water lagers to the hard water favored in traditional IPAs.

Malt and Adjuncts

Malted barley is the cornerstone cereal grain in beer production, prized for its unique enzymatic profile and structural characteristics that make it ideally suited for brewing. The malting process involves controlled germination, where barley grains are soaked in water and allowed to sprout under carefully regulated conditions. This activates key enzymes such as amylases, proteases, and beta-glucanases, which are essential for breaking down starches and proteins during subsequent mashing. After germination, the grains undergo kilning, a drying process that halts enzymatic activity while preserving these enzymes and developing characteristic malt flavors. The resulting malted barley provides a rich source of fermentable carbohydrates—primarily maltose and other simple sugars—that serve as the primary substrate for yeast fermentation. In addition, malt contributes proteins, amino acids, and other compounds that influence the beer’s mouthfeel, color, foam stability, and overall sensory profile. The thick husk of barley also facilitates efficient filtration during brewing and protects the grain from microbial spoilage during storage.

Adjuncts are supplementary carbohydrate sources added to the mash to increase the total fermentable extract and improve the beer’s alcoholic content in a cost-effective manner. Common adjuncts include cereal grains such as corn (maize), rice, wheat, rye, oats, sorghum, and millet, as well as sugar syrups derived from sources like sugarcane or corn syrup. These adjuncts are especially valuable when malt availability is limited or when brewers seek to reduce production costs without compromising the volume of beer produced. They also allow breweries to tailor the beer’s body, flavor, and mouthfeel to specific market preferences or regional grain supplies.

However, the use of adjuncts introduces several brewing challenges. Unlike malted barley, adjuncts often lack sufficient endogenous enzymatic activity, which can result in incomplete saccharification of their starches during mashing. This can lead to lower sugar yields and inconsistent fermentation performance. Additionally, adjuncts may contribute unusual or off-flavors that affect the final beer quality, requiring careful recipe formulation and quality control. From a process standpoint, adjuncts can cause slower filtration rates and increased viscosity in the mash, complicating wort separation and extending production times.

Despite these challenges, adjuncts remain indispensable in many large-scale and commercial brewing operations. They enable brewers to produce lighter-bodied beers with a milder flavor profile or to accommodate economic and agricultural factors influencing raw material supply. Through careful balancing of malt and adjunct proportions, brewers can optimize cost, efficiency, and sensory outcomes to meet diverse consumer demands.

Hops

Hops, derived from the female cones of Humulus lupulus, are aromatic plants that impart bitterness, flavor, and aroma to beer. They also contribute to foam stability and act as a natural preservative by inhibiting microbial contamination due to their antimicrobial compounds.

Hops contain two major classes of compounds important for brewing:

- Resins: These include alpha acids (humulones) that, during wort boiling, isomerize to iso-alpha acids, providing the characteristic bitterness essential for balancing malt sweetness.

- Essential oils: These volatile compounds provide floral, citrus, piney, and spicy aromas that define beer’s bouquet and flavor profile.

The timing and method of hop addition during brewing (e.g., early boil additions, late boil, or dry hopping) profoundly affect the final sensory properties of beer.

Generally, hops are the flowering female cones of the plant Humulus lupulus, a climbing vine that belongs to the Cannabaceae family. These cones are integral to beer production, serving multiple important roles beyond merely imparting bitterness. Hops contribute significantly to the flavor, aroma, and stability of beer, making them one of the most valued ingredients in brewing. Their use dates back hundreds of years, with hop cultivation and utilization refined to optimize their impact on the final beer product.

The primary function of hops in brewing is to introduce bitterness, which balances the natural sweetness derived from malted grains. This bitterness is crucial for creating a harmonious flavor profile in beer, preventing it from being overwhelmingly sweet or cloying. The bitter compounds in hops are primarily resins, which consist mainly of alpha acids known as humulones. During the wort boiling process, these alpha acids undergo isomerization, transforming into iso-alpha acids. Iso-alpha acids are more soluble and impart the characteristic sharp bitterness associated with beer. The concentration of these acids directly influences the level of bitterness, typically measured in International Bitterness Units (IBUs).

In addition to resins, hops contain essential oils—volatile aromatic compounds responsible for the distinctive floral, citrus, piney, spicy, and herbal notes in beer. These oils contribute significantly to the beer’s bouquet and overall flavor complexity. The profile of essential oils varies among hop varieties, allowing brewers to select specific hop types to achieve desired sensory attributes.

The timing and method of adding hops during brewing critically influence the beer’s flavor and aroma. Early additions, typically at the beginning of the boil, maximize bitterness extraction, as prolonged boiling encourages the isomerization of alpha acids. Late additions, toward the end of the boil, preserve more essential oils, enhancing aroma. Dry hopping—adding hops during or after fermentation without boiling—further intensifies aromatic qualities without increasing bitterness. These techniques allow brewers to fine-tune the sensory characteristics of beer, tailoring it to particular styles and consumer preferences.

Beyond flavor and aroma, hops also contribute to foam stability, creating a desirable frothy head that enhances the beer’s visual appeal and mouthfeel. Moreover, hops possess antimicrobial properties due to their bitter acids and polyphenols, which help inhibit spoilage organisms, thus extending the beer’s shelf life and preserving its quality.

The Role of Microorganisms in Brewing

At the core of beer production is microbial fermentation, a complex biological process primarily driven by yeasts, particularly those of the genus Saccharomyces. While yeasts are the central agents responsible for converting sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide, certain bacteria also contribute to the development of unique beer styles and flavors, especially in traditional or specialty brews.

Yeasts: The Fermentative Workhorses

Yeasts are single-celled eukaryotic microorganisms belonging to the kingdom Fungi. They possess the remarkable ability to carry out anaerobic fermentation, metabolizing sugars in the absence of oxygen to produce ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide gas. This process not only generates the desired alcohol content but also influences the aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel of the final beer product through the production of various secondary metabolites, including esters, phenols, and higher alcohols.

Two primary species of yeast dominate the brewing industry:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae — commonly known as ale yeast, this species ferments at warmer temperatures (typically 15–24°C) and is characterized by its top-fermenting behavior. It tends to rise to the surface during fermentation, producing ales with a complex, fruity, and often robust flavor profile.

- Saccharomyces pastorianus (formerly Saccharomyces carlsbergensis) — used predominantly in lager brewing, this yeast ferments at cooler temperatures (around 7–13°C) and settles at the bottom of the fermenter, resulting in clean, crisp, and smooth lagers.

These yeasts primarily consume fermentable sugars present in the wort, such as glucose, maltose, and maltotriose. The yeast metabolizes these sugars through the glycolytic pathway, ultimately yielding ethanol and carbon dioxide.

However, yeasts cannot directly utilize starch molecules found in barley or other cereal grains. Prior to fermentation, starch must be broken down into simpler fermentable sugars during the mashing stage. This breakdown is facilitated by endogenous enzymes present in malted grains, notably alpha-amylase and beta-amylase, which hydrolyze starch into dextrins and fermentable sugars. This enzymatic saccharification is critical for providing yeasts with the accessible substrates needed for efficient fermentation and high-quality beer production.

Other Microbial Players in Beer Production

While yeasts of the genus Saccharomyces—especially Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus—are the primary microbes responsible for alcoholic fermentation in beer production, a variety of other microorganisms can play significant roles, either intentionally or inadvertently, influencing the fermentation process, flavor profile, and overall quality of the final product.

One notable bacterial species capable of alcoholic fermentation is Zymomonas mobilis. This bacterium metabolizes sugars via the Entner-Doudoroff pathway and produces ethanol and carbon dioxide as end products, similar to yeast fermentation. Although Z. mobilis has been studied for potential industrial brewing applications due to its high ethanol yield and rapid fermentation rates, it remains largely experimental and is not commonly used in commercial brewing operations. Challenges such as sensitivity to hop compounds and difficulty in controlling fermentation conditions have limited its widespread adoption.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Lactobacillus and Pediococcus species, are crucial in specialty beer styles, particularly sour beers. These bacteria ferment sugars into lactic acid, imparting a distinctive tartness or sourness that defines these beer varieties. Sour beers—such as Berliner Weisse, Gose, and Lambics—often rely on a controlled introduction of LAB either during or after primary fermentation. This deliberate use of bacteria requires careful management because excessive bacterial growth or contamination can lead to undesirable off-flavors or spoilage in conventional beer styles.

Wild yeasts and other microbes, including species of Brettanomyces, can also significantly impact beer flavor and quality. Brettanomyces yeasts, known for producing complex “funky” or “barnyard” aromas, are prized in some traditional and craft beer fermentations but can cause spoilage if uncontrolled. These wild microbes may enter the brewing process through inadequate sanitation or be introduced deliberately in mixed fermentations to create unique sensory profiles.

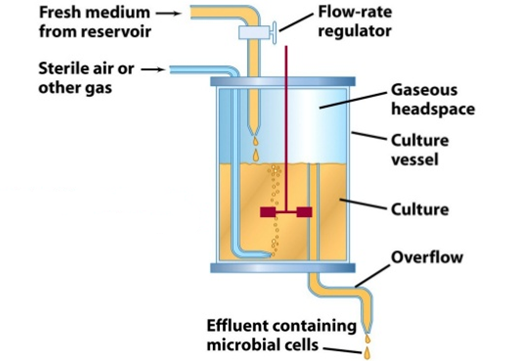

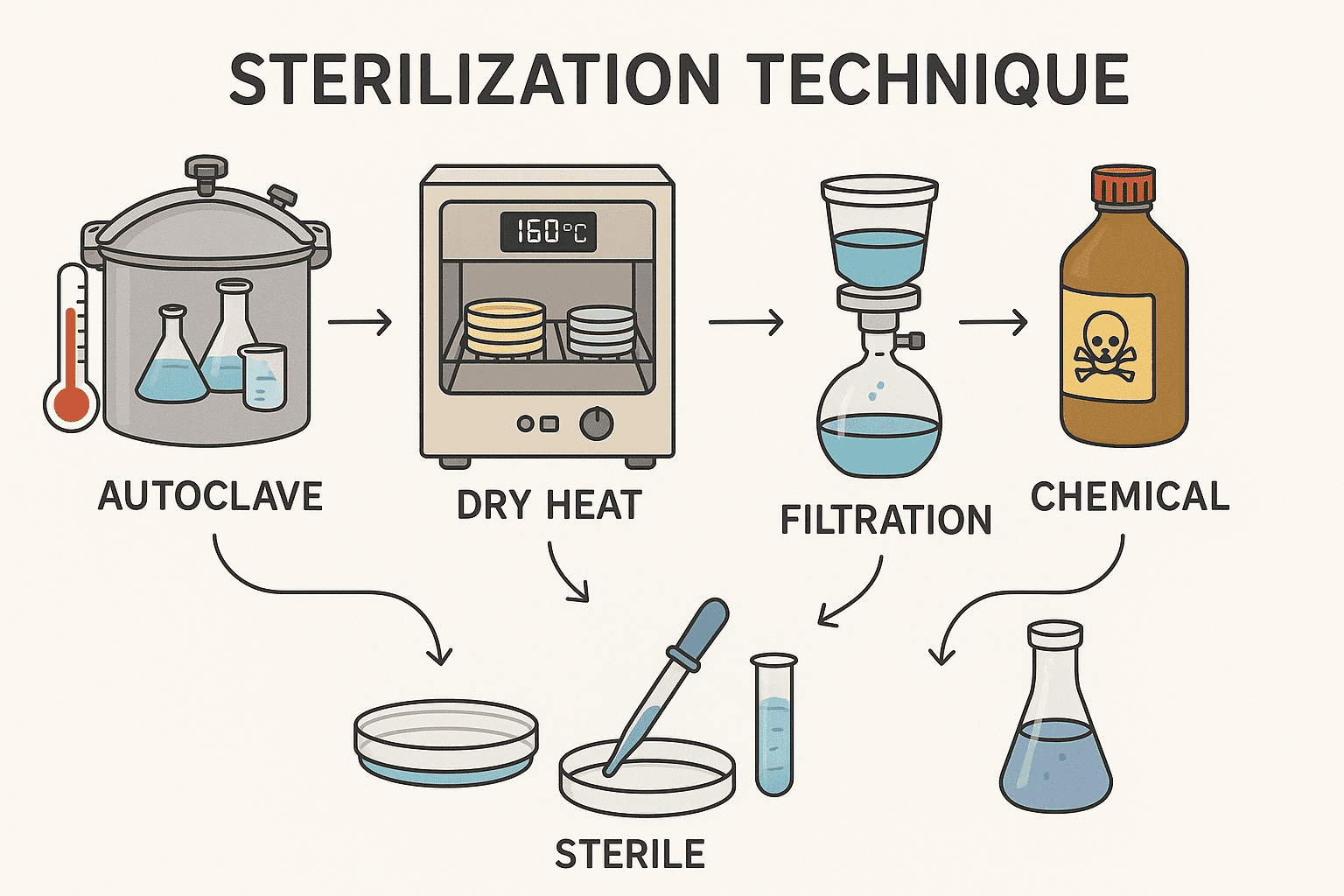

Because many non-Saccharomyces microbes can cause spoilage or inconsistent product quality, stringent control of microbial populations is essential. This involves rigorous sanitation of equipment and facilities, sterilization of raw materials and wort, and precise control of fermentation parameters such as temperature, pH, and oxygen availability. Such measures help ensure consistent product characteristics, extend shelf life, and prevent the growth of unwanted spoilage organisms.

The Brewing Process: From Grain to Glass

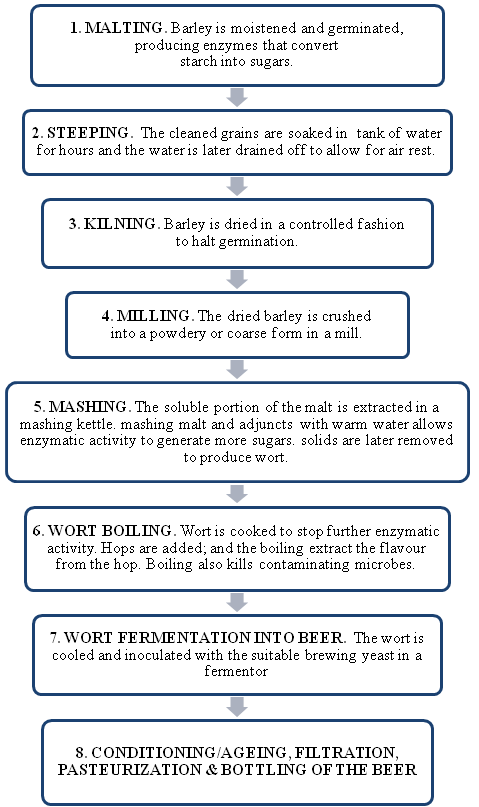

Brewing beer is a fascinating interplay of art and science that transforms simple cereal grains into one of the world’s most cherished alcoholic beverages. The brewing process involves a carefully orchestrated series of biochemical and microbiological steps, where raw materials like malted barley, water, hops, and yeast are transformed into beer. Each stage, from grain selection to packaging, profoundly influences the final product’s flavor, aroma, appearance, and stability (Figure 1). Below is a detailed overview of the brewing process, highlighting the role of enzymes, microbes, and processing techniques that convert grain into glass.

1. Malting: Awakening the Grain’s Potential

Malting is the foundational step in brewing where raw cereal grains, predominantly barley, are transformed into malt. The process begins by soaking the barley kernels in water—a step called steeping—to initiate germination. This hydration period typically lasts 2 to 3 days and activates the seed’s natural enzymes, particularly amylases and proteases, which break down complex carbohydrates (starches) and proteins stored within the grain.

As the barley germinates, these enzymes develop in abundance to prepare the seedling for growth. After several days of germination under controlled temperature and humidity, the green malt is dried in a kiln. Kilning halts further enzymatic activity, preserving the developed enzymes while also encouraging the formation of flavor and color compounds through Maillard reactions and caramelization.

The kilning temperature and duration vary depending on the desired malt type—pale malts are lightly kilned, producing mild flavors and light color, whereas specialty malts undergo higher temperatures for darker color and robust flavors like caramel, roasted, or smoky notes.

2. Milling: Preparing the Malt for Extraction

Once malted, the barley must be crushed or milled to expose the starch granules inside the endosperm while preserving the integrity of the husk. The husk plays a crucial role later during wort filtration as it forms a natural filter bed. Milling breaks the grain into grist, a mixture of coarse and fine particles. The ideal milling breaks open the starch-rich endosperm without pulverizing the husk excessively.

This step increases the surface area available for enzymatic action during mashing, facilitating more efficient starch conversion and extraction of fermentable sugars. Proper milling is essential because poorly milled malt can either clog filters or reduce starch accessibility, both detrimental to beer quality and yield.

3. Mashing: Enzymatic Transformation in Action

Mashing is where the magic of converting starch to sugar happens. The milled malt is combined with heated water in a large vessel called the mash tun, creating a thick porridge-like mixture termed the mash. Temperature control during mashing is critical, typically maintained between 62°C and 72°C, depending on the desired enzymatic activity.

At these temperatures, malt enzymes, especially alpha-amylase and beta-amylase, hydrolyze starch molecules into fermentable sugars such as maltose, glucose, and dextrins. Barley starch gelatinizes at about 52–62°C, meaning the starch granules absorb water and swell, becoming more accessible for enzymatic attack. The overlapping temperature range allows simultaneous starch gelatinization and enzymatic breakdown, enhancing efficiency.

In addition to starch breakdown, proteases partially degrade grain proteins, improving yeast nutrition and head retention in the final beer. The husks within the mash also act as a natural filter medium, facilitating wort separation in the next step.

4. Lautering and Wort Separation: Extracting the Sweet Liquid

Following mashing, the liquid portion—now called wort—is separated from the solid spent grains in a process called lautering, conducted in a vessel known as the lauter tun. During lautering, the mash bed formed by husks acts as a filter, allowing clear wort to flow out while retaining grain solids.

Wort separation is critical for beer clarity and yield. Efficient lautering depends on proper milling and the presence of husks; adjuncts like unmalted grains lacking husks can cause filtration challenges, leading to slower wort run-off and reduced efficiency.

The collected wort contains soluble sugars, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals—precisely what yeast will ferment into alcohol and flavor compounds.

5. Boiling: Sterilization, Hop Addition, and Wort Concentration

The next stage is wort boiling, typically lasting between 60 to 90 minutes. Boiling serves multiple purposes:

- Sterilization: It kills any residual microorganisms from the mash, preventing contamination.

- Enzyme Deactivation: It stops enzymatic activity, locking in the sugar profile.

- Protein Precipitation: Heat causes coagulation of proteins (known as the “hot break”), which can otherwise cause haze or off-flavors.

- Hop Addition: Hops, the flowers of the Humulus lupulus plant, are added during boiling to impart bitterness, aroma, and antimicrobial properties.

Hops contain alpha acids that isomerize during boiling, providing the characteristic bitterness balancing the beer’s sweetness. They also contain essential oils contributing to the aromatic profile and have natural antimicrobial compounds that help preserve the beer.

Boiling also evaporates water, concentrating the wort sugars, which directly affects the eventual alcohol content and mouthfeel of the beer.

6. Cooling and Aeration: Preparing for Fermentation

After boiling, the hot wort must be rapidly cooled to the appropriate temperature for yeast fermentation—typically between 10°C and 25°C depending on yeast strain and beer style. Rapid cooling reduces the risk of contamination and encourages the formation of the cold break, further precipitating proteins and polyphenols that could cause haze.

Once cooled, the wort is aerated by introducing sterile oxygen or air. Oxygen is vital for yeast during the initial growth phase because yeast cells require oxygen for synthesizing cell membranes and sterols, which promote healthy fermentation.

7. Fermentation: The Microbial Alchemy

Fermentation is the heart of brewing where yeast metabolizes wort sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, transforming sweet wort into beer. The yeast species primarily used in brewing are strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ale yeast) and Saccharomyces pastorianus (lager yeast).

During fermentation, yeast also produces a complex bouquet of flavor-active compounds including:

- Esters: Fruity, floral notes

- Phenols: Spicy, smoky characteristics

- Higher Alcohols: Contribute to body and aroma

The fermentation temperature and yeast strain largely determine the beer’s style. Ale fermentations occur at warmer temperatures (~15–24°C) and are faster, producing beers with robust and fruity flavors. Lager fermentations take place at cooler temperatures (~7–13°C) over a longer period, yielding cleaner, crisper beers.

8. Conditioning and Maturation: Flavor Refinement and Clarity

Once primary fermentation concludes, the young beer undergoes conditioning or maturation to develop its final flavor profile, clarity, and carbonation. This step may involve:

- Secondary fermentation: Sometimes in tanks or bottles, where yeast cleans up unwanted by-products.

- Cold storage (lagering): For lagers, this cold maturation smooths flavors and enhances clarity.

- Filtration: To remove yeast and particulates for visual clarity.

During conditioning, microbial activity is tightly controlled to prevent off-flavors. Some brewers add enzymes or specialized yeast strains to improve mouthfeel, foam stability, and shelf-life.

9. Packaging and Pasteurization: From Brewery to Consumer

The final step is packaging beer into bottles, cans, or kegs. Many commercial beers undergo pasteurization or sterile filtration to reduce microbial load and extend shelf life, preventing spoilage and maintaining flavor consistency.

Packaging also involves carbonation adjustment to achieve the desired level of fizz, whether naturally via residual yeast activity or by forced carbonation.

The brewing process is a remarkable blend of biology, chemistry, and engineering, relying heavily on the enzymatic breakdown of grain components and the microbial metabolism of yeast. Each step—from malting to packaging—affects the sensory qualities of beer, allowing brewers to create an almost infinite variety of styles and flavors. Understanding the science behind each stage allows brewers to optimize quality and innovate while maintaining the traditional art of brewing.

Microbial Metabolism and Biochemistry in Brewing

Alcoholic Fermentation Pathway

Yeasts metabolize glucose and other sugars via glycolysis to pyruvate. Under anaerobic or oxygen-limited conditions, pyruvate is decarboxylated to acetaldehyde, which is then reduced to ethanol by alcohol dehydrogenase.

Ethanol and carbon dioxide are the principal fermentation products, but yeast also produces secondary metabolites such as:

- Esters (e.g., isoamyl acetate) contributing fruity aromas.

- Higher alcohols (fusel alcohols) influencing flavor and mouthfeel.

- Organic acids (e.g., acetic acid) affecting beer sourness.

- Sulfur compounds which can produce desirable or undesirable aromas.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Starch

The starch contained in malt and adjuncts is hydrolyzed by alpha-amylase and beta-amylase enzymes:

- Alpha-amylase randomly cleaves internal alpha-1,4 glycosidic bonds in starch, producing dextrins and maltose.

- Beta-amylase cleaves maltose units from the non-reducing ends of starch chains.

This enzymatic action converts starch polymers into fermentable sugars usable by yeast.

The Importance of Yeast Selection and Management

Yeast plays an indispensable role in beer production, as it is the primary microorganism responsible for converting fermentable sugars in the wort into ethanol and a wide range of secondary metabolites that contribute to the aroma, flavor, and texture of the final beer product. Therefore, the selection and management of yeast strains are among the most critical decisions in industrial brewing, directly impacting fermentation kinetics, beer quality, and consistency.

Strain Selection:

The choice of yeast strain is highly deliberate and tailored to the desired beer style. Industrial brewers often rely on carefully selected or proprietary strains that have been optimized through years of research and development. These strains are chosen primarily for their:

- Alcohol tolerance: Different yeast strains can withstand varying levels of alcohol concentration before fermentation ceases or yeast viability declines. Selecting a strain with appropriate alcohol tolerance ensures complete fermentation, preventing residual sugars that could affect flavor balance or spoilage risk.

- Fermentation speed: Yeasts vary in their metabolic rate and efficiency. Faster fermenting strains shorten production times, improving brewery throughput and reducing contamination risks. Conversely, some specialty beers require slower fermentations to develop complex flavors.

- Flavor compound production: Yeasts generate an array of volatile and non-volatile compounds—esters, phenols, higher alcohols, organic acids—that shape the sensory profile of beer. For example, ale yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) often produce fruity esters, while lager yeasts (Saccharomyces pastorianus) tend to yield cleaner, crisper profiles. Selecting the right strain aligns with the target flavor profile and consumer expectations.

- Flocculation behavior: Flocculation refers to how well yeast cells clump together and settle out of suspension after fermentation. High-flocculating strains facilitate clearer beer with less downstream filtration, while low-flocculating strains remain in suspension longer, which can be desirable for certain beer styles. Managing flocculation influences product clarity and stability.

Yeast Health and Management:

Maintaining yeast vitality throughout the brewing process is essential for efficient fermentation and consistent product quality. Yeast cells that are stressed—due to poor nutrient availability, high ethanol concentration, temperature fluctuations, or microbial contamination—may produce undesirable off-flavors such as sulfur compounds, diacetyl, or acetaldehyde. Moreover, stressed yeast may cause stuck or incomplete fermentations, leaving excessive residual sugars and risking spoilage.

To avoid such issues, breweries implement rigorous yeast management practices. This includes monitoring cell viability and vitality, controlling fermentation parameters (temperature, oxygenation, nutrient supplementation), and preventing contamination by other microorganisms. Yeast cultures are often propagated in controlled conditions, and breweries may repitch yeast multiple times from previous fermentations to maintain consistent performance and reduce costs. However, repitching requires careful quality control to avoid genetic drift or contamination.

Overall, optimal yeast selection and diligent management are fundamental to producing high-quality, consistent beer, aligning the microbiological processes with the brewery’s desired flavor, efficiency, and product stability goals.

Challenges and Innovations in Brewing Microbiology

Modern brewing faces challenges such as:

- Contamination control: Preventing growth of spoilage microbes like Lactobacillus or Pediococcus which cause souring or off-flavors.

- Adjunct usage: Developing enzymatic aids or pre-treatment methods to improve saccharification and filtration when using adjuncts.

- Flavor innovation: Using novel yeast strains, wild yeasts, or controlled co-fermentation to create new beer styles.

- Sustainability: Improving water usage, energy efficiency, and waste management through microbial processes.

Conclusion

Beer production is a remarkable example of applied microbiology, where the biochemical capabilities of yeasts and the interplay of raw materials and processing conditions come together to create a diverse range of beer styles enjoyed worldwide. Understanding the microbiological and biochemical fundamentals of brewing enhances the brewer’s ability to control quality, innovate flavors, and optimize production efficiency.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.