What is Metaproteomics?

Metaproteomics refers to the large-scale characterization of the complete set of proteins (the proteome) expressed by all microorganisms in a complex microbial community within an environmental sample at a given time. It is a powerful approach within systems biology and microbial ecology that provides direct functional insights into microbial activity – distinguishing it from other omics approaches like metagenomics or metatranscriptomics.

Whereas metagenomics provides a snapshot of the genetic potential and metatranscriptomics tells us which genes are being transcribed, metaproteomics reveals which proteins are actually being synthesized and utilized by the community. This information is crucial for understanding the physiological status, metabolic functions, and interactions among microbes and between microbes and their environments. By identifying active proteins, researchers can decipher ongoing biological processes, such as nutrient cycling, pathogen defense, and antibiotic resistance in real time.

This method has found application in a variety of ecosystems, including soil, marine environments, freshwater systems, the gastrointestinal tract of animals and humans, wastewater treatment facilities, and industrial bioreactors. In each of these settings, metaproteomics enables a more functionally accurate understanding of microbial life than DNA or RNA-based approaches alone.

Functional Insight Beyond Genetic Potential

One of the key strengths of metaproteomics lies in its ability to go beyond genetic potential to offer insight into actual microbial function. For example, a metagenomic study might reveal the presence of genes involved in nitrogen fixation or antibiotic resistance, but this does not guarantee those genes are being expressed or translated into functional proteins. In contrast, metaproteomics can confirm that such genes are not just present but also actively contributing to microbial activity under specific environmental conditions.

This distinction is particularly vital in studies that explore:

- Microbial responses to environmental stressors, such as temperature shifts, drought, pollutants, or antibiotics.

- Nutrient cycling, including processes like nitrification, denitrification, carbon sequestration, methanogenesis, and phosphorus mobilization.

- Host-microbe interactions, especially in the gut microbiome, where the active production of enzymes and signaling molecules can influence immune responses and disease development.

- Ecotoxicological assessments, where the biological impact of toxic compounds on microbial metabolism can be detected via changes in protein expression patterns.

- Disease pathogenesis and immune modulation, especially in human health research where microbial proteins may serve as biomarkers or effectors in host disease.

By capturing the functional readout of a microbial community, metaproteomics allows researchers to trace biochemical pathways in action, identify stress response mechanisms, track the synthesis of key enzymes, and pinpoint metabolic bottlenecks or adaptive strategies employed by microbes in changing environments.

Protein Identification: Core Techniques

The core workflow of metaproteomics involves a combination of experimental protocols and computational analyses. These techniques must be finely tuned to accommodate the complexity and diversity of environmental samples. The standard pipeline includes:

a. Protein Extraction and Sample Preparation

Extracting proteins from complex matrices such as soil, sludge, or feces is among the most difficult steps. Environmental samples contain interfering substances (e.g., humic acids in soil) that can impede protein solubilization or downstream analysis. Strategies to improve recovery include:

- Bead-beating or mechanical disruption to lyse microbial cells.

- Use of specialized lysis buffers with surfactants or chaotropic agents.

- Application of precipitation or filtration techniques to remove inhibitors.

- Differential centrifugation to enrich microbial proteins and separate them from environmental debris.

b. Protein Digestion

Once extracted, proteins are enzymatically cleaved into smaller peptides – typically using trypsin, which cuts at specific lysine and arginine residues. This step simplifies complex protein mixtures for subsequent mass spectrometry (MS) analysis and improves peptide identification.

c. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

The digested peptides are separated using liquid chromatography (LC) based on their hydrophobicity and then analyzed via tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). MS/MS determines the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of peptides and their fragmentation patterns, which are then matched against theoretical spectra from databases to infer peptide sequences.

Advanced instrumentation such as Orbitrap, Q-TOF, and ion trap mass spectrometers are used for high-resolution, accurate mass measurements, and deep proteomic coverage.

d. Bioinformatics and Database Searching

Spectral data from MS/MS are interpreted using bioinformatics tools like MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, MetaProteomeAnalyzer, or OpenMS. A critical step is matching observed peptide spectra to predicted spectra in a protein database. However, due to the vast diversity of environmental microbes – many of which are uncultured – this process often requires:

- Custom databases, constructed from metagenomic reads or assembled genomes from the same sample.

- Functional annotations using tools such as KEGG, COG, GO, and eggNOG.

- Taxonomic assignment of proteins based on sequence homology.

This bioinformatics pipeline enables the translation of raw MS data into meaningful biological information, such as pathway activation, functional enrichment, and interspecies interactions.

Challenges and Complexity of Metaproteomics

Despite its promise, metaproteomics is not without its technical and analytical challenges. Some of the challenges include:

- Protein Recovery Issues: Environmental matrices like soil can adsorb proteins, bind strongly to organic matter, or contain inhibitors such as polyphenols and humic acids that interfere with extraction and MS detection.

- Microbial Diversity and Complexity: In diverse communities, the sheer number of proteins and their dynamic range (abundance) makes comprehensive coverage difficult. Many proteins are low-abundance and can be missed.

- Incomplete or Biased Databases: Because many environmental microbes are not yet sequenced, standard reference databases may not contain the relevant protein sequences. This leads to low identification rates and taxonomic ambiguity.

- Bioinformatics Bottlenecks: The size and complexity of metaproteomic datasets require robust computational infrastructure. Interpreting results often involves integrating functional, taxonomic, and statistical analyses, which can be resource-intensive.

- Quantitative Challenges: Unlike targeted proteomics, metaproteomics often relies on semi-quantitative measures, such as spectral counting or intensity-based label-free quantification, which can vary between samples and affect reproducibility.

Nevertheless, advances in mass spectrometry sensitivity, metagenome-informed databases, and machine learning tools for protein inference are steadily overcoming many of these obstacles.

General Workflow of a Metaproteomics Study

A typical metaproteomics experiment follows a structured workflow, designed to minimize contamination, maximize protein recovery, and ensure reliable downstream analysis.

a. Sample Collection

Samples are collected using sterile tools and stored under appropriate conditions (e.g., frozen in liquid nitrogen or preserved in RNA later for multi-omics analysis). Study design should incorporate replicates, spatial coverage, and treatment contrasts (e.g., antibiotic-treated vs. control soils).

b. Protein Extraction and Cleanup

Protocols are tailored for sample types. For instance, soil samples may require multiple cleanup steps, including acid washes and filter-based separations, to remove humic substances and enrich for microbial proteins.

c. Protein Quantification and Digestion

Protein content is measured using colorimetric assays like Bradford, BCA, or Lowry. Once quantified, proteins are digested with trypsin and desalted using solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns to purify peptides.

d. Peptide Separation and Mass Spectrometry

Peptides are separated using reverse-phase liquid chromatography and analyzed with MS/MS. Modern setups may also include data-independent acquisition (DIA) strategies, allowing deeper and more reproducible peptide coverage across samples.

e. Bioinformatics and Functional Interpretation

Protein identification is followed by taxonomic classification, functional annotation, and differential expression analysis. Pathway enrichment (e.g., via KEGG or Reactome) and statistical modeling (e.g., ANOVA, PCA) are used to extract biological insights.

Applications of Metaproteomics

Metaproteomics offers diverse applications across ecology, medicine, biotechnology, and agriculture. Its ability to provide functional fingerprints of microbial communities makes it invaluable for monitoring ecosystem health, disease progression, and biotechnological performance.

a. Soil and Environmental Microbiology

Soil metaproteomics can reveal microbial functions linked to carbon turnover, nutrient mobilization, metal resistance, and antibiotic degradation. It is also used to monitor microbial adaptation to climate change, land-use changes, or chemical stressors.

For example, during drought, metaproteomics may reveal increased expression of osmoprotectants, heat shock proteins, or reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxifiers in soil microbes.

b. Human Microbiome Studies

In clinical research, metaproteomics allows functional monitoring of gut microbiota under different dietary regimens, antibiotic treatments, or disease states such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or metabolic syndrome. Key applications include:

- Identifying biomarkers of dysbiosis.

- Mapping short-chain fatty acid production.

- Studying microbial cross-talk with the immune system.

c. Industrial and Biotechnological Applications

In bioreactors or anaerobic digesters, metaproteomics provides insights into biomass degradation, methanogenesis, and pathway bottlenecks. It helps optimize microbial performance in biofuel production, fermentation, or wastewater treatment.

d. Plant-Microbe and Host-Microbe Interactions

Metaproteomics can dissect the functional basis of plant symbioses and pathogen interactions. In rhizosphere studies, it has identified proteins linked to nitrogen fixation, plant hormone modulation, and disease resistance. Such knowledge supports the development of biostimulants or biocontrol agents.

Case Study on practical application of metaproteomics: Antibiotic Resistance in Soil Microbial Communities

In this case study which exemplifies a specific research context – exploring how antibiotic mixtures affect microbial activity in soil – metaproteomics is highly informative. It complements genetic analyses (e.g., metagenomics, qPCR) by answering some key research questions as follows:

- Are resistance genes being actively translated into proteins like beta-lactamases, efflux pumps, or ribosomal protection factors?

- How does microbial protein expression shift in response to antibiotic stress (e.g., induction of oxidative stress responses, suppression of energy metabolism)?

- Which microbial taxa are most active in expressing these functions under different antibiotic treatments?

For example, you may observe:

- An increase in proteins involved in efflux transporters in tetracycline-treated soils.

- A decrease in carbohydrate-active enzymes indicating inhibited decomposition capacity.

- A shift from proteobacteria-dominated expression profiles to actinobacteria, which are often more antibiotic-resistant.

Such findings can guide strategies for sustainable antibiotic use in agriculture and support the development of risk models for resistance evolution.

The Power of Functional Insight

Metaproteomics represents a transformative tool in microbial ecology, biotechnology, and health sciences. By going beyond gene presence to assess actual function, it enables high-resolution analysis of ecosystem services, microbial adaptation, and resilience under stress.

When integrated with metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics, metaproteomics contributes to a holistic systems biology approach, uncovering the dynamic interplay between microbes and their environments.

Though technically demanding, continued innovation in sample processing, mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics is making metaproteomics increasingly accessible, accurate, and impactful – paving the way for deeper understanding and management of microbial systems across diverse domains.

Transcriptomics

Transcriptomics is the comprehensive study of the transcriptome – the complete set of RNA transcripts produced by the genome under specific circumstances or in a particular cell. This field encompasses the analysis of messenger RNA (mRNA), non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), and other RNA species, providing insights into gene expression patterns, regulatory mechanisms, and functional genomics. By examining the transcriptome, researchers can understand how genes are turned on or off in different cells and conditions, shedding light on cellular functions and disease mechanisms.

Historical Evolution and Technological Advancements of Transcriptomics

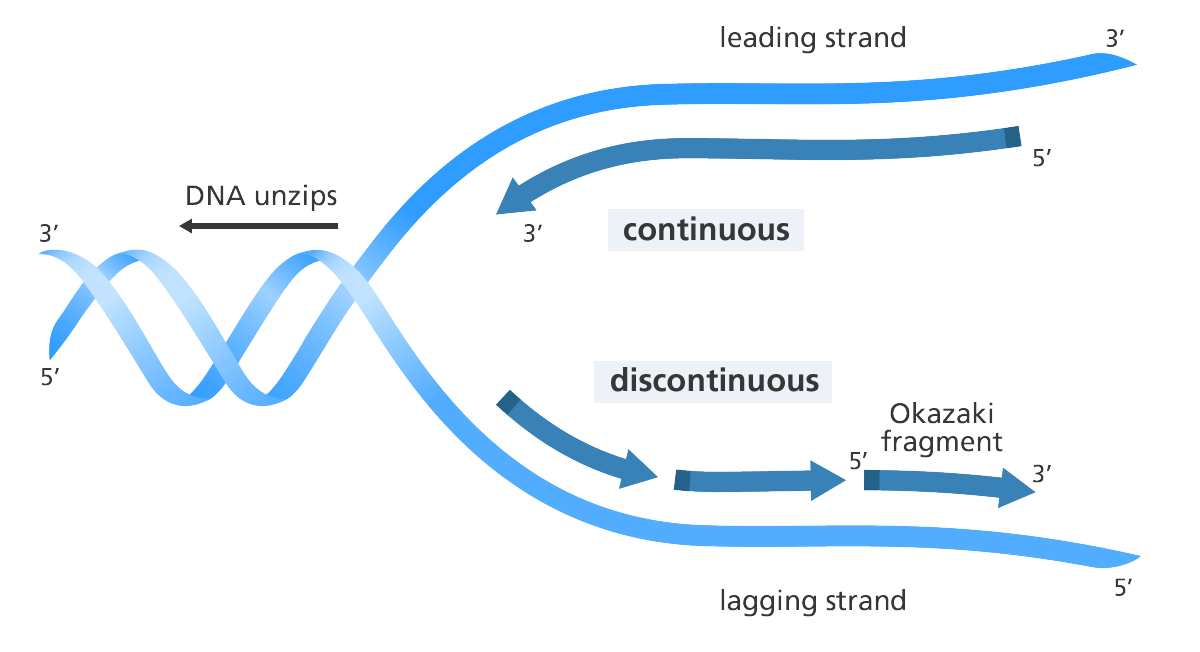

The journey of transcriptomics began with techniques like Northern blotting and real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which allowed for the detection and quantification of specific RNA molecules. The advent of microarray technology enabled the simultaneous analysis of thousands of transcripts, revolutionizing gene expression studies. However, the limitations of microarrays, such as reliance on known sequences and limited dynamic range, led to the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), an NGS-based method, provides a more comprehensive and accurate view of the transcriptome, allowing for the discovery of novel transcripts, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions.

Core Techniques in Transcriptomics

a. RNA Extraction and Quality Assessment

The first step in transcriptomic analysis involves the extraction of high-quality RNA from biological samples. Ensuring RNA integrity is crucial, as degraded RNA can compromise downstream analyses. Quality assessment is typically performed using instruments like the Agilent Bioanalyzer, which provides an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) to evaluate RNA quality.

b. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

RNA-Seq has become the gold standard for transcriptome profiling. This technique involves converting RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), fragmenting the cDNA, and sequencing the fragments using NGS platforms. RNA-Seq offers several advantages over microarrays, including the ability to detect low-abundance transcripts, novel isoforms, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

c. Microarrays

While RNA-Seq has largely supplanted microarrays, the latter still finds use in certain applications due to cost-effectiveness and established protocols. Microarrays rely on hybridization between labeled cDNA and probes on a chip, allowing for the quantification of known transcripts. However, they are limited by probe design and cannot detect novel transcripts.

d. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-Seq)

scRNA-Seq enables the analysis of gene expression at the individual cell level, uncovering cellular heterogeneity and identifying rare cell populations. This technique has been instrumental in fields like developmental biology, immunology, and cancer research, providing insights into cell differentiation pathways and tumor microenvironments.

e. Spatial Transcriptomics

Spatial transcriptomics combines gene expression data with spatial information, allowing researchers to map where specific transcripts are located within tissue sections. This approach is valuable for understanding tissue architecture, cell-cell interactions, and the spatial organization of gene expression in complex tissues.

Applications of Transcriptomics

a. Disease Diagnosis and Prognosis

Transcriptomic profiling has become a cornerstone in identifying disease biomarkers, understanding disease mechanisms, and predicting patient outcomes. For instance, in oncology, gene expression signatures derived from transcriptomic data can classify tumor subtypes, predict responses to therapy, and inform treatment decisions.

b. Drug Development and Toxicogenomics

In pharmacology, transcriptomics aids in understanding drug mechanisms of action, identifying potential off-target effects, and assessing drug-induced toxicity. By analyzing gene expression changes upon drug treatment, researchers can predict adverse effects and optimize therapeutic strategies.

c. Agricultural and Environmental Research

Transcriptomics plays a vital role in agriculture by elucidating gene expression patterns associated with plant development, stress responses, and pathogen resistance. In environmental studies, transcriptomic analyses help assess the impact of pollutants on ecosystems and understand microbial community functions.

d. Personalized Medicine

By integrating transcriptomic data with clinical information, personalized medicine aims to tailor treatments based on individual gene expression profiles. This approach enhances treatment efficacy and minimizes adverse effects, particularly in complex diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders.

Challenges in Transcriptomic Studies

a. Data Complexity and Interpretation

Transcriptomic datasets are vast and complex, requiring sophisticated bioinformatics tools for analysis and interpretation. Differentiating between biologically meaningful variations and technical noise poses a significant challenge.

b. Technical Variability

Variations in sample preparation, sequencing platforms, and data processing pipelines can introduce biases, affecting the reproducibility and comparability of results across studies.

c. Cost and Resource Requirements

Despite decreasing costs, high-throughput transcriptomic analyses remain resource-intensive, necessitating substantial computational infrastructure and expertise.

Future Perspectives

The field of transcriptomics is rapidly evolving, with emerging technologies enhancing our ability to study gene expression with greater resolution and accuracy. Advancements in long-read sequencing, integration of multi-omics data, and development of more robust analytical tools promise to further our understanding of complex biological systems and disease processes.

References

Aguiar-Pulido V, Huang W, Suarez-Ulloa V, Cickovski T, Mathee K, Narasimhan G. Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, and Metabolomics Approaches for Microbiome Analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2016 May 12;12(Suppl 1):5-16.

Hettich RL, Pan C, Chourey K, Giannone RJ. Metaproteomics: harnessing the power of high performance mass spectrometry to identify the suite of proteins that control metabolic activities in microbial communities. Anal Chem. 2013 May 7;85(9):4203-14.

Tim Van Den Bossche et al. (2025). The microbiologists guide to metaproteomics. iMeta, 2025;4:e70031.

DeLong, E. F. (Ed.). (2013). Microbial metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metaproteomics (Vol. 531, 1st ed.). Academic Press.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.