Sputum specimens are collected from patient’s suspected to have respiratory disorders example tuberculosis (TB) and pneumonia. A sterile wide – mouthed container is given to the patient to collect the sputum. Sputum passes via the pharynx and the mouth as it is being collected, and there is always a possibility of being contaminated with commensal organisms in these areas so adequate measure should be taken to obtain sputum.

During collection, it is very important that sputum and not saliva is collected. Sputum is obtained by making a very deep cough and it is best collected in the morning hours soon after the patient wakes up from sleep and before any mouth wash is undertaken. It is also advisable that the patient collects the sputum in a manner and way that it will not spread the infectious organism and contaminate the container of collection.

Stool specimens are collected from patient’s when bacterial infection of the gastrointestinal tract is suspected and when testing for feacal occult blood (FOB). They are best collected during the acute stage of diarrhea in diarrheal cases example cholera. The stool specimen should be collected in a universal container and it should not be contaminated with urine at the point of collection.

Urine specimen is collected when diagnosis point to urinary tract infections (UTIs) or renal insufficiency. The first urine passed by the patient at the beginning of the day should be collected for examination as it is this urine that is the most concentrated and therefore most suitable for microscopy and culture.

- For females: the area around the urethral opening is cleaned with clean water. The area is dried and the urine is collected with the labia of the female held apart.

- For males: the patient is told to wash his hands thoroughly and the first part of the urine is discarded before collecting the urine. Urine specimens collected in this way is called midstream urine (MSU) and it is this type of urine that is most adequate for microbiological analysis.

Urine specimens for mere microscopy can be collected in a container devoid of boric acid but that warranting both microscopy and culture should be collected in a universal container containing boric acid. Boric acid is a preservative that helps to prevent the overgrowth of any commensal organism in the specimen especially if delay in its processing is anticipated.

COLLECTION OF SEMEN (SEMINAL FLUID)

Semen specimen is collected in cases of infertility in male patients. A sterile universal container is given to the patient to take home for the collection of the semen specimen. The patient is told to abstain from sex 3 – 7 days prior to the collection and he is also told to indicate on the container the date, time, and name on the container, and to deliver the specimen to the microbiology laboratory within 30 minutes of its collection. Patients are often advised to hold the sample in between their armpits as they transport it to the laboratory after collection in order to maintain a steady temperature.

Blood specimens are collected when diagnosis points to bacteremia and septicemia. It is also collected for serological tests and detection of microfilaria. Depending on the examination required, blood specimens can be collected in either plain bottles, EDTA bottles, or Heparin bottles. Both EDTA and heparin are anticoagulants and they are responsible for separating plasma from the red cell components of blood.

EDTA means ethylenediamine tetra – acetic acid. Blood collected in plain bottles separates blood into serum and red cell components after spinning it in a centrifuge. The person that draws blood from a patient is called a phlebotomist and the unit in which this act is carried out is called phlebotomy unit. The two techniques in the collection of blood are the venous blood technique and the capillary blood technique.

In the former, blood is drawn from the vein using a needle and string; while in the latter, blood is obtained using a sterile puncture or scalpel blade to puncture or cut open the site of collection example the thumb of the hand. The venous technique is often used when a large quantity of blood is to be drawn, while the capillary blood technique is used when only a drop or a small quantity of blood is required for the analysis e.g. in some HIV screening tests.

PROCEDURE IN VENOUS BLOOD COLLECTION

- Locate a suitable vein from which the blood will be drawn, probably a vein that can be felt with the hand.

- Apply a tourniquet above the site of collection. Do not make the tourniquet to be too tight on the hand as this will cause substances like hemoglobin, plasma, protein, and calcium to concentrate at the point of collection.

- Disinfect the area with 70 % of ethanol using a sterile cotton wool and allow to dry.

- Insert the needle with its bevel (orifice) directed upwards into the vein.

- Pull the plunger of the string to obtain the required amount of blood needed.

- Release the tourniquet before removing the needle from the vein. Dispense the blood into the appropriate container and forward for analysis.

- Then apply a sterile dry cotton wool to the site of collection until the bleeding stops.

COLLECTION OF THROAT SWAB SAMPLES

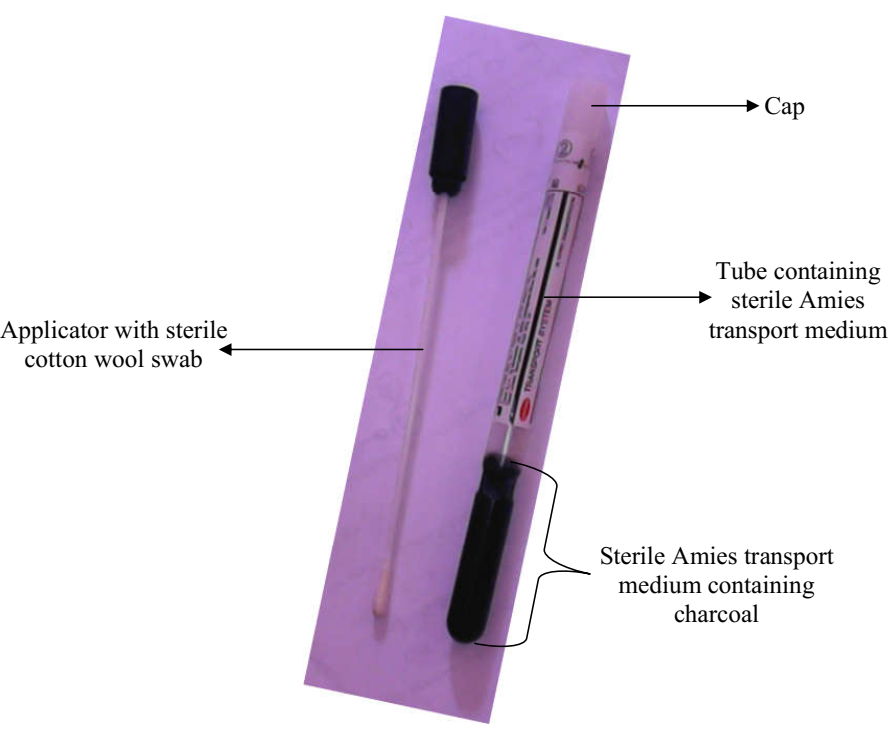

Throat swab is usually collected when infection of the upper respiratory tract (e.g. sore throat) is suspected. It should be collected by an experienced nurse or medical officer, and the patient should be advised to deviate from taking any antibiotic or mouth wash prior to collection of the specimen. In a good lighted room, use the handle of a spoon to press down the tongue.

Look out for inflammation, and the presence of pus, exudates or membranes. Swab the affected area using a sterile cotton swab stick. Ensure that the swab is not contaminated with saliva as you carry out the procedure. Return the swab stick to its sterile container and send the specimen to the microbiology laboratory immediately.

The major task of the clinical microbiologist is to isolate and identify disease causing agents (pathogens) from clinical specimens of patients so that appropriate steps can be taken by the physician towards the management and treatment of patients. The clinical microbiology laboratories must be able to grow, isolate, and identify most routinely encountered pathogens within 48 hours of sampling.

The isolation and growth of pathogens from host tissue is indeed an important step in defining the cause of many infectious diseases; and after a pathogen is successively isolated and identified and tested for antimicrobial susceptibility, a specific treatment plan can be arranged for the affected patient (s). The purpose of the clinical microbiology laboratory is to provide the physician with information concerning the presence or absence of microbes that may be involved in the infectious disease process of a patient.

The standard operating procedures (SOPs) for different microbiology laboratories differ. Therefore, it is advisable and very important that readers of this work stick to and follow the SOPs of the laboratory where they found themselves as this work is not exhaustive but only a guide, and a very good one at that.

REFERENCES

Atlas R.M (2010). Handbook of Microbiological Media. Fourth edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Balows A, Hausler W, Herrmann K.L, Isenberg H.D and Shadomy H.J (1991). Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Black, J.G. (2008). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition. Paul Singleton and Diana Sainsbury. 2006, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Canada.

Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. (2004). Practical Microbiology. S.Chand and Company LTD, New Delhi, India.

Garcia L.S (2010). Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Garcia L.S (2014). Clinical Laboratory Management. First edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Inc, USA.

Mahon C. R, Lehman D.C and Manuselis G (2011). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Fourth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA. Pp. 296-299.

Ryan K, Ray C.G, Ahmed N, Drew W.L and Plorde J (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.