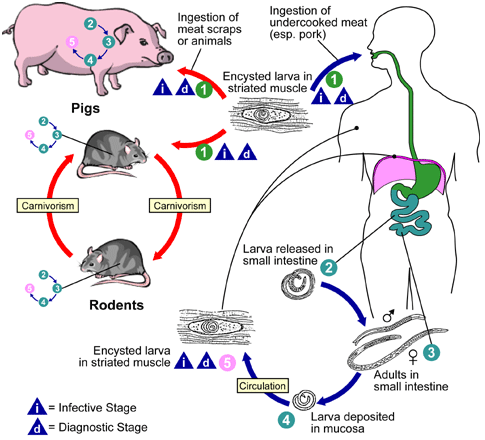

Trichinellosis or trichinosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by tissue nematodes or roundworms after the ingestion of contaminated meat (e.g. undercooked or raw pork meat) containing the encysted larva of the parasite. The disease is also common in pigs, rats and other domestic and wild animals; and the causative agent of trichinosis is known to inhabit the intestinal mucosa of carnivorous animals such as lion, bears and wild pigs.

Trichinosis is a widespread zoonotic parasitic disease in flesh-eating animals throughout the world, and pigs are mostly affected amongst the other domestic animals because swine normally feed on rats or trash that contain meat harbouring the infective encysted larva of the parasite. Ingestion of contaminated undercooked or raw pork meat is the only route via which human infection occurs; and trichinellosis is not a communicable parasitic disease.

Trichinosis is widespread in nature and it occurs in parts in Africa, Asia, South America and Europe. Trichinellosis is caused by Trichina worms in the genus Trichinella; and the main causative agent of the disease is T. spiralis. T. spiralis is made up of three subspecies including T. s. spiralis, T. s. nelsoni and T. s. native.T. spiralis morphologically exist in the cyst and larval form. Encysted larva is the main infective form of the parasite.

Vector, reservoir and habitat

The definitive and intermediate hosts of T. spiralis include pigs, humans, rats and other wild and domestic animals. Humans however are the dead-end host for T. spiralis because the disease and/or parasite cannot be transferred from one human host to another even though the disease is acquired via eating animal flesh containing encysted larva of the worm.

Clinical signs and symptoms of Trichinella infection

Human infections with T. spiralis are usually subclinical i.e. without appreciable clinical symptoms. However, vomiting, abdominal cramp, nausea, diarrhea, fever, swelling of the face and headache are some of the symptoms of trichinellosis. Myocarditis and heart failure are some complications associated with T. spiralis infection in man; and this is usually due to the migration of the worms in the body.

Pathogenesis of Trichinella infection

Human infection with T. spiralis occurs after the ingestion of undercooked or raw pork meat containing the encysted larva of the parasite (Figure 1). After ingestion, encysted larva reaches the small intestine (especially the duodenal and jejuna parts) where they develop into adult male and female worms. Mature female worms produce larva which reach the skeletal or striated muscles of the body via the bloodstream of their hosts.

Larva can also be found in the CNS and heart; and their presence is usually followed by marked inflammatory reactions that spur the host’s immune response into action. Consumption of undercooked or raw pork meat containing the encysted larva of T. spiralis is the only process by which human infection occurs, but trichinellosis is now on the decline due to the freezing and proper cooking of pork meat.

Laboratory diagnosis of Trichinella infection

Trichinellosis is diagnosed in the laboratory by detecting the encysted larva of T. spiralis in striated or skeletal muscle tissues of infected persons. Normally, muscle biopsies collected from infected patients after a short local anesthesia reveal the larva of the parasite. Serodiagnosis which detects antibodies to T. spiralis in serum also exists, and a marked rise in the eosinophilia level of infected persons also gives suspicion of the disease.

Treatment, control and prevention of Trichinella infection

Trichinosis can be treated with mebendazole but infected persons with severe complications such as myocarditis, pulmonary infection and oedematous lesions are normally treated with corticosteroids. Corticosteroids or steroids are believed to ease the pain caused by the parasite in the infected muscles. Trichinellosis is a preventable zoonotic parasitic disease; and the infection can best be prevented by proper cooking of meat especially pork meat before consumption.

References

Aschengrau A and Seage G.R (2013). Essentials of Epidemiology in Public Health. Third edition. Jones and Bartleh Learning,

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Chiodini P.L., Moody A.H., Manser D.W (2001). Atlas of medical helminthology and protozoology. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition. Paul Singleton and Diana Sainsbury. 2006, John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Canada.

Ghosh S (2013). Paniker’s Textbook of Medical Parasitology. Seventh edition. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers,

Gillespie S.H and Pearson R.D (2001). Principles and Practice of Clinical Parasitology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. West Sussex, England.

Gordis L (2013). Epidemiology. Fifth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

John D and Petri W.A Jr (2013). Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. Ninth edition.

Kumar V, Abbas A.K, Fausto N and Aster A (2009). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th edition. W.B. Saunders Co, USA.

Lee JW (2005). Public health is a social issue. Lancet. 365:1005-6.

Leventhal R and Cheadle R.F (2013). Medical Parasitology. Fifth edition. F.A. Davis Publishers,

Lucas A.O and Gilles H.M (2003). Short Textbook of Public Health Medicine for the tropics. Fourth edition. Hodder Arnold Publication, UK.

MacMahon B., Trichopoulos D (1996). Epidemiology Principles and Methods. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. USA.

Mandell G.L., Bennett J.E and Dolin R (2000). Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Molyneux, D.H., D.R. Hopkins, and N. Zagaria (2004) Disease eradication, elimination and control: the need for accurate and consistent usage. Trends Parasitol, 20(8):347-51.

Nelson K.E and Williams C (2013). Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory and Practice. Third edition. Jones and Bartleh Learning

Roberts L, Janovy J (Jr) and Nadler S (2012). Foundations of Parasitology. Ninth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Schneider M.J (2011). Introduction to Public Health. Third edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, Massachusetts, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.