Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive, capsular, non-motile and catalase-negative cocci that are usually lancet (bullet) shaped. S. pneumoniae also occurs in pairs (diplococci) or in chains (streptococci); and they are haemolytic in nature and inhibited by optochin. A member of the normal flora of the human upper respiratory tract system, S. pneumoniae (commonly referred to as pneumococcus), is notorious in causing a range of infections in human beings. It is the most common cause of community acquired pneumonia in humans.

Other infections in which S. pneumoniae is implicated are osteomyelitis, abscesses, otitis media, meningitis, bacteraemia, peritonitis, endocarditis and cellulitis. Virulent strains of S. pneumoniae have surface capsules composed mainly of high-molecular monosaccharides and oligosaccharides that interfere with phagocytosis. The upper respiratory tract of humans is the main reservoir of pneumococci, and they can be spread to susceptible host via respiratory droplets through this route.

Pneumococci colonize the upper respiratory tract without causing any disease, but infection ensues following weakened immune system and poor state of health. Pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae is most prevalent amongst certain individuals with some predisposing factors such as prior viral infection of the respiratory tract, history of alcoholism, drug intoxication, injury to the respiratory tract, heart failure, diabetes and old age amongst others.

PATHOGENESIS OF STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

Pneumonia (reduced function of the lungs) is a lung disease that is caused by certain pathogenic bacteria species including S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus). Other bacteria that cause human pneumonia are Staphylococci, Haemophilus, Pseudomonas, Mycoplasma and Chlamydia. Non-bacterial causes of pneumonia are some species of viruses, fungi and protozoa. The virulence of infection caused by S. pneumoniae is usually determined by some virulent factors such as pili, capsules, cell wall surface proteins (teichoic acid and peptidoglycan), haemolysins, hydrogen peroxides and autolysins.

The onset of pneumonia in humans starts following the aspiration of respiratory secretions that contains virulent strains of S. pneumoniae.Upon invasion and possible colonization of the upper respiratory tract where they normally inhabit, S. pneumoniae reaches the lower respiratory tract where they attack the alveolar cells and produce a variety of lung diseases. S. pneumoniae multiplies rapidly in the alveolar spaces, and produce inflammatory cells which fills the alveoli and/or lungs.

Systemic infections due to pneumococcus occur when S. pneumoniae reaches the body’s blood circulation via the lymphatic vessels of the lungs. S. pneumoniae can reach other sites of the body such as the middle ear, heart and meninges via the respiratory tract and produce further clinical complications. Fever, chills, chest pain, difficulty in breathing and expectoration of sputum usually accompanied with blood (i.e. rusty coloured blood) are some of the clinical signs and symptoms associated with pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae.

Bronchial pneumonia and lobar pneumonia are the two types of pneumonia caused by pneumococcus in humans. Bronchial pneumonia is common in old people, young children and infants while lobar pneumonia is commonly experienced by young adults. Uncapsulated strains of pneumococcus are generally avirulent, and are not capable of producing pneumonia in humans. Only the capsulated S. pneumoniae strains actually produce the clinical episodes of the disease, and this is because capsulated pneumococci have polysaccharide capsules that protect them from phagocytosis.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

The laboratory diagnosis of pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae is mainly based on the identification and isolation of the pathogen from patient’s specimens via microscopy and culture techniques. Sputum, CSF, exudates and blood specimens are usually the main samples collected when pneumococcal pneumonia is suspected. Gram stained smear of sputum samples reveals Gram-positive lancet (bullet) shaped diplococci.

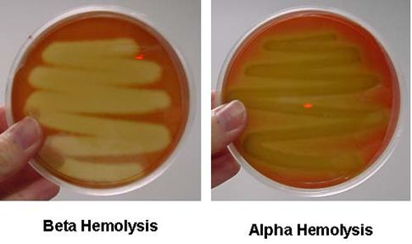

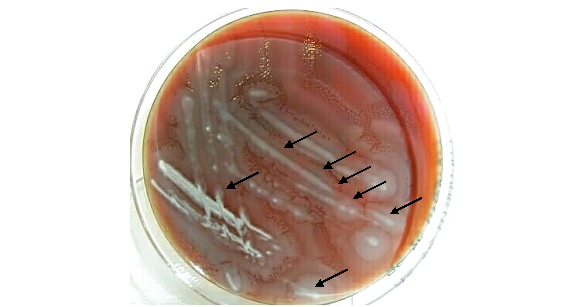

S. pneumoniae is a fastidious bacterium, and they grow best in culture media supplemented with horse, rabbit or human blood and incubated in 5% carbon dioxide. On blood agar, S. pneumoniae produce mucoid or translucent colonies that are alpha haemolytic; and pneumococcus is optochin sensitive and soluble to bile salts. Biochemically, pneumococcus ferment glucose to produce lactic acid. Serologically, S. pneumoniae is positive to the quellung reaction test also known as the swelling reaction.

In quellung reaction test which is used to determine the polysaccharide capsule of S. pneumoniae, the capsules of pneumococcus swells markedly when the pathogen is mixed with certain specific antiserum and then examined microscopically at 1000X for capsular swelling. Quellung reaction test is usually used for the rapid detection of pneumococcus from cultures and sputum samples in the microbiology laboratory.

IMMUNITY TO STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

Immunity against pneumococcus is strain-type specific. There are about 90 different serotypes or antigenic variants of pneumococcus. Protection against pneumococcal pneumonia or any of the pathogenic strains of the pathogen is usually based on intact phagocytic function of the host’s immune system, and on antibody production against the capsular polysaccharide of S. pneumoniae.

Antibody production by the host enhances phagocytosis or opsonization of the invading bacteria. However, a lasting natural form of immunity after prior infection cannot be established, which is why pneumococcal pneumonia can occur throughout a person’s lifetime especially in young adults, the elderly and people with a debilitated immunity.

TREATMENT OF STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

Pneumonia caused by pneumococcus is stopped abruptly when the right antimicrobial agents are administered early. Penicillins V & G, vancomycin, cephalosporins, macrolides and quinolones are some of the drug classes used to treat and manage pneumococcal pneumonia. Some strains of pneumococcus may be resistant to some first-line antibiotics such as penicillins, thus antibiotic therapy should be guided by the results of susceptibility studies.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE INFECTION

Pneumococcal pneumonia is typically an endemic respiratory infection that occurs occasionally in human populations (who are the main reservoirs of the causative agent). S. pneumoniae is a transient member of the human normal flora; and the organism colonizes the upper respiratory tract (nasopharynx) of both children and healthy adults who harbour pneumococcus asymptomatically. Mortality due to pneumococcal pneumonia is usually high in the elderly, people with impaired natural resistance against the pathogen (e.g. sickle cell patients), and in the debilitated or immunocompromised individuals.

Such individuals should be properly vaccinated against the disease and its causative agent since immunization confers a lasting form of protection. The prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia is largely based on immunization using pneumococcal vaccine and the effective treatment of affected individuals. About 90 virulent strains of S. pneumoniae are known, and there exist effective vaccines (Pneumovax 23) for the prevention of a handful of the pneumococcal strains that cause pneumonia in humans (especially the elderly and debilitated people).

A seven-valent conjugate vaccine for immunization in children under the age of two years is also available and effective. People at high risk of having respiratory tract infections, those with weakened immunity, the elderly and healthcare personnel’s should be vaccinated against pneumococcus. The vaccine (Pneumovax 23) is believed to help increase host phagocytic action against the capsulated pneumococcus in vivo. People should avoid factors that can predispose them to the disease (as earlier stated in this textbook), and treatment should be started early once pneumococcal pneumonia is suspected.

References

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of microorganisms. 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Publishers. USA. Pp.795-796.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA. Pp. 296-299.

Ryan K, Ray C.G, Ahmed N, Drew W.L and Plorde J (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Singleton P and Sainsbury D (1995). Dictionary of microbiology and molecular biology, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.