Stool culture is demanded in the bacteriology laboratory as method for detecting and diagnosing enteric bacterial infections (i.e. infections caused by pathogens in the Enterobacteriaceae family e.g. Salmonella species and Shigella species) that lead to enteric fever, diarrhea and dysentery. Stool culture can also be requested when patients present with other gastrointestinal infections such as peptic ulcer.

AIM: To isolate and identify pathogenic bacteria from feacal specimen culture as an aid in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal infections.

MATERIAL/APPARATUS: Stool specimen, salmonella-shigella agar (SSA), MacConkey agar (MCA), xylose – lysine deoxycholate (XLA), Bunsen burner, inoculating loop, incubator, grease pencil.

SSA = Salmonella-Shigellaagar

MCA = MacConkey agar

METHOD/PROCEDURE FOR STOOL CULTURE

- Label the SSA and MCA plates using a grease pencil.

- Using a sterilized inoculating loop, collect a speck or loopful of the stool specimen.

- Inoculate it on the SSA and MCA plates respectively.

Note: The inoculating loop should be flamed or sterilized intermittently as the streaking continues.

- Incubate both plates in the incubator at 37oC overnight.

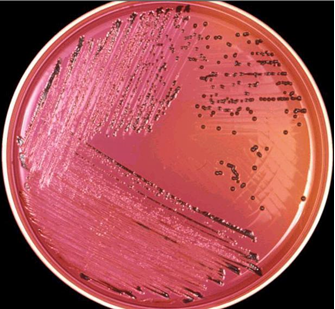

- After incubation, bring out the plates and look for colonies of Shigella or Salmonella on the SSA plate, and colonies of Escherichia coli and other lactose fermenting organisms on the MCA plate. E. coli for example produces pinkish colonies on MacConkey agar plates (Figure 1). Salmonella produces blackish colonies on XLA due to the production of hydrogen sulphide (Figure 2).

- Subculture suspect colonies of bacteria to a new SSA and MCA plates in order to obtain a pure culture of the isolated organism – which is the basis for any meaningful identification of a bacterium in the microbiology laboratory. The initial culturing and subculturing of the isolated bacteria should be followed aseptically to avoid contamination.

- Perform biochemical testing on the isolated pure culture organisms in order to identify the isolated organism(s) by giving it a name. The biochemical tests to perform may include: urease test, indole test, citrate test, and sugar fermentation test using triple sugar iron agar.

Note: The type of biochemical test used depends on the suspect organisms present in the sample; and usually on the particulate organism(s) the researcher is looking for.

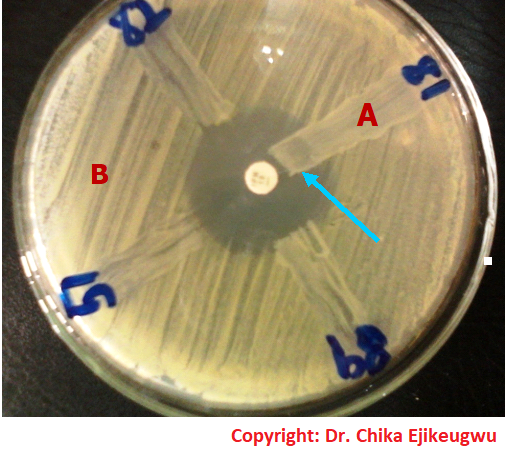

- Perform antimicrobial susceptibility test only when a pathogen is successfully isolated and identified. Susceptibility testing helps the physician to select the right antibiotics for treatment.

NOTE: If the stool specimen is very thick and obtaining a loopful of it will be difficult, make a thick suspension of it in about 1 ml of sterile peptone water. Take a loopful from the stool specimen in the peptone water tube and perform your inoculation from it.

SSA plate is for the isolation of Salmonellaand Shigella. Both are non – lactose fermenters (NLF), and appear as a pale or colourless colonies on the SSA plate. Xylose – lysine deoxycholate (XLD) agar can also be used in place of SSA as both perform almost the same function.

MCA PLATE is for the isolation of lactose fermenters (LF) like E. coli. E. coli and other lactose fermenting organisms appear as pinkish colonies on the MCA plate (Figure 2).

REPORTING OF THE RESULT: Examine the culture plates, and report the cultures based on the identified bacteria found o the plate after incubation. The culture of a stool specimen, and subsequent isolation and identification of any pathogen present may take about 3 – 4 days before any final conclusions can be reached. Depending on whether any meaningful isolation and identification was made or not, stool culture results can be reported in any of the following ways:

- Cultures yield no significant growth.

- Cultures yield no bacteria growth.

- Cultures yield bacteria growth (e.g. Enteropathogenic E. coli. Before you can confidently say that cultures yield a particular organism, you must have carried out all the necessary biochemical tests and serotyping required for identifying a pathogenic bacterium present in the sample.

It is advisable to stick to and operate by the standard operating procedures (SOP’s) of the laboratory in which you are doing the work, as the SOP’s for laboratories may vary. Also, familiarization with the different types of bacteria implicated in causing intestinal infections and how they can be identified and differentiated from each other is an advantage. Nevertheless, experience in stool culture is also a prerequisite to identifying the causative agent(s) present in the stool sample.

References

Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. World Health Organization (WHO), 1991. Available from WHO publications, 1211 Geneva, 27-Switzerland.

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th edition. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute of Health. HHS Publication No. (CDC) 21-1112.2009.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part I. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part 2. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Collins C.H, Lyne P.M, Grange J.M and Falkinham J.O (2004). Collins and Lyne’s Microbiological Methods. Eight edition. Arnold publishers, New York, USA.

Disinfection and Sterilization. (1993). Laboratory Biosafety Manual (2nd ed., pp. 60-70). Geneva: WHO.

Garcia L.S (2010). Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Garcia L.S (2014). Clinical Laboratory Management. First edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Fleming, D. O., Richardson, J. H., Tulis, J. I. and Vesley, D. (eds) (1995). Laboratory Safety: Principles and practice. Washington DC: ASM press.

Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. (2004). Practical Microbiology. S.Chand and Company LTD, New Delhi, India.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.