Sterility is central and important for the success of any industrial fermentation process. Industrial microbiology operates at the interface of microbial physiology, biochemical engineering, and large-scale manufacturing. Whether producing antibiotics, amino acids, enzymes, vaccines, biofuels, organic acids, or recombinant proteins, the fermentation process is fundamentally a controlled ecological system. A single production organism often a bacterium, yeast, filamentous fungus, or mammalian cell line is cultivated under defined physicochemical conditions to maximize yield and productivity. Sterility is not merely a hygienic ideal; it is a process-critical parameter. Contamination by microorganisms’ compromises:

- Product yield (through substrate competition)

- Product quality (e.g., degradation, altered glycosylation patterns)

- Process kinetics (e.g., altered oxygen demand)

- Downstream processing efficiency

- Regulatory compliance (particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing)

In industrial fermenters ranging from 10 L pilot units to 200,000 L production-scale bioreactors, contamination events can result in catastrophic batch failure, huge economic or financial losses, and reputational damage for the industry or company involved. Therefore, sterilization techniques constitute the foundational control barrier in fermentation process design.

Fundamentals of Sterilization

Sterilization versus Disinfection

- Sterilization is the complete elimination or destruction of all forms of microbial life, including vegetative cells, spores, viruses, and in some contexts, mycoplasma and bacteriophages.

- Disinfection is the reduction of microbial load to acceptable levels. It does not necessarily eliminate spores.

Industrial fermentation requires sterilization not disinfection of critical process streams and contact surfaces in order to produce contaminant-free products.

Bioburden and Sterility Assurance Level (SAL)

In pharmaceutical-grade production, sterility is validated statistically. The Sterility Assurance Level (SAL) is typically 10⁻⁶, indicating a one in one million probability of a non-sterile unit.

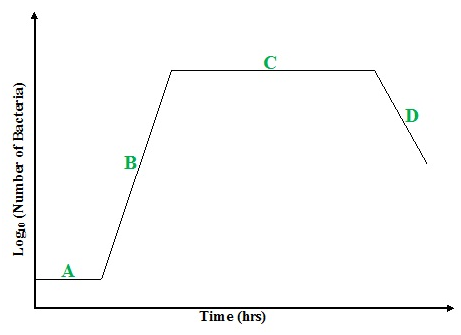

Microbial inactivation kinetics are often described using:

- D-value (decimal reduction time): Time required at a specific condition to reduce microbial population by 90% (1 log).

- Z-value: Temperature change required to alter the D-value by one log.

- F₀ value: Equivalent sterilization time at 121°C (steam), integrating temperature-time lethality.

These parameters guide thermal sterilization validation in fermenter systems.

Thermal Sterilization

Thermal sterilization is the most extensively utilized sterilization strategy in industrial microbiology because it offers predictable lethality, ease of validation, and compatibility with the aqueous matrices that dominate fermentation media. In large-scale bioprocessing, most substrates, buffers, and culture broths are water-based, making heat transfer highly efficient. Moreover, thermal systems can be engineered to industrial scales with precise control over temperature, pressure, and exposure time, allowing robust achievement of defined sterility assurance levels (SAL), typically 10⁻⁶ for pharmaceutical applications.

Thermal sterilization processes are grounded in microbial death kinetics. Microbial inactivation under heat exposure follows logarithmic reduction behavior, characterized by D-values (decimal reduction time) and Z-values (temperature sensitivity coefficient). These parameters allow engineers to calculate the F₀ value – the equivalent sterilization exposure at 121°C ensuring consistent lethality across varying cycle profiles. Because thermal energy penetrates uniformly in fluids and metal vessels, it remains the most dependable method for sterilizing fermenters, piping systems, and culture media at scale.

Moist Heat Sterilization (Steam Sterilization)

Moist heat sterilization, typically using saturated steam under pressure, is the gold standard in industrial fermentation facilities. Steam is preferred over dry heat because of its superior heat transfer efficiency and enhanced microbial lethality at lower temperatures and shorter exposure times.

Mechanism of Action

Moist heat destroys microorganisms primarily through irreversible damage to essential cellular macromolecules:

Denaturation of proteins

Heat disrupts hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds that maintain tertiary and quaternary protein structure. Enzymes lose catalytic function when their three-dimensional conformations collapse. Because microbial survival depends on metabolic enzymes, structural proteins, and regulatory proteins, widespread denaturation results in rapid loss of viability.

Disruption of nucleic acids

Elevated temperatures induce strand separation and depurination in DNA. RNA molecules are also destabilized. Although DNA damage alone may not immediately kill vegetative cells, combined macromolecular injury overwhelms cellular repair systems, particularly in spores once their protective structures are compromised.

Membrane destabilization

Phospholipid bilayers become increasingly fluid at high temperatures. Steam exposure compromises membrane integrity, increasing permeability and leading to leakage of intracellular contents. Loss of membrane function disrupts proton motive force, transport systems, and osmotic balance.

Coagulation of cellular macromolecules

Moist heat causes coagulative changes in cytoplasmic components. Unlike dry heat, which causes oxidative damage, steam promotes hydrolytic and coagulative processes that are more lethal at lower temperatures.

The critical advantage of steam lies in its latent heat of vaporization. When saturated steam contacts a cooler surface, it condenses into water, releasing a large quantity of energy instantaneously. This phase change ensures highly efficient and uniform heat delivery to equipment surfaces and media. Proper steam sterilization depends on complete air removal; trapped air reduces heat transfer efficiency and can create cold spots.

Autoclaving

Autoclaves are pressurized vessels designed to expose materials to saturated steam at controlled temperatures and pressures. Autoclaving is a sterilization process that uses saturated steam under pressure to destroy all forms of microbial life—including vegetative cells, bacterial spores, fungi, and viruses—by exposing materials to elevated temperatures for a defined period of time. It is a moist heat sterilization method in which items are placed in a sealed pressure vessel (an autoclave) and subjected to steam at temperatures above the normal boiling point of water, typically 121°C at ~15 psi (1 bar) over atmospheric pressure, for a validated holding time sufficient to achieve the required sterility assurance level (SAL).

Standard operating conditions of autoclaving include:

- 121°C for 15-30 minutes, typically at 15 psi (approximately 1 bar over atmospheric pressure), suitable for routine sterilization of culture media and laboratory equipment.

- 134°C for 3-5 minutes, used in high-pressure cycles requiring rapid turnover and enhanced sporicidal activity.

Principles of autoclaving

Autoclaving relies on two physical principles:

- Pressurization of steam

Increasing pressure raises the boiling point of water, allowing steam temperatures to exceed 100°C. - Latent heat transfer during condensation

When saturated steam contacts a cooler surface, it condenses into liquid water and releases a large amount of latent heat. This rapid energy transfer efficiently denatures microbial proteins and destroys cellular structures.

Mechanism of Microbial Inactivation using Autoclave

Autoclaving causes irreversible microbial death through:

- Protein denaturation

- Membrane disruption

- Enzyme inactivation

- Coagulation of cytoplasmic components

- Structural damage to spores

Because moisture enhances heat penetration and protein coagulation, steam sterilization is more efficient than dry heat at comparable temperatures.

The selection of cycle parameters depends on the initial bioburden, volume of material, thermal resistance of target microorganisms, and heat penetration characteristics.

In industrial microbiology, autoclaves are primarily used for:

- Small-scale fermenters and pilot vessels

- Media bottles and preparation tanks

- Glassware and stainless-steel components

- Instruments, fittings, and sampling devices

Cycle validation involves biological indicators containing heat-resistant spores (commonly Geobacillus species) to confirm adequate lethality.

However, autoclaving is impractical for large production bioreactors due to size constraints and integration within fixed piping networks. Instead, industrial-scale fermenters are sterilized using Sterilization-in-Place (SIP) systems, which introduce steam directly into the vessel and associated process lines without dismantling the equipment. This integrated approach ensures comprehensive sterilization while maintaining system integrity and minimizing contamination risk during handling. Moist heat sterilization especially via steam and autoclaving – remains the foundational sterilization strategy in industrial microbiology because of its mechanistic reliability, scalability, and regulatory acceptability.

Sterilization-In-Place (SIP)

Sterilization-In-Place (SIP) is a critical unit operation in industrial fermentation systems, designed to sterilize the entire closed process assembly without dismantling equipment. It involves the controlled introduction of saturated steam into the bioreactor, associated piping, valves, probes, filters, and transfer lines to achieve validated sterilization conditions throughout the system. SIP is typically integrated with automated process control systems to regulate temperature, pressure, and exposure time, ensuring uniform heat distribution and elimination of cold spots. By avoiding disassembly, SIP minimizes contamination risk, reduces downtime, enhances operational efficiency, and ensures compliance with stringent GMP sterility assurance requirements.

Scope of SIP

SIP systems sterilize:

- Fermenter vessel

- Agitator shaft and seals

- Baffles

- Sampling ports

- Probes (pH, DO)

- Media lines

- Air lines

- Harvest lines

Process Sequence in Steam Sterilization (SIP Systems)

Pre-cleaning (CIP – Cleaning-in-Place): Pre-cleaning is a prerequisite for effective sterilization. Cleaning-in-Place (CIP) removes residual biomass, proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and mineral deposits that could insulate microorganisms from thermal exposure. Alkaline and acid washes are circulated through the vessel and piping under turbulent flow conditions. Effective soil removal prevents biofilm persistence and ensures direct steam contact with all internal surfaces during sterilization.

Steam Introduction into Vessel: After cleaning, saturated steam is introduced into the fermenter and associated piping network through dedicated steam ports. Air removal is critical at this stage because trapped air reduces heat transfer efficiency and creates cold spots. Steam displaces air via pressure gradients and venting valves. Uniform distribution is ensured through engineered steam traps, pressure regulators, and condensate management systems.

Controlled Temperature Ramp-Up: The temperature ramp-up phase gradually increases internal vessel temperature to the validated sterilization setpoint. Controlled heating prevents thermal shock to vessel components, sensors, and seals. Multiple thermocouples monitor temperature distribution to verify uniform heating. The ramp rate must be optimized to avoid incomplete air displacement while achieving rapid attainment of sterilization conditions across all internal surfaces.

Hold Phase (e.g., 121–125°C for 30–60 minutes): During the hold phase, the system maintains a constant sterilization temperature for a validated duration sufficient to achieve the required sterility assurance level. Lethality calculations (F₀ values) confirm adequate microbial inactivation. Temperature uniformity is continuously monitored to detect deviations. This phase ensures destruction of resistant spores and validates process reproducibility under worst-case loading conditions.

Condensate Drainage: As steam condenses on cooler surfaces, liquid condensate accumulates within the vessel and piping. Efficient drainage through steam traps and sloped piping prevents pooling, which could create temperature gradients or recontamination risks. Continuous condensate removal maintains effective steam contact and consistent heat transfer. Proper drainage design eliminates dead legs and stagnant zones within the system.

Controlled Cooling Under Sterile Air Pressure: Following sterilization, the vessel is cooled gradually while maintaining positive pressure using sterile-filtered air. Positive pressure prevents ingress of non-sterile external air during cooling-induced vacuum formation. Cooling rates are controlled to protect mechanical seals, gaskets, and instrumentation. Sterile air filtration systems ensure microbiological integrity is maintained until inoculation or process initiation.

Critical Parameters of SIP

- Uniform steam distribution

- Removal of cold spots

- Adequate condensate drainage

- Pressure control (to prevent contamination ingress)

- Validation via thermocouples and biological indicators (e.g., Geobacillus stearothermophilus spores)

SIP reduces contamination risk from manual handling and is essential for GMP-compliant facilities.

Continuous Thermal Sterilization of Media

In high-throughput production (e.g., citric acid or amino acids), batch sterilization is inefficient. Continuous sterilizers are used.

High-Temperature Short-Time (HTST) Systems

- Rapid heating (e.g., 140–150°C for 30–60 seconds)

- Rapid cooling before fermentation

Advantages of HTST

- Reduced nutrient degradation

- Lower caramelization risk (important for sugar-rich media)

- Higher throughput

Heat exchangers (plate or tubular) are central components.

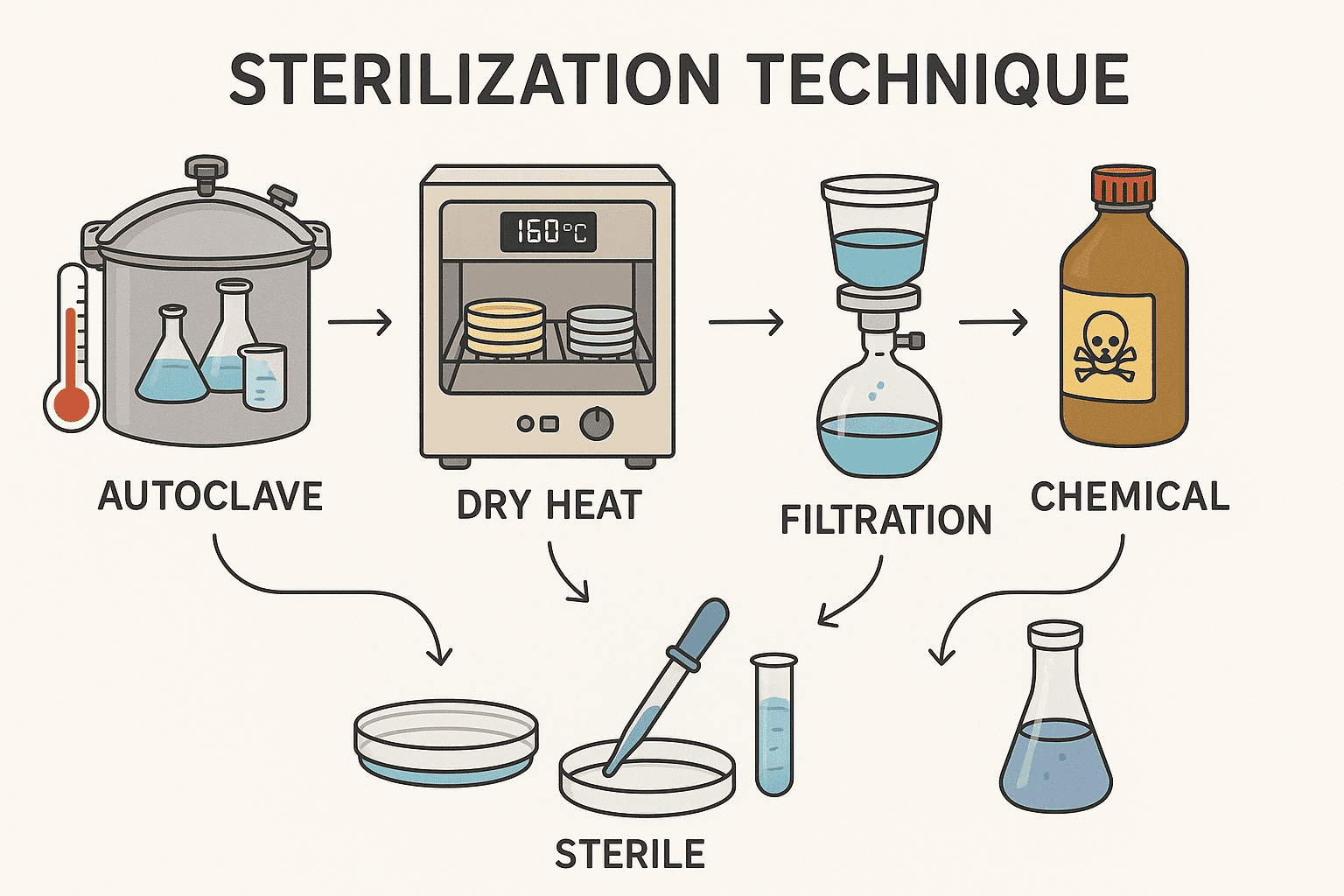

Dry Heat Sterilization

Dry heat is used for:

- Glassware

- Metal components

- Oils and powders

Typical conditions of dry heat sterilization is: 160–180°C for 2–4 hours

Mechanism of dry heat sterilization involves oxidative damage and protein denaturation. It is less efficient than moist heat due to lower heat transfer.

Filtration Sterilization

Heat-sensitive components such as vitamins, antibiotics, serum, and recombinant proteins -require non-thermal sterilization.

Membrane Filtration

In membrane filtration, microorganisms are physically removed by size exclusion. The standard pore size of membranes for sterilization: 0.22 µm

Membrane filtration is used for:

- Media supplements

- Antibiotics

- Inoculum transfer

- Sterile air supply

Filter Materials used for membrane sterilization include:

- Polyethersulfone (PES)

- Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)

- Cellulose acetate

- PTFE (for gases)

Air Sterilization in Fermentation

Aerobic fermentation requires massive air volumes. Contaminated air is a major contamination vector. Aerobic fermentation processes may require several volumes of air per volume of culture per minute (vvm), making air one of the largest material inputs. Because air contains dust, fungal spores, bacteria, and bacteriophages, inadequate air sterilization can rapidly compromise culture purity. Therefore, engineered air handling systems are designed to deliver sterile, particulate-free airflow under controlled pressure and humidity conditions.

HEPA Filters

High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters remove ≥99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm. High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters remove ≥99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm through mechanisms including interception, impaction, and diffusion. Although 0.3 µm represents the most penetrating particle size, HEPA filters are even more efficient for smaller particles due to Brownian motion effects. Integrity testing, such as aerosol challenge tests, ensures filter performance before installation and during scheduled maintenance cycles.

HEPA is installed in:

Installed in:

- Air inlet systems

- Cleanrooms

- Laminar flow hoods

Air inlet systems: In fermentation facilities, HEPA filters are positioned downstream of compressors and dryers to ensure sterile process air before entering the bioreactor. They are often protected by prefilters to extend lifespan. Proper housing design prevents bypass leakage, and pressure differentials across the filter are continuously monitored to detect clogging or failure.

Cleanrooms: HEPA filtration maintains classified cleanroom environments by reducing airborne particulates to defined ISO standards. In aseptic manufacturing zones, laminar airflow patterns minimize turbulence and particle accumulation. Continuous environmental monitoring verifies compliance with regulatory particle count thresholds and microbial limits during operation.

Laminar flow hoods: Laminar airflow cabinets use HEPA-filtered air delivered in a unidirectional flow to create localized sterile working zones. These systems protect open manipulations such as inoculations or sampling. Uniform airflow velocity reduces cross-contamination risk by sweeping particulates away from critical process areas.

Hydrophobic Vent Filters

Hydrophobic vent filters prevent contamination through exhaust lines while allowing gas exchange. They are installed on fermenter exhaust lines to prevent microbial ingress while allowing pressure equalization and gas exchange. Constructed from PTFE or similar materials, they repel liquid moisture, preventing blockage from condensate. Regular integrity testing ensures they maintain sterility during long fermentation runs.

Air systems often combine:

- Prefilters

- Steam sterilization

- HEPA filtration

Prefilters

Prefilters remove larger particulates before air reaches HEPA units, protecting fine filtration media from rapid fouling. This staged filtration approach reduces operational costs and maintains airflow efficiency. Prefilters are routinely replaced according to pressure-drop specifications.

Steam sterilization

Certain air distribution lines and housings are sterilized in place using steam to eliminate residual microorganisms before fermentation begins. Steam exposure complements filtration by sterilizing internal pipe surfaces, ensuring no contamination persists upstream of HEPA units.

HEPA filtration

Final-stage HEPA filtration ensures that air entering the fermenter meets sterility specifications. Redundant filter configurations may be used in critical applications to increase reliability. Continuous monitoring of airflow and pressure differentials supports preventive maintenance strategies.

Chemical Sterilization

Chemical sterilants are used when heat is impractical or materials are heat-labile. They are employed when materials are heat-sensitive or incompatible with steam sterilization. These agents inactivate microorganisms through chemical reactions that damage proteins, nucleic acids, and membranes. Chemical sterilization is particularly relevant for single-use components, enclosed isolator systems, and complex equipment assemblies.

Ethylene Oxide (EtO)

- Alkylates DNA and proteins

- Used for single-use systems and plastic components

- Requires aeration phase to remove residues

Ethylene oxide is a gaseous sterilant that alkylates amino, hydroxyl, and carboxyl groups in DNA and proteins, disrupting replication and metabolic activity. It penetrates porous materials effectively, making it suitable for packaged medical and bioprocess devices. However, its flammability and carcinogenic classification require strict handling controls and validated aeration procedures.

Limitations of ethylene oxide:

Toxicity

Ethylene oxide residues can pose health risks to personnel and may remain adsorbed in polymers if aeration is inadequate. Occupational exposure limits are tightly regulated. Comprehensive monitoring and ventilation systems are required to ensure workplace safety and regulatory compliance.

Long cycle times

EtO sterilization cycles can extend over many hours, including conditioning, gas exposure, and prolonged aeration phases. This reduces throughput compared to steam sterilization. Extended processing time may limit operational flexibility in high-demand manufacturing environments.

Environmental concerns

Ethylene oxide emissions are regulated due to environmental and public health impacts. Facilities must implement emission control technologies such as catalytic oxidizers. Increasing regulatory scrutiny has led some manufacturers to seek alternative sterilization technologies.

Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂)

Used in:

- Vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) systems

- Isolators

- Aseptic filling lines

Vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) systems

VHP systems disperse hydrogen peroxide vapor uniformly within enclosed spaces, achieving rapid surface sterilization. Controlled humidity and concentration ensure optimal sporicidal activity. Automated cycles allow repeatable decontamination of isolators and equipment chambers.

Isolators

In aseptic processing, isolators use VHP to maintain sterile internal environments separated from operators. This reduces reliance on cleanroom classifications and enhances contamination control during critical manipulations such as filling operations.

Aseptic filling lines

Hydrogen peroxide vapor sterilizes filling enclosures, conveyor systems, and packaging materials prior to product contact. Rapid decomposition into water and oxygen minimizes residual contamination risk after aeration.

Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide generates reactive oxygen species that oxidize membrane lipids, denature proteins, and damage nucleic acids. Oxidative stress overwhelms cellular defense systems, leading to rapid microbial death, including spores at appropriate concentrations.

Advantages of hydrogen peroxide

Rapid

Hydrogen peroxide systems operate in relatively short cycles compared to EtO, improving operational efficiency. Automated dosing and aeration control enhance reproducibility and minimize downtime between production runs.

Leaves minimal residue (water and oxygen)

Following decomposition, hydrogen peroxide breaks down into environmentally benign byproducts, reducing concerns about toxic residues. This makes it attractive for applications requiring minimal post-sterilization cleanup.

Peracetic Acid

Peracetic acid is a strong oxidizing agent used for surface sterilization and CIP enhancement in bioprocess systems. It is effective against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and spores, even in the presence of organic matter. Its efficacy against biofilms makes it valuable in preventing persistent contamination within stainless-steel piping networks.

Used for:

- Surface sterilization

- CIP enhancement

They are effective against spores and biofilms.

Radiation Sterilization

Radiation sterilization uses high-energy electromagnetic waves or particles to disrupt microbial DNA. It is particularly useful for pre-packaged, single-use bioprocess components that cannot tolerate heat or chemical exposure.

Gamma Radiation

- Uses Cobalt-60

- Deep penetration

- Suitable for single-use bags and tubing

Mechanism of gamma radiation

- DNA strand breaks via ionizing radiation

Gamma radiation is used extensively in single-use bioreactor technology.

Gamma radiation sterilization uses radioisotopes such as Cobalt-60 to emit high-energy photons. These photons penetrate deeply into packaged materials, ensuring uniform sterilization throughout dense loads. Precise dose mapping validates that minimum required radiation levels are achieved across all product surfaces.

Mechanism of gamma radiation

Ionizing radiation causes double-strand DNA breaks and generates free radicals that damage cellular components. The cumulative molecular damage prevents replication and leads to irreversible microbial death.

Gamma sterilization is extensively used for single-use bioreactor bags, tubing assemblies, and connectors in disposable bioprocess platforms.

Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation

- Limited penetration

- Surface sterilization

- Air and water treatment systems

UV-C (254 nm) disrupts nucleic acids via thymine dimer formation.

Ultraviolet radiation, particularly UV-C at 254 nm, provides surface-level sterilization by inducing thymine dimer formation in DNA. Its limited penetration restricts use to exposed surfaces, air streams, and thin liquid films. UV systems are commonly installed in air ducts and water purification units to reduce microbial loads continuously.

Cleaning-In-Place (CIP) as a Pre-Sterilization Prerequisite

Cleaning-In-Place (CIP) is a validated, automated cleaning process used in industrial fermentation systems to remove residual soils from internal equipment surfaces without dismantling the system. Effective sterilization is contingent upon prior cleaning because residual organic and inorganic matter can insulate microorganisms from thermal or chemical exposure. Deposits on vessel walls, agitators, piping, and heat exchangers may create microenvironments where steam penetration is impaired, thereby compromising sterility assurance. Consequently, CIP is not merely a hygiene step but a critical control measure within GMP-compliant bioprocess operations. CIP systems are engineered to ensure turbulent flow, appropriate chemical concentration, controlled temperature, and defined contact time. Spray balls or rotary jet heads distribute cleaning solutions uniformly across internal surfaces. Flow velocity is carefully calibrated to achieve mechanical shear forces sufficient to detach adherent residues and disrupt developing biofilms.

CIP Sequence

Pre-rinse (water)

The initial water rinse removes gross debris and soluble residues from previous fermentation batches. This step reduces organic load and prevents excessive neutralization of subsequent cleaning agents. Warm water may be used to improve solubility of sugars and proteins.

Alkaline wash (e.g., NaOH)

An alkaline solution, typically sodium hydroxide, solubilizes proteins, hydrolyzes fats, and saponifies lipids. Elevated temperature enhances cleaning efficiency. Alkaline detergents may include surfactants to improve wetting and penetration into surface irregularities.

Intermediate rinse

This rinse removes residual alkali and dissolved contaminants, preventing chemical carryover into the acid wash stage. Conductivity monitoring is often used to confirm complete removal of cleaning chemicals.

Acid wash (e.g., nitric acid)

Acid solutions dissolve mineral scales, precipitated salts, and metal oxides that accumulate during fermentation. This step restores stainless steel passivation and removes inorganic deposits that alkaline solutions cannot address.

Final rinse (WFI or purified water)

A final rinse using Water for Injection (WFI) or purified water eliminates residual chemicals and ensures surfaces are free from contaminants prior to sterilization.

CIP effectively removes biofilms, protein deposits, and carbohydrate residues. Without thorough cleaning, microorganisms embedded within organic matrices may be shielded from steam contact, resulting in incomplete sterilization and potential batch failure.

Integration into GMP and Regulatory Frameworks

Industrial fermentation especially pharmaceutical production must comply with:

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- European Medicines Agency (EMA)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

Industrial fermentation particularly in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturing must operate within strict Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations to ensure product safety, efficacy, and quality consistency. Sterilization processes are considered critical control steps and therefore require regulatory oversight, validation, and documentation.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA): In the United States, the FDA enforces Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) regulations under 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211. Compliance is mandatory to demonstrate that sterilization systems (e.g., SIP, filtration, autoclaving) are validated, reproducible, and capable of achieving defined sterility assurance levels. Failure to comply can result in warning letters, product recalls, import alerts, or facility shutdowns.

European Medicines Agency (EMA): The EMA requires adherence to EU GMP guidelines, including Annex 1 for sterile medicinal products. Manufacturers must validate sterilization cycles, conduct environmental monitoring, and implement contamination control strategies. Non-compliance may prevent product authorization within the European Union market.

World Health Organization (WHO): The WHO establishes international GMP standards, particularly for countries supplying vaccines and essential medicines globally. Compliance ensures harmonization of sterility validation practices, supports international procurement programs, and safeguards public health by maintaining consistent manufacturing quality across diverse regulatory environments.

Compliance requirements include:

- Validation protocols

- Biological indicators

- Process documentation

- Environmental monitoring

- Risk assessment (ICH Q9 framework)

Sterility validation must demonstrate reproducibility and statistical confidence.

Contamination Sources in Industrial Fermentation

Understanding contamination vectors is fundamental to designing effective sterilization and contamination control strategies. Industrial fermentation systems are highly nutrient-rich, warm, and aerated conditions that favor rapid microbial growth. Even minimal contamination can outcompete the production organism, alter metabolic profiles, reduce yields, or compromise product safety. Identifying and controlling contamination sources is therefore a core element of bioprocess engineering and GMP compliance.

Raw Materials

Raw materials represent one of the most significant contamination risks because they enter the process in large volumes and may carry substantial bioburden.

Water (must be purified and often sterilized)

Water is the primary component of fermentation media and cleaning systems. Depending on its grade (purified water, WFI), it may contain microorganisms, endotoxins, or dissolved minerals if not properly treated. Systems typically incorporate reverse osmosis, deionization, ultrafiltration, and heat or chemical sanitization. In pharmaceutical fermentation, water is frequently sterilized prior to use to prevent microbial introduction.

Carbon sources (molasses, glucose)

Carbon substrates such as molasses, sucrose, or glucose syrups are derived from agricultural sources and often contain high microbial loads, including spores. These materials can harbor environmental bacteria and fungi. Thermal sterilization or continuous heat treatment is required before introduction into the fermenter to prevent contamination.

Nitrogen sources (corn steep liquor)

Corn steep liquor and other complex nitrogen supplements are rich in amino acids and growth factors but are also susceptible to microbial contamination. Because they are nutrient-dense, even small contamination levels can proliferate rapidly. Proper heat sterilization or filtration is essential before incorporation into sterile media.

Personnel

Human operators are significant contamination vectors due to constant microbial shedding.

Improper aseptic technique

Inadequate training in aseptic manipulations such as poor sampling practices or improper transfer procedures can introduce contaminants. Strict adherence to sterile handling protocols is essential in fermentation environments.

Gowning failures

Incorrect gowning or breaches in protective clothing can release skin flora and airborne particulates into controlled areas. GMP facilities require validated gowning procedures and environmental monitoring to mitigate this risk.

Equipment Leaks

Mechanical failures can compromise system integrity.

Mechanical seals

Agitator shaft seals are potential entry points for contaminants, especially if pressure differentials are not maintained. Seal integrity must be routinely inspected and maintained.

Gaskets

Worn or improperly fitted gaskets may create microgaps that allow microbial ingress. Regular replacement schedules reduce failure risk.

Valve interfaces

Valve seats and diaphragm valves may develop leaks or dead legs, creating contamination niches. Hygienic design minimizes such vulnerabilities.

Phage Contamination

Bacteriophage contamination is particularly problematic in fermentations involving lactic acid bacteria. Phages are highly specific viruses that infect bacterial hosts and can rapidly lyse production cultures, leading to complete batch failure. Unlike bacterial contamination, phages may pass through some filtration systems and resist standard sterilization if not properly validated. Control strategies include strict sanitation, air filtration, culture rotation, and phage-resistant strain development.

Sterilization techniques in industrial microbiology form the structural backbone of fermentation process integrity. The selection of sterilization modality thermal, filtration, chemical, radiation depends on:

- Nature of material

- Heat sensitivity

- Scale of operation

- Regulatory requirements

- Risk profile

Understanding contamination vectors is critical for designing effective sterilization and control strategies in industrial fermentation. Fermentation systems are warm, aerated, and nutrient-rich, creating ideal conditions for rapid microbial growth. Even minor contamination can outcompete production strains, alter metabolic profiles, reduce yields, and compromise product safety. Major contamination sources include raw materials, personnel, equipment, and bacteriophages. Raw materials such as water, carbon, and nitrogen sources can carry microorganisms and spores. Personnel may introduce contaminants through poor aseptic technique or gowning failures. Equipment leaks at seals, gaskets, or valves create entry points. Phages can specifically target production strains, particularly lactic acid bacteria, causing rapid culture collapse. Identifying, monitoring, and controlling these vectors is essential for maintaining sterility, ensuring consistent product quality, and complying with GMP requirements. The convergence of engineering design, microbiological principles, and regulatory science ensures that fermentation systems operate as closed, controlled ecosystems. In modern bioprocessing, sterilization is not a discrete step but an integrated, validated, and continuously monitored framework safeguarding productivity, product quality, and patient safety. In an era of increasing biopharmaceutical complexity and global regulatory scrutiny, robust sterilization strategies remain indispensable to industrial microbiology.

References

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.