Beer production is an ancient and intricate biochemical process that has evolved over thousands of years. It combines elements of agriculture, microbiology, chemistry, and engineering to transform cereal grains, most commonly barley, into one of the world’s most popular alcoholic beverages. Each stage of the brewing process—from malting to packaging—plays a critical role in determining the final product’s flavor, aroma, clarity, alcohol content, and shelf life. This comprehensive overview details the sequential stages of beer production, highlighting the scientific principles and technological techniques underpinning modern brewing practices.

1. Malting: Unlocking the Enzymatic Potential of Barley

Malting is the foundational step in the brewing process. It involves the controlled germination of cereal grains, typically barley, under specific environmental conditions. The primary purpose of malting is to activate and develop key hydrolytic enzymes—most notably amylases and proteases—which are essential for breaking down the grain’s complex macromolecules into fermentable substrates during subsequent stages of beer production.

Barley grains are chosen for their high starch content and ability to produce the necessary enzymes upon germination. During malting, the grains undergo significant biochemical changes, including the mobilization of stored nutrients and partial hydrolysis of starches and proteins. These transformations convert the hard, nutrient-dense grain into a more bioavailable form suitable for yeast metabolism in later stages.

While endogenous yeasts are naturally present on barley grains, they are not typically responsible for beer fermentation. However, malting plays a role in removing potential contaminants, including undesirable wild yeasts, and creates a clean substrate for the inoculated brewing yeast strains. The malting process consists of three sub-stages: steeping, germination, and kilning.

1.1 Steeping: Initiating Germination

Steeping marks the beginning of malting and involves soaking cleaned barley grains in water for a period typically lasting 48 hours. The grains are submerged in large steeping vessels or tanks, where the water is periodically drained and replaced every 6–8 hours to ensure freshness and prevent microbial spoilage.

The purpose of steeping is to increase the moisture content of the barley from around 12% to approximately 42–46%, which is the threshold required to initiate germination. This hydration activates metabolic pathways in the barley embryo and initiates the synthesis of key enzymes. After steeping, the hydrated grains—now referred to as “steeped barley”—are transferred to the germination floor or germination boxes for the next phase.

Aeration during steeping is critical. Adequate oxygen levels prevent anaerobic conditions that could damage the embryo or promote undesirable microbial activity. The temperature is typically maintained around 18–20°C to ensure optimal enzymatic activation.

1.2 Germination: Enzyme Synthesis and Endosperm Modification

Germination is the phase during which the barley kernels begin to sprout under carefully controlled temperature and humidity conditions. This stage typically lasts 3–5 days and occurs on germination floors or in automated germination vessels. During germination, the embryo continues to develop, and enzymes such as α-amylase, β-amylase, proteases, and β-glucanases are synthesized or activated.

These enzymes begin breaking down the endosperm’s complex carbohydrates and proteins into simpler molecules, rendering the grain’s internal structure friable. This “modification” is critical for ensuring that the starch and protein components of the malt can be easily accessed during mashing. Germination is halted at the point where the rootlets (“chits”) appear but before full seedling growth occurs.

1.3 Kilning: Halting Germination and Enhancing Flavor

Once germination has achieved sufficient enzymatic development, the process is arrested by kilning—a carefully controlled drying operation. The main goals of kilning are to reduce the moisture content to below 5%, preserve the enzymatic integrity of the malt, and develop flavor and color compounds through Maillard reactions and caramelization.

Kilning typically proceeds in three phases: initial free drying (30–50°C), intermediate drying (up to 70°C), and final curing (which can range from 80°C to over 100°C depending on the beer style). For lighter beers such as pilsners, the final temperature is kept low to preserve enzyme activity. For darker beers, higher temperatures are employed to develop rich color and toasty, caramel-like flavors.

The kilned malt, known as malted barley, is cooled and subjected to rootlet removal before storage. This finished malt is now enzymatically active, friable, and ready for milling and mashing.

2. Milling: Preparing Malt for Hydrolysis

Milling is the mechanical process of crushing malted barley into grist—a coarse powder that facilitates efficient enzymatic action during mashing. The primary goal is to break open the grain kernels while preserving the integrity of the husks, which serve as a natural filtration medium in the later lautering step.

There are several types of mills used in the brewing industry, including roller mills and hammer mills. The desired degree of fineness depends on the brewing method. A finer grind increases extract yield but may hinder wort filtration, while a coarser grind ensures better drainage but might compromise sugar extraction.

Optimal milling ensures that the endosperm is fully exposed to enzymatic hydrolysis during mashing while the husk structure remains intact to form a good filtration bed during lautering.

3. Mashing: Converting Malt Starch to Fermentable Sugars

Mashing is the key enzymatic stage of beer production. In this process, the milled malt is mixed with hot water in a mash tun under carefully controlled temperatures and pH levels. The objective is to activate malt enzymes to convert starches into fermentable sugars (mainly maltose) and to degrade proteins into amino acids and peptides.

3.1 Process Details

The mash is typically held at a sequence of temperatures to favor different enzymatic activities:

- β-glucanase rest (35–45°C): Breaks down cell wall components.

- Protease rest (45–55°C): Degrades proteins into free amino nitrogen (FAN) for yeast nutrition.

- Amylase rest (62–72°C): Converts starch into fermentable sugars.

The resulting liquid, known as wort, contains a complex mixture of sugars, amino acids, peptides, vitamins, and minerals—all essential nutrients for yeast growth during fermentation.

There are two common mashing techniques:

- Infusion mashing: The mash is heated progressively without boiling.

- Decoction mashing: A portion of the mash is removed, boiled, and returned to the mash tun to raise the temperature.

After mashing, the mash is transferred to a lauter tun, where the solid husks form a filter bed. The sweet wort is separated from the grain residues and then sparged (rinsed) with hot water to extract remaining sugars.

4. Wort Boiling and Cooling: Sterilization and Flavor Development

Once the sweet wort is extracted from the mash tun, it undergoes a crucial transformation in the boiling and cooling stage. The wort is transferred to a specialized vessel known as a boiling kettle or wort copper, where it is subjected to vigorous boiling, typically for 60 to 90 minutes. This stage serves several essential purposes in beer production, contributing to both the stability and final sensory profile of the beer.

Key Functions of Wort Boiling:

- Enzyme Inactivation: Boiling halts all enzymatic activity remaining from the mashing stage. This is necessary to stabilize the composition of the wort and ensure that further enzymatic breakdown of starches and proteins does not occur, which could negatively affect fermentation and flavor.

- Sterilization: The high temperature of boiling ensures microbial sterilization, effectively eliminating any unwanted or spoilage microorganisms that might have survived earlier stages. This is critical for preventing contamination during fermentation and extending the shelf life of the final product.

- Protein Coagulation and Hot Break Formation: Boiling causes the denaturation and coagulation of proteins, polyphenols, and other suspended solids. These substances clump together to form what is known as the “hot break.” The hot break precipitates out of the wort, aiding in clarification and reducing haze-forming compounds that could affect the beer’s clarity and stability.

- Isomerization of Hop Acids: One of the most critical chemical reactions during boiling involves the hops. Hops are added at various stages of the boil, and the heat causes alpha acids in the hops to isomerize into iso-alpha acids, which are soluble in wort and impart the characteristic bitterness of beer. Early hop additions provide more bitterness, while later additions contribute to aroma and flavor.

- Volatilization of Unwanted Compounds: Boiling also helps to remove undesirable volatile compounds such as dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which can impart off-flavors reminiscent of cooked vegetables.

After boiling, the wort contains suspended solids and hop residues known as trub. To clarify the wort, it is often transferred to a whirlpool vessel, where centrifugal force allows the trub to settle in the center of the vessel, leaving behind a clearer wort.

The clarified wort is then rapidly cooled using a plate or shell-and-tube heat exchanger to fermentation temperature—typically between 10–20°C, depending on whether an ale or lager yeast will be used. Rapid cooling is essential to avoid microbial contamination, minimize oxidation, and prepare the wort for optimal yeast performance during fermentation.

5. Fermentation: Bioconversion of Sugars to Alcohol and CO₂

Fermentation is the most biologically dynamic and metabolically significant stage in beer production. This critical process marks the transformation of sweet wort—a sugar-rich liquid extracted during mashing—into alcoholic beer. The process is catalyzed by brewer’s yeast, which converts fermentable sugars such as maltose, glucose, fructose, and sucrose into ethanol (alcohol), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and a range of secondary metabolites that contribute to the beer’s flavor, aroma, and mouthfeel.

At this stage, the wort, which has been sterilized through boiling and subsequently cooled, is transferred into fermentation vessels. It is here that selected yeast strains are introduced in a process known as pitching. The environment must be carefully controlled in terms of temperature, oxygen level, and pH to ensure optimal yeast performance and minimize contamination. While oxygen is initially important for yeast cell membrane synthesis, fermentation itself is anaerobic.

There are two main types of yeast employed in beer fermentation:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae (top-fermenting yeast): Commonly used for producing ales, porters, and stouts. This yeast ferments at warmer temperatures, typically ranging between 18°C and 22°C. It is known as a top-fermenting yeast because the yeast cells tend to rise to the surface of the fermenting wort, forming a thick foam or krausen. S. cerevisiae completes fermentation relatively quickly—often within 3 to 7 days—making it suitable for faster beer production cycles and for beers with more complex estery and fruity aromas.

- Saccharomyces pastorianus (formerly known as S. carlsbergensis, a bottom-fermenting yeast): This yeast strain is used in the production of lagers, pilsners, and other bottom-fermented beers. It operates at lower fermentation temperatures (typically between 7°C and 15°C) and settles at the bottom of the fermentation vessel. This yeast tends to produce fewer esters and phenols, resulting in cleaner and crisper beer flavors. Lagers also typically require a longer fermentation and maturation time, often several weeks.

During fermentation, ethanol and CO₂ are the primary byproducts. The CO₂ can be captured and later used for beer carbonation. In addition to alcohol and gas, yeast produces various byproducts such as esters, aldehydes, higher alcohols, and organic acids, all of which subtly influence the beer’s sensory profile. Once the desired alcohol level is reached and fermentation ceases, the beer undergoes conditioning or aging to allow flavor refinement and yeast sedimentation.

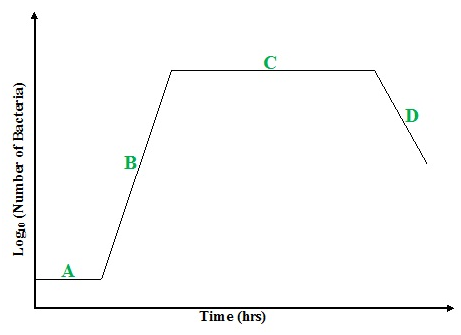

5.1 Fermentation Dynamics

Primary fermentation is one of the most critical stages in beer production and typically lasts between 4 to 10 days. The duration depends on several factors, including the specific style of beer being brewed, the fermentation temperature, the yeast strain employed, and the sugar concentration in the wort. During this phase, the yeast—most commonly Saccharomyces cerevisiae for ales or Saccharomyces pastorianus (formerly S. carlsbergensis) for lagers—actively metabolizes the fermentable sugars present in the wort. These sugars include maltose, maltotriose, glucose, and small amounts of fructose and sucrose. The primary metabolic products of fermentation are ethanol and carbon dioxide (CO₂), but yeast also produces a wide array of secondary metabolites such as esters, higher alcohols, diacetyl, acetaldehyde, and sulfur compounds. These by-products significantly influence the aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel of the final beer.

Temperature control during fermentation is vital, as yeast metabolism generates heat, which can quickly raise the temperature of the fermenting beer. Excessive heat can cause yeast stress, off-flavors, and even fermentation stalling. Therefore, modern fermenters are equipped with efficient cooling systems, including jackets and coils, to maintain optimal temperatures—typically around 18–22°C for ales and 8–14°C for lagers. Temperature precision ensures the development of desired flavor profiles and maintains yeast viability and vitality throughout the fermentation period.

The beer at the end of primary fermentation is commonly referred to as “green beer.” Although it contains alcohol and carbonation, green beer has an immature character, often marked by sharp flavors, unbalanced aromas, and the presence of undesired intermediates like diacetyl and acetaldehyde. These compounds require further conversion or removal through additional conditioning. As a result, green beer undergoes a secondary fermentation or conditioning process—often called maturation or lagering—at lower temperatures. This step allows for the natural clarification, flavor refinement, and stabilization of the beer before it proceeds to carbonation, packaging, and final consumption. Understanding the complex biochemical and physical transformations during primary fermentation is essential for controlling the quality, consistency, and style-specific characteristics of beer.

6. Conditioning (Secondary Fermentation and Maturation)

Conditioning, often referred to as lagering (especially in lager-style beers), is the post-primary fermentation stage of beer production where the green, immature beer undergoes crucial biochemical transformations that refine its overall quality. This stage plays a vital role in improving the beer’s flavor, clarity, aroma, carbonation, and overall drinkability. Conditioning is typically conducted at low temperatures and may last anywhere from a few weeks to several months, depending on the beer style and desired final characteristics.

6.1 Secondary Fermentation

One of the central processes during conditioning is secondary fermentation, which occurs when a small amount of fermentable sugar (often known as priming sugar) is added to the beer after the initial fermentation has completed. This sugar addition reactivates the remaining yeast cells, prompting them to ferment the new sugar slowly at cooler temperatures—typically between 0–4°C. This low-temperature fermentation process offers several key advantages:

- Clarification: Yeast cells and other particulate matter (such as proteins and polyphenols) flocculate and settle out of suspension more efficiently at lower temperatures. This process results in a clearer, brighter beer, free from haziness or turbidity.

- Carbonation: The carbon dioxide (CO₂) generated during secondary fermentation naturally carbonates the beer. This internal carbonation improves mouthfeel, enhances the beer’s body, and contributes to better head retention when poured.

- Flavor Maturation: During this stage, green flavors—often described as harsh, sulfurous, or overly yeasty—are mellowed. Various volatile compounds are either removed or transformed into more pleasant-tasting substances through continued yeast metabolism and other chemical reactions.

- Stabilization: Extended conditioning improves the physical and microbiological stability of the beer, making it less prone to spoilage or flavor degradation.

Additionally, this stage is an opportunity to introduce fining agents that aid in further clarification and stabilization. Common fining agents include:

- Isinglass (a collagen-derived substance from fish bladders)

- Gelatin (animal-based protein)

- Silica gel or PVPP (used to remove polyphenols and proteins)

These agents bind with haze-forming particles and assist in their removal either by sedimentation or filtration.

Some specialty beers may also receive added flavoring components such as fruit extracts, spices, or wood infusions during conditioning, contributing to more complex flavor profiles.

7. Filtration and Pasteurization: Ensuring Stability and Shelf-Life

Once conditioning is complete and the beer has reached its intended flavor and clarity, it is typically subjected to filtration and/or pasteurization. These processes are essential for ensuring microbiological safety, long-term stability, and consistent quality, especially for commercial beers distributed at scale.

7.1 Filtration

Filtration removes residual yeast cells, proteins, polyphenols, and other haze-causing or spoilage-prone materials from the beer. There are several types of filtration systems used in the brewing industry:

- Sheet Filters: These use cellulose-based filter sheets with varying pore sizes to physically trap particulates.

- Diatomaceous Earth (DE) Filters: DE filters use fossilized diatoms as a porous medium to capture fine particles, making them especially effective for large-volume brewing operations.

- Membrane Filters: These filters consist of synthetic polymer membranes with precise pore sizes, often used as the final filtration step to achieve microbiological sterility.

Filtered beer is visually clearer, more stable over time, and less susceptible to flavor changes due to yeast autolysis or microbial spoilage.

7.2 Pasteurization and Cold Sterilization

To further ensure the beer’s shelf stability, brewers may employ pasteurization or cold sterilization:

- Pasteurization involves heating the beer to temperatures of around 60–70°C for 15–30 minutes. This mild heat treatment effectively kills spoilage organisms like wild yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, and acetic acid bacteria without significantly affecting the beer’s flavor if performed correctly.

- Cold Sterilization (Cold Filtration) involves passing the beer through ultra-fine sterile membranes (often 0.45 μm or smaller), which physically remove microorganisms without the need for heat. This technique is often used in conjunction with cold storage and is particularly favored by brewers aiming to preserve delicate aroma compounds that might be altered by heat.

While these methods extend the beer’s shelf life, some craft breweries deliberately avoid pasteurization and/or filtration to retain fuller body, richer aromas, and more nuanced flavors. However, unfiltered and unpasteurized beers must be kept refrigerated and consumed within a shorter time frame to prevent spoilage.

Ultimately, the decision to filter and/or pasteurize depends on factors such as beer style, production volume, intended market, and desired shelf stability.

8. Packaging: Delivering Beer to Consumers

Packaging marks the final stage of the brewing process. The clarified, carbonated beer is transferred into kegs, bottles, or cans using highly automated systems that minimize oxygen ingress—crucial for preserving flavor and shelf life.

Prior to packaging, CO₂ may be forcefully injected to adjust carbonation levels. Antioxidants like ascorbic acid or sulfites may be added to prevent oxidation. Bottles and cans are sealed, labeled, and often coded with batch information for traceability.

Conclusion

The production of beer is a meticulously orchestrated process involving a series of biochemical, physical, and mechanical steps that transform barley into a flavorful, carbonated alcoholic beverage. From the activation of enzymes during malting to the final packaging for distribution, each stage must be carefully controlled to ensure product quality, consistency, and safety. Mastery of these processes enables brewers to create a diverse array of beer styles, each with its unique profile of aroma, taste, appearance, and alcohol content. The science of brewing continues to evolve with advancements in microbiology, automation, and sustainability, further enhancing both the art and efficiency of beer production.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.