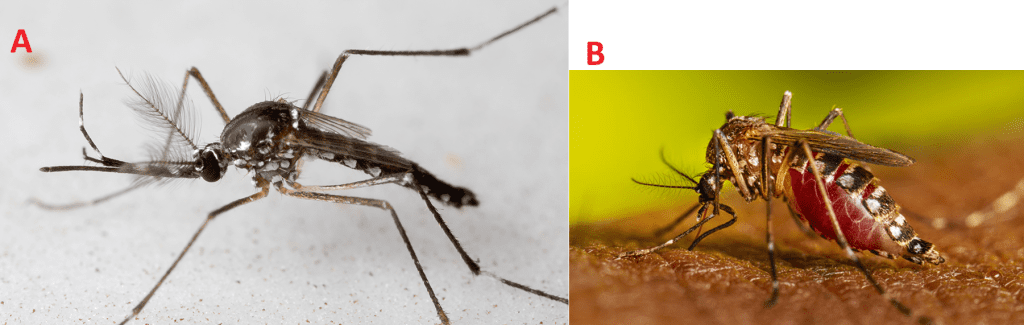

Chikungunya (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne viral disease marked by sudden onset fever and severe joint pain. First clinically identified during an outbreak in Tanzania in 1952-1953, its name derives from the Makonde phrase meaning “that which bends up,” reflecting the stooped posture of sufferers afflicted by debilitating arthralgia (pain in one or more joints in the body). Though historically limited to Africa and Asia, the past two decades have seen its spread into Europe and the Americas. The virus’s rapid expansion, coupled with its significant morbidity, underscores the urgency of understanding its biology, transmission, clinical impact, and control. CHIKV is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, mainly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. These mosquitoes are daytime feeders, breeding in stagnant water found in urban and suburban environments. Aedes aegypti thrives in tropical regions, while Aedes albopictus, known as the Asian tiger mosquito, has adapted to cooler climates and expanded its range globally. When an infected mosquito bites a human, it transmits CHIKV, causing symptoms like fever, joint pain, and rash. Controlling mosquito populations through eliminating breeding sites and using protective measures is key to preventing Chikungunya outbreaks.

Biology Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV)

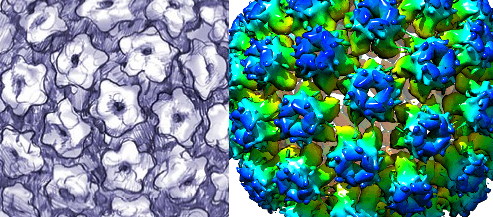

Chikungunya virus belongs to the family Togaviridae, genus Alphavirus. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus, measuring ~11.8 kb in size, encoding four non-structural proteins (nsP1–4) essential for replication, and five structural proteins including envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 critical for cell attachment, fusion, and immune recognition. E1 mediates membrane fusion under acidic conditions while E2 binds cellular receptors. Genetic lineages of the Chikungunya (CHIKV) include West African, East/Central/South African (ECSA), Asian, and Indian Ocean lineage (IOL), each with temporal and geographic patterns.

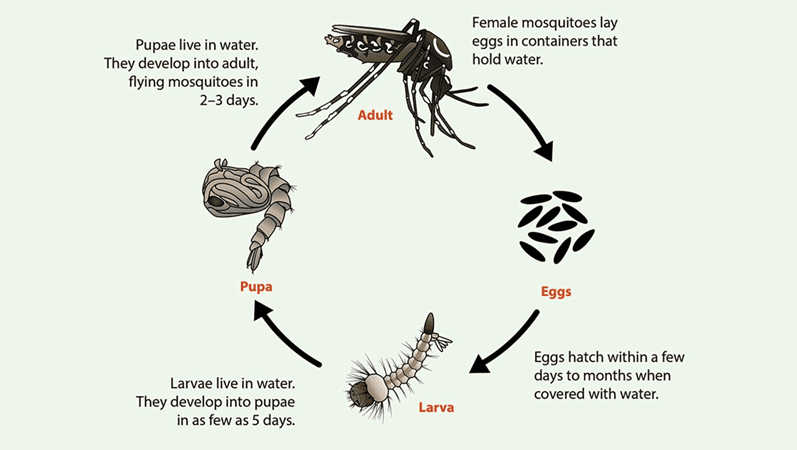

Life Stages of Aedes Species Mosquitoes

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes live in many areas of the globe, and their life cycle – from egg to adult usually takes about 7-10 days. Adult females lay their eggs (Figure 1) on the inner walls of containers just above the waterline, where they stick firmly and can survive drying out for up to eight months, even though winter. Only a small amount of water is needed for egg-laying, making items such as bowls, cups, fountains, tires, barrels, and vases ideal breeding sites. When water from rain or sprinklers covers the eggs, larvae (Figure 1) hatch and live in the water, moving actively and earning the nickname “wigglers.” Larvae develop into pupae (Figure 1), which also live in the water but do not feed, and from which adult mosquitoes emerge and fly away. The male Aedes mosquitoes does not bite or feed on human blood (Figure 2). Only female Aedes mosquitoes bite, requiring blood to produce eggs. After feeding, they search for water sources to lay the next generation of eggs. Aedes aegypti prefer living near and biting humans, often indoors or outdoors, while Aedes albopictus feed on both people and animals and are commonly found outdoors near homes or in wooded areas. Both species have limited flight ranges, typically traveling only a few blocks during their lifetime.

Life Cycle of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV)

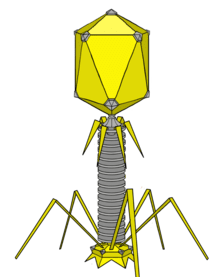

The life cycle of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) involves two distinct but interconnected hosts – the mosquito vector (primarily Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) (Figure 3) and the vertebrate host (humans and other primates). The virus must complete its replication process in both hosts to sustain transmission in nature. Within either cell type, CHIKV follows the general replication strategy of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses, with some unique features that influence its pathogenesis and epidemiology, and these are described as follows:

1. Attachment & Entry

This is the stage at which the CHIKV attaches and penetrates the host cell after a blood meal. In the vertebrate host, infection begins when an infected female mosquito injects saliva containing CHIKV into the skin during a blood meal. The virus targets susceptible cells such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages. The viral envelope glycoprotein E2 binds to specific cell surface receptors, the most well-characterized being Mxra8 (Matrix Remodeling Associated protein 8) in humans. This binding facilitates internalization via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, a process in which the plasma membrane invaginates to form a vesicle enclosing the invading virus.

2. Fusion & Uncoating

At this stage, the CHIKV uncoats in order to release its nucleic acid molecule – which is an RNA genome. Once inside the endosome, the acidic environment triggers conformational changes in the E1 and E2 proteins. The E2 protein retracts, exposing E1, which mediates fusion between the viral envelope and the endosomal membrane. This fusion event releases the viral RNA genome into the host cell cytoplasm, where replication takes place entirely in the cytosol.

3. Translation of Non-Structural Proteins

Being a positive-sense RNA virus, the CHIKV genome acts directly as messenger RNA (mRNA). Host ribosomes immediately translate the 5′-proximal portions of the genome into a polyprotein that is subsequently cleaved into four non-structural proteins (nsP1–nsP4). These proteins assemble into membrane-associated replicase complexes, which remodel host cell membranes (often forming spherules) to create a protected microenvironment for RNA synthesis.

4. Replication

The replicase complex first synthesizes a complementary negative-sense RNA strand, which serves as a template for producing new positive-sense genomic RNAs and shorter sub-genomic RNAs. The latter is crucial for the expression of structural proteins. This replication phase dramatically increases the intracellular viral RNA load, setting the stage for massive viral protein production.

5. Translation of Structural Proteins

The sub-genomic RNA is translated into another polyprotein containing the capsid protein, E3, E2, 6K, and E1. The capsid protein self-cleaves from the polyprotein and begins encapsidating newly synthesized genomic RNA. The remaining glycoproteins E1 and E2 are processed and glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus, then trafficked to the plasma membrane.

6. Assembly & Release

This is the stage where the newly synthesized viral components (i.e., the capsid protein and genomic RNA) are gathered to form a new mature CHIKV that go on to infect new host cells. At the plasma membrane, the nucleocapsid (capsid protein + genomic RNA) interacts with the cytoplasmic tails of E2 embedded in the membrane. This interaction drives budding, during which the nucleocapsid acquires its lipid envelope studded with E1/E2 glycoprotein spikes. Mature virions are released into the extracellular space, ready to infect new cells.

Replication of CHIKV in the Mosquito Vector

In mosquitoes, CHIKV enters through an infected blood meal and initially infects midgut epithelial cells. After replication, it crosses the midgut barrier, disseminating via the hemolymph to secondary tissues, most importantly the salivary glands. Once the virus reaches and replicates in salivary gland cells, it can be transmitted to another host during feeding. This period between ingestion and the ability to transmit is known as the extrinsic incubation period, typically lasting 2-10 days depending on temperature and vector species.

This dual-host cycle enables CHIKV to persist in nature, adapt to different environments, and occasionally expand its geographical range when vectors are introduced into new areas.

Types (Genotypes & Strains) of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV)

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is genetically diverse, and phylogenetic analyses have identified four major genotypes that reflect both geographical distribution and evolutionary history. While all share similar structural and functional characteristics, subtle genetic differences influence transmission dynamics, vector specificity, and outbreak potential.

- West African Lineage

This genotype is largely confined to West Africa, where it circulates primarily in a sylvatic cycle between forest-dwelling Aedes mosquitoes and non-human primates, occasionally spilling over to humans. Outbreaks in this region have historically been sporadic and localized, with limited evidence of large-scale epidemics.

- East/Central/South African (ECSA) Lineage

The ECSA lineage has a wide distribution across eastern, central, and southern Africa, and it has also been detected in the Indian Ocean region. This genotype has been responsible for both rural sylvatic transmission cycles and urban outbreaks. It forms the genetic backbone for the Indian Ocean lineage and has demonstrated the ability to adapt to new vectors and ecological conditions.

- Indian Ocean Lineage (IOL)

Emerging as a derivative of the ECSA genotype, the IOL was first recognized during the massive 2005-2006 outbreaks on Réunion Island, Mauritius, and parts of India. A defining genetic feature of this lineage is the E1-A226V mutation, which significantly enhances replication and transmission efficiency in Aedes albopictus, a mosquito species more tolerant of cooler climates and present in temperate regions like in the United States. This adaptation enabled explosive spread in areas previously considered low risk for CHIKV transmission.

- Asian Lineage

Historically circulating in Southeast Asia, the Asian lineage has also been implicated in more recent outbreaks in the Pacific islands and the Americas, beginning in 2013. In the Americas, it coexists with Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, both competent vectors. Although the Asian lineage lacks the E1-A226V mutation, its introduction into densely populated tropical and subtropical regions has led to sustained community transmission and substantial morbidity.

Pathogenesis of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

Following a mosquito bite, CHIKV infects fibroblasts and endothelial cells locally, then disseminates via bloodstream to target tissues – primarily joints, muscles, tendons, skin, liver, and the central nervous system in rare cases. Host immune response includes early production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), which may contribute to both viral clearance and joint inflammation. Severe joint pain arises from infection of synovial fibroblasts and macrophages, resulting in synovitis. In most patients, acute symptoms resolve; however, persistent joint pain (chronic chikungunya) occurs in a subset – due to viral persistence or prolonged immune activation. Severe disease is uncommon but may include neurological complications (encephalitis), myocarditis, or prolonged alteration of hepatic and renal function.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

Accurate laboratory diagnosis of chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection is essential for confirming outbreaks, differentiating it from other febrile illnesses such as dengue or Zika, and guiding public health responses. Diagnostic methods focus on detecting either the virus itself, viral components, or the host’s immune response, with the choice of test largely depending on the stage of illness. The following are some laboratory diagnosis explored for CHIKV infection:

1. Direct Detection

In the acute phase of CHIKV infection, usually within the first 5-7 days after symptom onset – CHIKV is present in high titers in the blood. During this period, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the gold standard for detecting viral RNA in serum or plasma, offering high sensitivity and specificity. Virus isolation in susceptible cell lines such as Vero cells or C6/36 mosquito cells can also be performed, but this method is slower, requires specialized biosafety facilities, and is primarily used for research or detailed virological studies rather than routine diagnostics in hospitals.

2. Antigen Detection

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) using lateral flow immunoassay technology can detect CHIKV antigens in blood samples, typically targeting the E1 envelope protein. These assays can yield results within 15-30 minutes and are useful in field settings. However, the performance of these RDTs varies, with sensitivity often lower than molecular techniques, particularly when viral loads are low.

3. Serology

From about day 5 of illness onwards, the host immune system produces IgM antibodies, detectable by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or immunofluorescence assay (IFA). IgM typically persists for several weeks to months, while IgG antibodies develop later and can last for years, indicating past exposure. Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) remain the reference standard for confirming serological findings and distinguishing CHIKV from related alphaviruses.

Treatment of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

As of 2025, there is no specific antiviral drug or licensed vaccine for chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection. Management focuses on symptomatic relief, prevention of complications, and addressing persistent symptoms in chronic cases.

1. Symptomatic Relief

The acute phase of CHIKV infection is characterized by high fever, severe joint and muscle pain, headache, and rash. Supportive care remains the cornerstone of management. Patients are advised to rest adequately, maintain proper hydration, and use analgesics or antipyretics to reduce fever and pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen are often effective for arthralgia. However, aspirin should be avoided in children because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome, and caution is needed in adults with bleeding risk, particularly when dengue co-infection has not been ruled out.

2. Severe or Chronic Cases

While most patients recover within 1-2 weeks, a subset develops chronic arthralgia or arthritis-like symptoms lasting months to years. In such cases, rheumatological evaluation may be warranted. Management may involve prolonged NSAID use, short courses of corticosteroids during inflammatory flares, or in refractory cases, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine. Physical therapy can help restore mobility and reduce stiffness.

3. Emerging Treatments

Experimental antivirals targeting CHIKV’s non-structural proteins (nsPs) aim to block viral replication. Monoclonal antibodies that neutralize viral particles are also in development, potentially useful for post-exposure prophylaxis or severe disease. Host-directed therapies, which modulate the immune response to reduce inflammation and prevent chronic symptoms, are under investigation.

4. Vaccine Development

Several vaccine platforms including live attenuated viruses, virus-like particles (VLPs), recombinant viral vectors, and mRNA vaccines have shown promising immunogenicity in clinical trials. Some candidates have reached Phase 3 studies, but as of mid-2025, none have received global regulatory approval. Overall, treatment remains supportive, but ongoing research offers hope for targeted therapies and preventive vaccines in the near future.

Epidemiology of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

CHIKV is endemic in parts of Africa and Asia, with episodic outbreaks having increased since the 2000s. In 2005-2006, massive outbreaks occurred in the Indian Ocean islands, India, and Southeast Asia, with millions infected. In the late 2010s and early 2020s, autochthonous transmission was identified in southern Europe (e.g., Italy, France) tied to Aedes albopictus vectors and in the Americas, beginning in the Caribbean in 2013 then spreading rapidly across Latin America.

Urban transmission cycles predominate, with Aedes aegypti and A. albopictus serving as primary vectors. Global air travel, climate change expanding vector habitat, and urbanization fuel emergence in new locales. Co-circulation with dengue and Zika in many tropical regions complicates surveillance and strain identification.

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) has a complex epidemiological profile shaped by its vector ecology, viral genetics, and human behavior. First identified in Tanzania in the early 1950s, the virus remained relatively localized for decades, causing periodic outbreaks in Africa and Asia. However, since the early 2000s, CHIKV has undergone a remarkable geographic expansion, driven by a combination of ecological, environmental, and societal factors.

Endemic Regions and Early Spread of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

CHIKV is historically endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Southeast Asia, where it circulates in two transmission cycles:

- Sylvatic cycle – involving Aedes mosquitoes and non-human primates in forested areas, with occasional spillover to humans.

- Urban cycle – sustained human–mosquito–human transmission, primarily mediated by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus.

In Africa, outbreaks were typically sporadic, localized, and linked to the sylvatic cycle, whereas in Asia, sustained urban transmission has long been documented.

Global Resurgence of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Since the 2000s

The early 21st century marked a turning point in CHIKV epidemiology. Large-scale epidemics emerged across the Indian Ocean islands, India, and Southeast Asia between 2005 and 2006, infecting millions. The Indian Ocean lineage (IOL), carrying the E1-A226V mutation, increased transmission efficiency in Aedes albopictus, enabling spread to regions beyond the tropics.

Expansion of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) into New Regions

From 2013 onward, CHIKV made a significant leap into the Americas. Autochthonous transmission was first reported in the Caribbean, quickly followed by spread throughout Central and South America. The virus established sustained circulation in countries from Brazil to Mexico, causing millions of cases within a few years.

In Europe, local transmission has been documented in countries such as Italy and France, primarily during warmer months when Aedes albopictus populations peak. While outbreaks here remain relatively small, they underscore the potential for CHIKV to establish seasonal transmission in temperate regions.

Factors Driving Spread of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

Several factors have facilitated CHIKV’s rapid expansion:

- Vector adaptability – Aedes albopictus thrives in both tropical and temperate climates, expanding the virus’s ecological niche.

- Global travel and trade – Infected travelers can introduce CHIKV to new areas where competent vectors exist.

- Urbanization – Dense human populations with poor vector control create ideal conditions for sustained transmission.

- Climate change – Rising temperatures and altered rainfall patterns expand Aedes habitats into higher altitudes and latitudes.

Co-Circulation of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) with Other Arboviruses

CHIKV often co-circulates with dengue virus (DENV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) in tropical and subtropical regions. This overlapping distribution complicates clinical diagnosis due to similar symptoms and may lead to misclassification in surveillance data.

Current Situation and Outlook of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV)

As of 2025, CHIKV remains a significant public health challenge in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, with intermittent introductions into Europe and other temperate regions. Seasonal outbreaks are likely to continue in endemic regions, and sporadic transmission in temperate areas may become more frequent if climate conditions continue to favor vector expansion. Ongoing genomic surveillance, integrated vector management, and strengthened health systems will be key to reducing future transmission and mitigating the impact of this increasingly global arbovirus.

Public Health Implications of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

Chikungunya’s main burden is morbidity, not mortality – though it can be incapacitating acutely and chronically. This results in noticeable economic and social impact: loss of productivity, healthcare utilization, long-term disability from chronic arthralgias. Syndromic overlap with dengue and Zika can lead to misdiagnosis and overwhelmed health systems during outbreaks. The absence of specific treatment or widespread vaccine heightens reliance on surveillance, vector control, and public education. The risk of introduction into temperate zones underscores the need for integrated surveillance and response systems, as well as international collaboration.

The public health significance of chikungunya lies less in its mortality rate which is generally low, and more in its high morbidity and capacity to cause widespread, debilitating illness. The acute disease can incapacitate large segments of the population for days to weeks, while a significant proportion of patients develop chronic joint pain or arthritis-like symptoms that may persist for months or years. These prolonged effects contribute to reduced productivity, increased healthcare visits, and in some cases, long-term disability.

Outbreaks can place immense strain on healthcare systems, particularly in low-resource settings. The clinical overlap between chikungunya, dengue, and Zika makes differential diagnosis challenging, often requiring laboratory confirmation. During epidemics, limited diagnostic capacity can lead to underreporting, misclassification, and delayed response measures.

The lack of specific antiviral treatment and an approved vaccine means that public health efforts rely heavily on vector control, surveillance, and community education. Sustaining these measures requires substantial financial investment, trained personnel, and ongoing community engagement.

Globalization, climate change, and the expanding range of Aedes albopictus increase the likelihood of CHIKV introduction into temperate zones. Such incursions have already occurred in parts of Europe and the Americas, highlighting the need for integrated surveillance systems that link entomological, clinical, and laboratory data.

Ultimately, controlling chikungunya requires international collaboration to strengthen outbreak preparedness, enhance research into therapeutics and vaccines, and promote coordinated vector control strategies capable of addressing multiple co-circulating arboviruses simultaneously.

Prevention and Control of Chikungunya Virus (CHIKV) Infection

No licensed human vaccine currently exists, although experimental candidates are progressing through clinical trials. Thus, prevention relies mainly on vector control and personal protection as follows:

- Environmental measures: Eliminating mosquito breeding sites (including standing water in containers, tires, buckets) through community clean-up campaigns. Introduction of larvivorous fish or bacterial larvicides (e.g., Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis) can be effective.

- Chemical control: Use of insecticides for larval and adult mosquitoes, including space spraying during outbreaks.

- Biological control: Release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, sterile insect technique, or genetically modified mosquitoes to reduce vector populations or transmission capacity.

- Personal protection: Use of insect repellents (DEET, picaridin), protective clothing, window/door screens, bed nets (though Aedes bite during day).

- Public education: Community outreach to raise awareness of source reduction, early symptom recognition, and seeking prompt medical care.

- Surveillance: Sentinel monitoring, early detection systems, and cross-border data sharing aid timely response.

- Outbreak response: Rapid case detection, public warnings, targeted vector control campaigns, and clinical management guidelines.

Bibliography

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.