The success of any industrial fermentation process heavily depends on the efficiency, reliability, and appropriateness of the fermenter used. Among all considerations in the design and construction of fermenters, cost remains a central and decisive factor. In industrial microbiology, profitability is inseparable from technological feasibility. A poorly designed or inappropriately constructed fermenter does not merely risk operational inefficiency; it may lead to inflated production costs, underperformance in microbial yield, resource wastage, and the eventual failure of the entire bioprocess. Therefore, designing a fermenter requires careful integration of scientific, engineering, and economic principles to ensure that the unit meets the demands of the microbial process while remaining economically viable.

The fermenter—also referred to as a bioreactor—is a vessel that provides a controlled environment for the growth and metabolic activity of microorganisms or cells. Whether used for the production of antibiotics, enzymes, biofuels, organic acids, or single-cell proteins, the fermenter must be customized to suit the specific process it is intended for. In doing so, the design must ensure that the biological system is maintained under optimal conditions for maximum product yield, stability, and safety.

The design and construction of fermenters necessitate input from multiple disciplines. Experts in microbiology, biochemistry, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, process control, and industrial economics all contribute uniquely to the development of a robust and efficient fermenter. The collaboration of these diverse fields ensures that all biological, chemical, mechanical, and economic parameters are considered and harmonized.

Multidisciplinary Contributions to Fermenter Design

1. Microbiological Input

Microbiologists play a foundational role in the design and optimization of fermenters. Their expertise provides critical insights into the physiological and metabolic characteristics of the target microorganism, which directly influence the engineering parameters of the bioreactor. These insights include the organism’s nutritional needs, such as preferred carbon and nitrogen sources, trace elements, and vitamins. They also determine environmental conditions essential for optimal growth and productivity—such as temperature range, pH tolerance, oxygen requirements, and resistance or sensitivity to mechanical stress, shear forces, and inhibitory compounds.

For example, obligate aerobes necessitate fermenters equipped with advanced aeration systems—such as spargers, diffusers, and baffles—alongside efficient agitation mechanisms to maintain dissolved oxygen levels. In contrast, strict anaerobes require sealed systems with inert gas flushing (e.g., nitrogen or carbon dioxide) to eliminate oxygen and maintain anaerobic conditions. Furthermore, some microbial strains are prone to foaming or exhibit sensitivity to oxidative stress, which necessitates the inclusion of anti-foaming agents or controlled oxygen delivery mechanisms. These microbiological factors directly inform decisions about vessel geometry, agitation rates, material selection (e.g., corrosion resistance), and the incorporation of sensors for real-time monitoring.

2. Biochemical Considerations

Biochemists contribute to fermenter design by elucidating the intracellular biochemical processes and the metabolic pathways of the production organism. Understanding these processes helps in optimizing nutrient supply, controlling growth rates, and enhancing the yield and quality of the desired bioproduct. By mapping metabolic fluxes and regulatory networks, biochemists can recommend specific substrate feeding strategies—such as batch, fed-batch, or continuous modes—to ensure steady-state conditions or induce desired pathways (e.g., secondary metabolite production).

They also assess the influence of environmental parameters on enzymatic activity and stability. For instance, if a particular product is only synthesized under nutrient-limited or stress-induced conditions, the fermenter must be designed to simulate and maintain such states. Furthermore, by identifying toxic by-products or feedback inhibitors generated during fermentation, biochemists guide the integration of detoxification systems, selective membranes, or intermittent product removal mechanisms.

Biochemists also contribute to the development of kinetic models that describe microbial behavior—covering growth dynamics, substrate uptake, product formation, and biomass accumulation. These models are crucial for scaling up processes from laboratory to pilot and industrial scales. They enable predictive control strategies that minimize variability and enhance reproducibility.

The collaboration between microbiologists and biochemists ensures that the fermenter is not only tailored to the biological characteristics of the microorganism but also optimized for maximum efficiency and product yield. Their combined knowledge informs everything from basic vessel design to complex process control and monitoring systems, making their multidisciplinary contributions indispensable to modern bioprocess engineering.

3. Chemical Engineering Involvement

Chemical engineers play a pivotal role in optimizing the physical and chemical environment of the fermentation process, ensuring that microbial or cell cultures can grow efficiently and produce the desired metabolites. Their expertise is essential for maintaining optimal reaction conditions through the careful control of variables such as temperature, pH, pressure, agitation, and gas exchange.

One of the key tasks of chemical engineers is managing mass transfer processes, particularly the supply of oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide in aerobic fermentations. They design systems that enhance the solubility and distribution of gases throughout the fermentation broth. This includes optimizing the sparging system and agitator design to improve oxygen transfer rates (OTR) and carbon dioxide stripping. They also regulate the concentration of nutrients and metabolites to prevent inhibition or nutrient limitation that could affect productivity.

In addition, chemical engineers ensure efficient heat transfer within the fermenter, which is crucial because microbial activity generates heat. They develop heat exchange systems, such as internal coils or external jackets, to maintain a stable temperature within narrow operational limits. Foam control is another important aspect, as excessive foaming can disrupt the fermentation process. Engineers integrate sensors and automatic antifoam dosing systems to keep foam at acceptable levels.

Chemical engineers also lead scale-up operations. Transitioning from bench-top to pilot and then to industrial-scale fermenters requires maintaining consistent hydrodynamic and thermodynamic conditions. Engineers use mathematical models and simulations to predict how changes in scale will affect mixing, gas exchange, and heat removal. They ensure that larger systems maintain the same performance characteristics as smaller ones, minimizing shear stress on cells while preserving productivity and product quality.

4. Mechanical Engineering Contributions

Mechanical engineers contribute significantly to the physical realization of fermentation systems. They take the functional requirements defined by microbiologists, chemical engineers, and process technologists and turn them into mechanical designs that meet the demands of industrial-scale fermentation. This includes the design and fabrication of the fermenter vessel, agitators, seals, baffles, spargers, and heat exchange components.

Vessel design must account for factors such as operating pressure, temperature, corrosion resistance, and mechanical stress. Mechanical engineers select appropriate construction materials—such as stainless steel or glass-lined steel—that can withstand corrosive environments while maintaining structural integrity over repeated sterilization cycles. They also ensure that the geometry of the vessel supports effective mixing and mass transfer, reducing dead zones and ensuring homogeneity.

Mechanical engineers integrate Clean-In-Place (CIP) and Steam-In-Place (SIP) systems, which are essential for maintaining sterile conditions between batches. These systems allow automated cleaning and sterilization of the vessel and piping without disassembly, reducing downtime and contamination risk.

Further, mechanical engineers design user-friendly access points for inspection, sampling, and maintenance. Safety is also paramount—they ensure that the system meets all applicable pressure vessel regulations and industry standards, incorporating features such as pressure relief valves, rupture disks, and instrumentation for real-time monitoring.

In essence, mechanical engineering provides the robust, durable, and sanitary infrastructure that enables reliable and reproducible fermentation processes on an industrial scale.

5. Economic and Costing Analysis

Economic analysis is a cornerstone of fermenter design, particularly at the industrial scale where capital investment and operating expenses are significant. The costing personnel or industrial economists perform comprehensive feasibility studies to determine whether the fermenter design is economically viable and aligns with the long-term financial objectives of the project. Their evaluation encompasses several critical aspects, including initial capital expenditure (CAPEX), operating expenses (OPEX), energy requirements, maintenance frequency and cost, equipment depreciation over time, labor costs, and the projected return on investment (ROI).

In practice, fermenter-related expenditures do not end at the point of procurement. The total cost of ownership must be considered, which includes installation, integration into existing production lines, utility consumption (electricity, steam, water), spare parts availability, downtime risks, and process optimization potential. Costing personnel also assess the financial implications of process control systems, automation, and sensor integration, weighing the benefits of long-term savings against higher initial costs.

Errors, delays, or inefficiencies in fermenter design can lead to substantial financial consequences, including production losses, increased waste generation, regulatory non-compliance penalties, and unplanned equipment replacement. As such, economic analysts work closely with engineers, microbiologists, and procurement teams to ensure that all design elements contribute to cost-effectiveness without compromising process safety, sterility, or operational reliability.

Furthermore, these analysts often evaluate alternative configurations and materials of construction, such as comparing stainless steel grades or considering the use of modular or prefabricated systems. They perform sensitivity analyses to identify cost drivers and assess the financial impact of potential process changes or scale-ups.

In today’s competitive biotechnology and biomanufacturing industries, achieving a favorable balance between performance, flexibility, and affordability is essential. Costing analysis thus plays a critical strategic role—not only in approving a given fermenter design but also in determining its scalability, sustainability, and economic resilience over the entire lifecycle of the bioprocess. Their insights ensure that investments in fermentation infrastructure deliver maximum value with minimal financial risk.

Key Factors to Consider in the Design and Construction of Fermenters

Given the complex nature of fermentation processes, a wide array of factors must be considered when designing and constructing fermenters. These include:

1. Material of Construction

The material selected for constructing a fermenter plays a crucial role in determining its durability, chemical compatibility, resistance to corrosion, and ability to maintain aseptic conditions. In industrial and laboratory-scale fermentation, 316L stainless steel is the industry standard due to its superior resistance to rust, chemical inertness, and robustness under repeated sterilization cycles. This high-grade alloy resists pitting and crevice corrosion, especially in chloride-containing media, and it maintains its integrity even under high temperatures and pressures.

Moreover, the internal surfaces of the fermenter must be mechanically polished and electropolished to achieve a smooth, non-porous finish. Such surface treatment reduces the risk of microbial adhesion, biofilm formation, and product contamination, which is especially important in the production of pharmaceuticals and food-grade products. The design must avoid crevices and dead legs where cleaning or sterilization might be ineffective.

Welded joints are preferred over flanged or threaded connections, as they provide a continuous and sealed surface, reducing potential points of contamination or leakage. Proper weld finishing and inspection are vital to maintain vessel integrity and hygiene.

While stainless steel is dominant in large-scale operations, borosilicate glass and high-grade plastic fermenters are commonly used in research, educational, or small-scale biotech applications. These allow visual monitoring of the fermentation process and are generally easier to handle. However, they are limited by their susceptibility to physical damage and chemical incompatibilities with certain solvents or sterilizing agents.

2. Aseptic Operation

Aseptic operation is a foundational requirement in fermentation to prevent microbial contamination and ensure product consistency. The fermenter must be designed to allow closed-system processing from inoculation through harvesting. All ports and connections should be fitted with sterilizable filters or seals, often using steam-in-place (SIP) technology to sterilize the vessel and associated lines without dismantling the equipment.

Key features supporting aseptic conditions include sterile sampling ports, automated valves, and connections for sterile nutrient addition. The inoculation port should permit the introduction of microbial culture without exposure to the external environment. Similarly, product removal must be achieved without introducing contaminants, which requires sterile harvest lines and holding tanks.

Any breach in sterility during extended fermentation runs, particularly in pharmaceutical or high-value biotech processes, can lead to batch failure and significant financial loss. Therefore, pressure relief valves, sterile filters, and condensate traps are included in the design to maintain internal overpressure and sterility barriers.

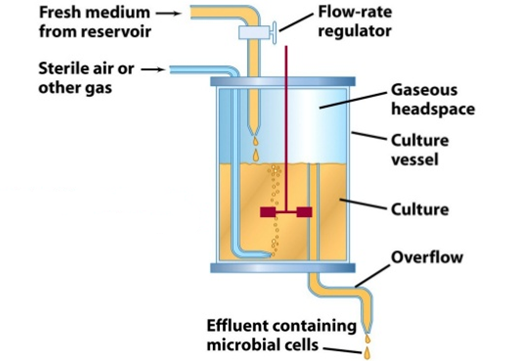

3. Agitation and Aeration Systems

Efficient mixing and aeration are critical for maintaining uniform environmental conditions within the fermenter. Agitation ensures homogeneous distribution of nutrients, oxygen, pH, and temperature, while also suspending microbial cells and preventing sedimentation. The agitator system typically includes axial or radial flow impellers, which are selected based on the nature of the fermentation—whether it is shear-sensitive (e.g., mammalian cells) or shear-tolerant (e.g., bacterial cultures).

Baffles are often installed vertically along the inner wall of the fermenter to disrupt vortex formation and enhance mixing efficiency. However, excessive agitation can result in shear stress, damaging delicate cells or enzymes. Therefore, impeller speed, design, and position must be carefully optimized.

For aerobic fermentation, aeration systems play a key role. Sterile air or oxygen is introduced via spargers—devices that disperse gas in fine bubbles, maximizing the gas-liquid mass transfer. The efficiency of oxygen transfer is quantified by parameters such as the oxygen transfer rate (OTR) and the volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient (kLa), which must be maximized without causing excessive foaming or stripping of volatile products.

4. Temperature Control

Temperature is a critical parameter influencing microbial metabolism, enzyme activity, and overall product yield. Most fermenters are equipped with cooling jackets, internal coils, or external heat exchangers to maintain a constant, optimal temperature throughout the process. These systems are integrated with thermocouples or resistance temperature detectors (RTDs) for real-time temperature monitoring and control.

In large-scale fermenters, microbial metabolic heat can significantly raise the temperature, requiring rapid and efficient heat removal. Failure to manage temperature properly can lead to enzyme denaturation, cell death, or altered product formation pathways.

5. pH Control

Maintaining an appropriate pH range is essential for cell viability and product formation. Fermenters are equipped with pH probes and automated dosing systems that can add acid or base to counteract changes in the medium’s pH during fermentation. Real-time monitoring and feedback control allow dynamic adjustments, especially important in processes where even slight pH deviations can alter product yield or quality.

In certain fermentations, metabolic by-products such as organic acids or ammonia can significantly shift the pH, necessitating continuous control. Some advanced systems integrate software algorithms to anticipate and correct pH drift, improving process efficiency and reducing operator intervention.

6. Foam Control

Foam formation is a common and often unavoidable challenge during aerobic fermentation, particularly under high-aeration and high-agitation conditions where gas-liquid interfaces are constantly being disrupted. Excessive foaming poses several risks: it can cause overflow, lead to contamination if foam escapes the sterile boundary, interfere with sensors, and result in loss of valuable product. To address this, fermenters should be equipped with integrated foam control mechanisms. These typically include foam sensors that detect the presence of foam and automatically trigger antifoam dosing systems to inject defoaming agents in precise amounts. Overuse of antifoams, however, can adversely affect oxygen transfer and downstream processing, so dosing must be tightly regulated. In some cases, mechanical foam breakers—such as rotating blades or deflector plates—are installed within the headspace to physically disrupt foam formation without the need for chemical additives.

7. Ease of Cleaning and Maintenance

Maintaining sterility and hygiene is critical in fermentation, especially in multi-batch or multi-product facilities. Frequent and effective cleaning minimizes the risk of cross-contamination and ensures consistent product quality. Modern fermenter design must incorporate clean-in-place (CIP) systems that allow internal surfaces to be cleaned automatically without dismantling equipment. These systems typically use a sequence of cleaning solutions, rinsing water, and sterilants circulated at specified flow rates and temperatures. Additionally, access points such as manways, sight glasses, and sample ports should be ergonomically designed to allow manual inspection, cleaning, and maintenance when necessary. Smooth interior surfaces, rounded corners, and the absence of dead zones further support easy and thorough cleaning. CIP validation is especially important in pharmaceutical and food-grade fermentations, where regulatory compliance is mandatory.

8. Scale and Flexibility

Scalability is a fundamental consideration in fermenter design. Laboratory-scale fermenters (1–10 L) are used for process development, pilot-scale units (10–1,000 L) for optimization, and industrial-scale systems (1,000–500,000 L or more) for full-scale production. A well-designed fermenter should enable seamless scale-up or scale-down without significantly altering critical hydrodynamic parameters such as mixing time, shear forces, and oxygen transfer rates. Achieving geometric and dynamic similarity ensures consistent microbial behavior across scales. In addition, flexibility in design is vital for facilities handling multiple processes or products. This includes compatibility with a wide range of microorganisms (bacteria, yeast, fungi, or mammalian cells) and substrates (synthetic or natural media), as well as modular features like interchangeable impellers, adjustable sparger configurations, and programmable control systems.

9. Evaporation Control

Evaporation is a significant concern during extended fermentations, especially under high-temperature or high-aeration conditions. Loss of water and volatile compounds (such as alcohols, organic acids, or aroma molecules) can alter the medium’s concentration, pH, osmotic balance, and product yield. To mitigate this, fermenters should be designed to minimize headspace volume and should include features such as reflux condensers that capture evaporated vapors and return them as condensate. Humidity control systems may also be employed to maintain the moisture balance of incoming air. In temperature-sensitive processes, jacketed vessels and thermal insulation can help reduce heat-induced evaporation. Proper evaporation management not only maintains fermentation consistency but also improves solvent and energy efficiency.

10. Energy Efficiency

Energy consumption in fermentation operations primarily stems from agitation, aeration, temperature regulation, and sterilization. As energy costs rise and sustainability becomes a global priority, the energy efficiency of fermenters has become increasingly important. Design elements that contribute to reduced energy use include efficient impeller designs (e.g., Rushton turbines or axial flow impellers), optimized baffle placement to improve mixing without excessive power input, and high-efficiency motors with variable frequency drives (VFDs). Thermal energy recovery systems, such as heat exchangers that reuse waste heat for preheating, also help in reducing overall consumption. Selecting materials with good thermal conductivity, such as stainless steel, supports faster heating/cooling and less energy waste.

11. Process Monitoring and Automation

Modern fermentation requires precise control over environmental and process parameters such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), agitation speed, aeration rate, and nutrient concentration. To achieve this, fermenters are now equipped with an array of inline sensors, automated control loops, and digital interfaces. These tools allow for real-time monitoring and rapid adjustments, improving batch consistency and reducing manual errors. Integration with Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems or Distributed Control Systems (DCS) enables centralized data logging, remote access, alarm management, and predictive maintenance. Advanced software tools also support modeling, simulation, and optimization of fermentation kinetics. Ultimately, automation enhances reproducibility, reduces labor intensity, and ensures compliance with industry standards and quality control protocols.

Cost Implications and Strategic Design Choices

Cost considerations in fermenter design extend well beyond the initial capital investment. While the purchase price of the equipment is often the most visible cost, it represents only a fraction of the total life-cycle cost. A comprehensive cost analysis must include procurement, installation, commissioning, energy and utility consumption, routine maintenance, unplanned repairs, potential downtime, and eventual decommissioning. Neglecting any of these components may lead to underestimated budgets and poor long-term performance. For instance, a poorly designed fermenter that fails to meet key process parameters—such as mixing efficiency, aeration requirements, or temperature control—can result in batch failures, increased contamination risks, compromised product yields, and ultimately, costly process interruptions and complete system overhauls.

Strategic design choices play a pivotal role in optimizing both performance and economic viability. Opting for modular construction allows for flexible scaling and easier upgrades, while standardizing parts and components simplifies maintenance, reduces inventory needs, and minimizes supply chain delays. Integrating energy-efficient motors and variable frequency drives can reduce power consumption significantly over the system’s lifespan. Similarly, incorporating process automation and advanced control systems may raise initial costs but enhance process reliability, reduce labor demands, and enable real-time monitoring for better decision-making.

Employing lean construction principles—such as reducing waste, improving workflow, and enhancing coordination—can further reduce installation time and associated costs. Value engineering techniques help identify design elements that can be optimized or replaced without compromising functionality or safety. By carefully evaluating the trade-offs between initial expenditure and long-term benefits, engineers can design fermenters that are not only cost-effective but also robust, scalable, and aligned with the specific needs of the bioprocess. Thus, a strategic and holistic approach to cost in fermenter design ensures sustainable operation and return on investment over the equipment’s useful life.

Conclusion

The design and construction of fermenters represent a convergence of biology, chemistry, engineering, and economics. Each discipline plays a critical role in ensuring that the final fermenter is not only fit for purpose but also economically sustainable. A fermenter that fails to support the biological requirements of the organism or process parameters will not only result in poor yields but also waste capital and operational resources.

To avoid such pitfalls, all critical factors—including material selection, sterility, agitation, aeration, temperature and pH control, scale-up compatibility, and cost-effectiveness—must be systematically addressed. Only then can the fermenter fulfill its function as the heart of an industrial bioprocess.

Ultimately, an effective fermenter is one that maximizes microbial productivity while minimizing energy, time, and financial inputs. Its design is not merely a technical task but a strategic investment in the success and profitability of industrial biotechnology.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This process is commonly facilitated by a GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) officer or a Quality manager. He/she ensures that the fermenter meets the required design qualifications and further establish the installation -, operational and functional qualification of the fermenter.

correct