Introduction

Fermentation stands as a fundamental and versatile process across multiple scientific and industrial disciplines, including biotechnology, applied microbiology, pharmaceuticals, food and beverage production, and environmental engineering. Central to this process is the fermenter—often interchangeably referred to as a bioreactor—a highly engineered vessel designed to cultivate microorganisms under tightly controlled environmental conditions. These microorganisms, which can include bacteria, yeasts, molds, filamentous fungi, and certain microalgae, are exploited for their remarkable biochemical capabilities to convert substrates into valuable products.

The fermenter’s role is critical in facilitating large-scale fermentation processes by providing and maintaining optimal conditions such as temperature, pH, oxygen concentration, nutrient availability, and mixing. These parameters must be finely tuned and continuously monitored to ensure the microorganisms thrive and efficiently produce desired metabolites, whether that be antibiotics, enzymes, biofuels, organic acids, fermented foods and beverages, or biomass for various industrial uses.

The significance of fermentation and fermenters extends beyond mere cultivation; they embody a convergence of engineering, microbiology, and process control. The ability to scale up from laboratory flask cultures to industrial-scale production hinges on the fermenter’s design and operational precision. Factors such as vessel geometry, agitation mechanisms, aeration systems, sensor integration, and control algorithms all influence fermentation outcomes.

This comprehensive treatise delves into the fundamental design considerations and operational strategies of fermenters. It explores how fermenters create and maintain ideal microenvironments tailored for specific microbial populations, ultimately maximizing product yield, purity, and process efficiency. By understanding these principles, scientists and engineers can better harness fermentation’s full potential, advancing innovations in health, industry, and sustainability.

Defining the Fermenter and Its Role

What Is a Fermenter?

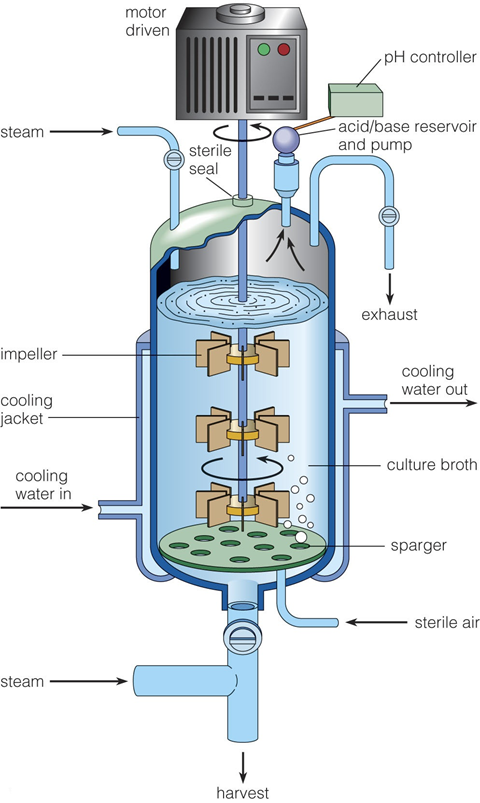

A fermenter, also commonly known as a bioreactor (Figure 1), is a specialized vessel or system designed specifically to cultivate microorganisms—such as bacteria, yeasts, and molds—under precisely controlled environmental conditions to facilitate and optimize the fermentation process. While the term “fermenter” traditionally refers to the physical container where fermentation occurs, “bioreactor” tends to have a broader meaning, encompassing not only microbial fermentation but also various biological reactions involving animal, plant, or even mammalian cells. However, in most industrial and research contexts, the distinction between these terms is minimal, and they are often used interchangeably to describe the same fundamental apparatus.

The primary role of a fermenter is to create and maintain an environment that supports the optimal growth and metabolic activity of the microorganisms involved. This involves regulating multiple factors simultaneously, including temperature, pH, oxygen levels (for aerobic organisms), nutrient availability, agitation, and pressure. Because microbial metabolism is extremely sensitive to even minor fluctuations in these parameters, precise control within the fermenter is essential for ensuring the consistency and efficiency of the fermentation process.

Fermenters are indispensable in many fields such as pharmaceuticals, food and beverage production, agriculture, and biofuel development. In these applications, microorganisms are harnessed to produce valuable metabolites, including antibiotics, enzymes, vitamins, organic acids, alcohols, and other bio-based chemicals. By providing a stable and optimized environment, fermenters enable these microbes to convert raw substrates into desired products at large scale, which is critical for commercial viability.

Moreover, the design of a fermenter allows for scalability and reproducibility—two vital attributes for industrial manufacturing. Laboratory-scale fermenters might handle volumes of a few liters for research and development, whereas industrial fermenters can operate at scales of tens to hundreds of thousands of liters, supporting mass production. By continuously monitoring and adjusting environmental conditions in real time, fermenters facilitate high yields and product quality while minimizing contamination risks and operational inefficiencies.

A fermenter functions as a carefully engineered microenvironment that balances physical, chemical, and biological parameters, enabling microorganisms to thrive and efficiently produce desired products. Its role extends beyond mere containment to actively optimizing the conditions that drive fermentation, thereby underpinning the success of microbial bioprocesses in various industrial applications.

Importance of Controlled Fermentation Environments

Fermentation is a complex biological process that relies heavily on maintaining precise environmental conditions tailored to the specific needs of the microorganisms involved. One of the most critical factors in fermentation is oxygen availability, as different microbes have distinct oxygen requirements. Aerobic fermentation processes demand a continuous supply of oxygen to sustain the growth and metabolic activities of organisms such as many bacteria and yeasts. To achieve this, fermenters are designed to provide adequate aeration and agitation, which help dissolve oxygen uniformly in the culture medium, ensuring that microorganisms receive sufficient oxygen for optimal growth and metabolite production. Agitation also assists in distributing nutrients and maintaining a consistent temperature throughout the vessel.

In contrast, anaerobic fermentation involves microbes that thrive in the complete absence of oxygen, such as certain Clostridium species. Fermenters used for anaerobic processes must be specially designed to exclude oxygen rigorously and maintain a reducing environment to prevent oxidative damage to the microbes. This often involves sealed vessels with controlled gas flows that replace oxygen with inert gases like nitrogen or carbon dioxide.

Beyond oxygen control, fermenters regulate other essential parameters that directly influence microbial metabolism and fermentation efficiency. Temperature is meticulously controlled because microbial enzymes, which drive biochemical reactions, have narrow optimal temperature ranges; deviations can slow metabolism or denature enzymes, reducing productivity. Similarly, pH must be maintained within specific limits since enzymatic activity and microbial growth are highly sensitive to changes in acidity or alkalinity. Nutrient supply is also carefully managed to provide the microbes with the building blocks for growth and product formation, while waste removal prevents the buildup of toxic byproducts that could inhibit fermentation.

Fermenters operate as sophisticated, dynamic systems that simultaneously monitor and adjust multiple environmental factors, creating an optimized habitat for microorganisms. This fine control is crucial not only for maximizing yield and product quality but also for ensuring reproducibility and scalability in industrial fermentation processes. In essence, controlled fermentation environments enable the transformation of microbial activity into efficient, predictable, and economically viable biotechnological production systems.

Design Considerations for Fermenters

Vessel Geometry and Material Selection

The design of a fermenter (Figure 2) vessel is critical to ensuring optimal microbial growth, efficient fermentation, and ease of operation. Industrial fermenters are predominantly constructed as cylindrical tanks featuring rounded bottoms and domed or hemispherical tops. This geometry is not arbitrary; it serves multiple crucial functions in the fermentation process. The cylindrical shape allows for uniform distribution of shear forces generated by agitation, enhancing effective mixing and preventing the formation of stagnant zones or “dead spots” where fluid flow is minimal or absent. These dead zones can lead to uneven nutrient and oxygen distribution, adversely affecting microbial growth and product yield. The rounded ends help to withstand internal pressures and reduce mechanical stress concentrations, thus improving the structural integrity of the vessel under varying operating conditions, including pressure fluctuations and thermal cycling during sterilization.

Material selection for fermenters is equally critical and is governed by a variety of stringent requirements tailored to the demanding environment of fermentation. The chosen material must be:

- Non-corrosive: Fermentation processes often produce acidic or otherwise reactive metabolites, and the vessel’s interior is frequently exposed to aggressive cleaning agents and sterilizing chemicals such as sodium hypochlorite, peracetic acid, or steam under pressure. Hence, materials must resist corrosion to maintain longevity and prevent contamination of the culture.

- Thermally stable: Industrial fermenters undergo sterilization cycles, commonly involving steam autoclaving at temperatures ranging from 120°C to 150°C or even higher. The vessel material must maintain mechanical integrity and resist deformation or degradation under these high-temperature conditions.

- Biocompatible: It is imperative that the fermenter material does not leach toxic ions, heavy metals, or other substances into the culture medium, as these could inhibit microbial growth or contaminate the final product, which is especially critical in pharmaceutical and food-grade fermentations.

Given these considerations, stainless steel alloys—particularly 316L stainless steel—are the industry standard for fermenter construction. The “L” denotes low carbon content, which enhances corrosion resistance after welding. Stainless steel 316L offers excellent durability, is resistant to pitting and crevice corrosion, and is readily cleanable to meet stringent hygiene requirements. Furthermore, it complies with regulatory standards such as those set by the FDA and other agencies for food, beverage, and pharmaceutical manufacturing. The smooth, polished surfaces of stainless steel also reduce microbial adherence and biofilm formation, facilitating sterilization and minimizing cross-contamination risks between batches.

The vessel’s geometry and choice of construction material are foundational elements that influence fermenter performance, operational reliability, and product quality, thereby dictating the success of large-scale fermentation operations.

Volume and Scale

Fermenters range widely in size, from small laboratory-scale units (1-20 liters) used for experimental and process optimization, to pilot-scale reactors (100-1,000 liters), up to full industrial production fermenters exceeding 100,000 liters in volume (Figure 3). The choice of scale depends on the intended application and production volume.

An important operational guideline is that only about 70-75% of the total fermenter volume is utilized as the working volume, leaving space for foam accumulation, gas headspace, and gas exhaust. This headspace prevents overflow and ensures proper gas exchange without spillage.

Sterility and Contamination Control

Since fermentations are often monocultures of specific microorganisms, maintaining sterility is paramount. Fermenters are designed with airtight seals, sterilizable inlet/outlet ports, and aseptic sampling systems to prevent contamination by unwanted microbes. Steam-in-place (SIP) and clean-in-place (CIP) systems are integral features in modern fermenters to allow automated cleaning and sterilization cycles without disassembly.

Core Components and Functional Systems of a Fermenter

The fermenter’s design incorporates multiple subsystems that collectively maintain and monitor the growth environment:

1. Temperature Control System

Microbial activity is temperature-dependent, with most microbes exhibiting optimal growth within a defined temperature range (mesophiles: ~25-40°C, thermophiles: >45°C, psychrophiles: <20°C). To maintain this:

- Heating jackets or coils surround the fermenter, circulating hot water or steam.

- Cooling jackets or internal cooling coils circulate cold water or refrigerants to dissipate metabolic heat generated by microbial activity or external heating.

- Automated temperature sensors and controllers modulate these heating/cooling systems to maintain precise thermal regulation, often within ±0.1°C accuracy.

2. Aeration and Gas Supply

For aerobic fermentations, oxygen supply is critical:

- Air or pure oxygen is supplied through spargers—fine perforated pipes or diffusers at the fermenter base—to create fine bubbles maximizing gas-liquid surface area.

- Air flow rates are controlled using mass flow controllers or rotameters.

- For anaerobic fermentations, the gas supply system can provide nitrogen, carbon dioxide, or other inert gases to purge oxygen.

3. Agitation System

Agitation ensures homogeneity of the culture:

- Impellers or stirrers, driven by electric motors through shafts sealed with sterile mechanical seals, keep the broth well mixed.

- Different impeller designs (Rushton turbines, marine impellers, pitched blades) are selected based on fluid viscosity and oxygen transfer requirements.

- Agitation improves nutrient distribution, temperature uniformity, and oxygen dissolution, while preventing sedimentation of cells or substrate.

4. pH Control

pH affects enzyme activity, membrane transport, and overall cell viability:

- pH sensors continuously monitor broth pH.

- Acid or base (e.g., HCl, NaOH) solutions are automatically dosed through controlled pumps to maintain the setpoint.

5. Foam Control

Foaming is common due to proteinaceous media and gas sparging:

- Antifoam agents can be added automatically or manually.

- Mechanical foam breakers or exhaust condensers with foam traps prevent foam overflow.

6. Nutrient and Substrate Feed Systems

- In batch fermentations, all nutrients are supplied initially.

- In fed-batch or continuous fermentations, feed lines supply substrates (carbon sources, nitrogen sources, vitamins) over time to sustain growth or metabolite production without substrate inhibition.

7. Product Harvesting and Waste Removal

- Outlets allow withdrawal of culture broth, biomass, or metabolites.

- In some designs, continuous removal of product and addition of fresh medium occur simultaneously (continuous fermentation).

8. Instrumentation and Automation

Modern fermenters integrate computerized control systems with sensors for:

- Temperature

- pH

- Dissolved oxygen (DO)

- Redox potential

- Biomass concentration (using optical sensors or capacitance probes)

- Off-gas analysis (CO₂, O₂)

Automation facilitates real-time process monitoring, feedback control, data logging, and remote operation, improving reproducibility and efficiency.

Types of Fermenters and Their Operational Modes

Batch Fermentation

The simplest mode where all ingredients are added at the start, and fermentation proceeds until substrate depletion or product accumulation limits growth. No additions or removals occur during fermentation except for aeration and agitation.

Fed-Batch Fermentation

Substrates are added incrementally to prevent substrate inhibition or catabolite repression, allowing higher cell densities and product titers.

Continuous Fermentation

Fresh medium is continuously fed, and culture broth is simultaneously removed at the same rate to maintain steady-state conditions, enabling long-term operation with constant product quality.

Specialized Fermenters

- Stirred Tank Reactors (STRs): Most common, versatile, and can handle aerobic or anaerobic processes by controlling oxygen supply.

- Air-lift Reactors: Use gas bubbles to circulate medium without mechanical agitation, reducing shear stress.

- Fluidized Bed Reactors: Immobilize cells on carriers for high-density cultivation.

- Packed Bed Reactors: Cells or enzymes are fixed on solid supports; substrate flows over.

- Photobioreactors: Designed for photosynthetic organisms, incorporating light supply.

Operational Parameters Critical to Fermenter Performance

Temperature

Optimal growth temperature varies widely. Maintaining constant temperature prevents metabolic stress and ensures enzyme efficiency. Overheating due to metabolic heat generation or mechanical agitation must be dissipated promptly.

pH

Most industrial fermentations maintain pH between 5-7, but extremophiles may require more acidic or alkaline conditions. pH fluctuations can alter enzyme activities and cell membrane permeability, influencing growth and product formation.

Dissolved Oxygen (DO)

Aerobic microbes require oxygen levels typically maintained above 20-40% saturation. DO sensors measure oxygen dissolved in the broth, and aeration/agitation are adjusted accordingly. Low DO can limit growth; excess oxygen may cause oxidative stress.

Agitation Speed

Determines shear forces and oxygen transfer rate. Too high agitation can damage shear-sensitive cells; too low leads to poor mixing and oxygen limitation.

Nutrient Concentration

Balanced supply avoids nutrient limitation or toxicity. In fed-batch systems, feeding strategies optimize nutrient delivery for maximal productivity.

Pressure

Increased pressure can enhance gas solubility, especially oxygen. Some fermenters operate under slight positive pressure to reduce contamination risk.

Challenges in Fermenter Design and Operation

Scale-Up

Processes developed in small laboratory fermenters face challenges during scale-up, including:

- Maintaining oxygen transfer efficiency.

- Uniform mixing in larger volumes.

- Heat removal due to increased metabolic heat.

- Sterilization complexity.

- Controlling gradients (pH, nutrients, temperature) that may develop in large tanks.

Scale-up often follows geometric similarity, constant power input per unit volume, or oxygen transfer criteria but requires empirical adjustments.

Contamination

Microbial contamination can ruin entire batches. Ensuring aseptic conditions and rapid sterilization cycles is critical. Cross-contamination in continuous systems is especially challenging.

Foam Control

Excess foam can cause operational problems such as blocking exhaust lines or causing contamination. Mechanical foam breakers and antifoaming agents mitigate foam but can affect downstream processing.

Recent Advances and Future Directions in Fermenter Technology

The field of fermenter technology is rapidly evolving, driven by the need for higher efficiency, greater precision, and sustainable production in biotechnology and industrial fermentation processes. Innovations in materials, automation, and design are transforming fermenters from simple vessels into highly sophisticated bioprocessing systems. Here we explore some of the most significant recent advances and potential future directions shaping the landscape of fermenter technology.

Smart Fermenters and Automation

One of the most transformative trends in fermenter design is the integration of advanced sensors coupled with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms. Modern fermenters now incorporate real-time monitoring systems capable of tracking multiple parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, biomass concentration, and metabolite levels continuously. AI-driven analytics process this complex data to predict microbial behavior and adjust operational parameters dynamically. This predictive monitoring enables adaptive control strategies that optimize fermentation conditions, leading to enhanced product yield, improved reproducibility, and reduced downtime caused by unexpected process deviations. Automation also minimizes human intervention, lowering the risk of contamination and operator error. As these “smart fermenters” evolve, they are expected to integrate further with cloud computing and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms, allowing remote supervision and control of fermentation processes worldwide.

Single-Use Bioreactors

Single-use or disposable bioreactors represent a major shift in bioprocessing, especially in pharmaceutical manufacturing and cell culture industries. These systems come pre-sterilized and are designed for one-time use, eliminating the time-consuming and costly cleaning and sterilization steps traditionally associated with stainless steel fermenters. This significantly reduces turnaround time between production batches and decreases the risk of cross-contamination. Single-use bioreactors are particularly advantageous for small-to-medium scale productions, personalized medicine, and rapidly changing product pipelines. Advances in polymer science and material engineering continue to improve their chemical resistance, mechanical stability, and gas transfer capabilities, making them increasingly viable for a broad range of fermentation applications.

3D-Printed Bioreactors

The advent of 3D printing technology is opening new frontiers in fermenter design customization. By enabling rapid prototyping and manufacturing of complex geometries that were previously difficult or impossible to achieve, 3D-printed bioreactors can be tailored precisely to the needs of specific microorganisms or fermentation processes. This includes optimizing mixing patterns, enhancing mass and heat transfer, and integrating novel sensor placements for improved process monitoring. Additionally, 3D printing allows for cost-effective small-batch production of specialized fermenters, fostering innovation and experimentation in research and development settings.

Environmental Sustainability

Sustainability considerations are becoming increasingly important in fermenter design. Modern fermenters are being engineered to maximize energy efficiency by improving heat exchange systems and reducing power consumption during agitation and aeration. Water usage is minimized through closed-loop recycling of process streams and the adoption of water-saving cleaning protocols. Furthermore, advances in materials enable longer equipment lifespans and facilitate recycling or repurposing of components. These efforts contribute to greener biotechnological manufacturing, aligning fermentation processes with global sustainability goals and regulatory demands.

Conclusion

The fermenter is a pivotal element in the biotechnology and industrial microbiology landscape, serving as the controlled environment where microorganisms convert substrates into valuable products. Its design and operation integrate principles of engineering, microbiology, chemistry, and process control to meet the stringent demands of modern bioproduction.

From material selection and vessel geometry to sophisticated control systems for temperature, pH, oxygen, and nutrient supply, each aspect of fermenter design profoundly influences fermentation efficiency and product quality. Understanding the complexities of fermenter operation is essential for optimizing yields, scaling processes from lab to industry, and driving innovation in microbial biotechnology.

As fermentation technology advances with automation, smart sensors, and novel materials, fermenters will continue to evolve as highly optimized bioprocessing platforms, underpinning the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, food ingredients, and many other bioproducts essential to a sustainable bioeconomy.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.