Blood culture is the most important diagnostic method for detecting and diagnosing bacteraemia (presence of bacteria in blood) and fungimia (i.e. presence of pathogenic fungi in blood) in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Blood specimen required for blood culture technique should be collected from the patient prior to antibiotic therapy in order to increase the sensitivity of the test.

This is important because prior antibiotic therapy before the drawing of blood for blood culture reduces the effectiveness of the test – since antimicrobial therapy may reduce the level of microbial load in the sample in vivo. It is therefore a general rule to collect blood samples for blood culture techniques before the initiation of antibiotic therapy.

However, this is not always the case especially in critically ill patients due to high rate of mortality associated with delayed treatment. In such patients, blood can be drawn prior to or after antibiotic therapy in order to avoid any fatality. Nevertheless, most blood culture media contain substances that help to inhibit the onslaught of antibiotics present in the collected blood for blood culture analysis.

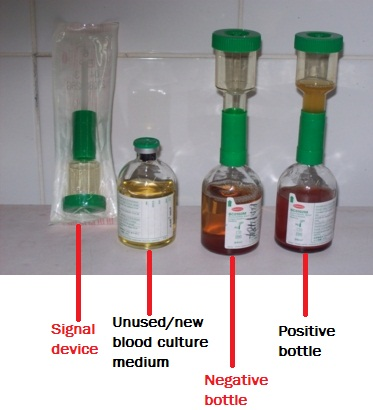

Different blood culture medium exist commercially for the culture of blood specimens in the hospital and/or research laboratory; and they each support the growth of anaerobic bacteria, facultative organisms and aerobic bacteria. the Oxoid blood culture medium is a typical example of blood culture medium used universally for the culture of blood samples (Figure 1).

AIM: To isolate and identify the presence of pathogenic bacteria in blood specimen as an aid in the diagnosis of bacteraemia and septicaemia.

MATERIAL/APPARATUS: Blood specimen (about 10 ml), incubator, blood culture medium (e.g. Oxoid signal blood culture system and medium), blood agar (BA), chocolate agar (CA), cystein lactose – electrolyte deficient (CLED) agar, inoculating loop, Bunsen burner, grease pencil, 70% ethanol, cotton wool. It should be noted that there are several blood culture medium available for blood culture. The type of blood culture medium used is left to the discretion of the researcher and the type of bacteria being isolated (anaerobic, aerobic or facultative organisms).

METHOD/PROCEDURE FOR BLOOD CULTURE

- Remove the protective cover from the top of the blood culture bottle.

- Clean/wipe the top of the blood culture bottle with a cotton swab of ethanol.

- Aseptically dispense the 10 ml of blood into the blood culture medium blood.

- Clean the top of the blood culture bottle medium with cotton swab of ethanol after dispensing or inoculating the blood specimen.

- Shake the blood culture bottle to mix the blood sample with the broth.

- Replace the culture signal device above the top of the blood culture bottle.

- Label the blood culture bottle with the patient’s name and number using a grease pencil.

- Incubate the inoculated blood culture bottle in the incubator at 37oC for 7 days.

- Examine the incubated blood culture bottle at intervals. Terminal subcultures can also be done before the 7 days elapses using CA, CLED, and BA agar plates.

- Perform a Gram stain to determine if the bacteria are either Gram positive or Gram negative.

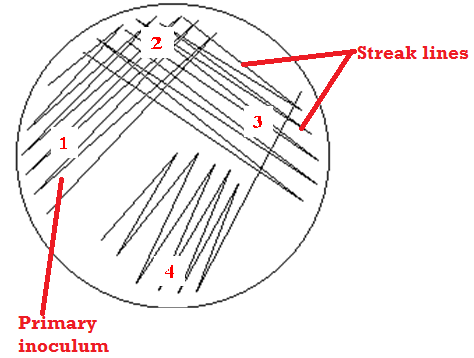

- Then aseptically subculture an aliquot (the contents of the growth indicator device of the blood culture bottle) on relevant agar plates (e.g. CLED, BA, and CA) to look out for bacterial growth (Figure 2).

- Incubate the CLED and BA plates in the incubator at 37oC overnight.

- Incubate the CA plate in a carbon dioxide enriched atmosphere (e.g. anaerobic jar). The reason for this is to provide about 5 – 10 % CO2 for the luxuriant growth of anaerobes present in the blood specimen.

- Examine plates for bacterial growth after incubation.

- Subculture the isolated organisms onto freshly prepared culture media plates (e.g. CA and BA) for the isolation of pure cultures.

- Conduct biochemical tests and gram staining, and Perform antimicrobial susceptibility test only when a pathogen is successfully isolated and identified.

REPORTING OF THE RESULT: Always report immediately a positive blood culture, and send a preliminary report of the stained smear and other useful test results to the physician in charge of the patient. This is very important as it is known that the blood is a sterile fluid that does not harbour microbes inclusive of a normal microbial flora unlike other parts of the human body like the skin and urinary tract system that are flooded with a wide variety of normal microbial flora. Presence of bacteria in the blood is indicative of a pathological/disease state. Report any pathogen that is isolated.

Bacteraemia is defined as the presence of bacteria in the blood. It is usually pathological (i.e. indicative of a serious disease) although transitory asymptomatic bacteraemia can occur during the course of many infections and after a surgical operation have been undertaken in a given patient. Bacteraemia usually occurs in such diseases as: typhoid fever, endocarditis, and brucellosis.

Septicaemia is defined as a severe life – threatening bacteraemia (i.e. heavy load of bacteria in the bloodstream). In septicaemic conditions, there is a large amount of bacteria in the blood, and these bacteria release toxins into the blood stream. These toxins trigger the production of cytokines, causing fever, low blood pressure, toxicity, and even collapse. A complication of septicemia is septic shock that may result in death if not managed well by healthcare professionals. Prompt treatment is essential in any septicaemic disease condition.

References

Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. World Health Organization (WHO), 1991. Available from WHO publications, 1211 Geneva, 27-Switzerland.

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th edition. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute of Health. HHS Publication No. (CDC) 21-1112.2009.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part I. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part 2. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Collins C.H, Lyne P.M, Grange J.M and Falkinham J.O (2004). Collins and Lyne’s Microbiological Methods. Eight edition. Arnold publishers, New York, USA.

Disinfection and Sterilization. (1993). Laboratory Biosafety Manual (2nd ed., pp. 60-70). Geneva: WHO.

Garcia L.S (2010). Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Garcia L.S (2014). Clinical Laboratory Management. First edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Fleming, D. O., Richardson, J. H., Tulis, J. I. and Vesley, D. (eds) (1995). Laboratory Safety: Principles and practice. Washington DC: ASM press.

Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. (2004). Practical Microbiology. S.Chand and Company LTD, New Delhi, India.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.