The term biogeochemical is derived from the combination of three distinct but interrelated words: bio, geo, and chemical. The prefix bio refers to life and encompasses all living organisms within the ecosystem, including humans, animals, plants, and microorganisms. The prefix geo relates to the Earth and geological processes such as rock formation, weathering, erosion, sedimentation, and soil development that occur within the Earth’s crust. The term chemical refers to the chemical elements and compounds, as well as the reactions and transformations they undergo within the environment. When combined, the term biogeochemical captures the integrated interactions among biological, geological, and chemical processes that regulate the movement and transformation of matter within the Earth system.

Biogeochemical cycling refers to the pathways through which chemical elements and compounds move continuously between living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the Earth. These cycles describe how essential nutrients and elements such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, oxygen, hydrogen, calcium, and water are circulated, transformed, stored, and reused within the environment. Biogeochemical cycles are fundamental natural processes that ensure the availability of life-supporting elements and maintain the stability and productivity of ecosystems. Without these cycles, essential nutrients would become depleted or accumulate to harmful levels, making the Earth incapable of sustaining life over long periods.

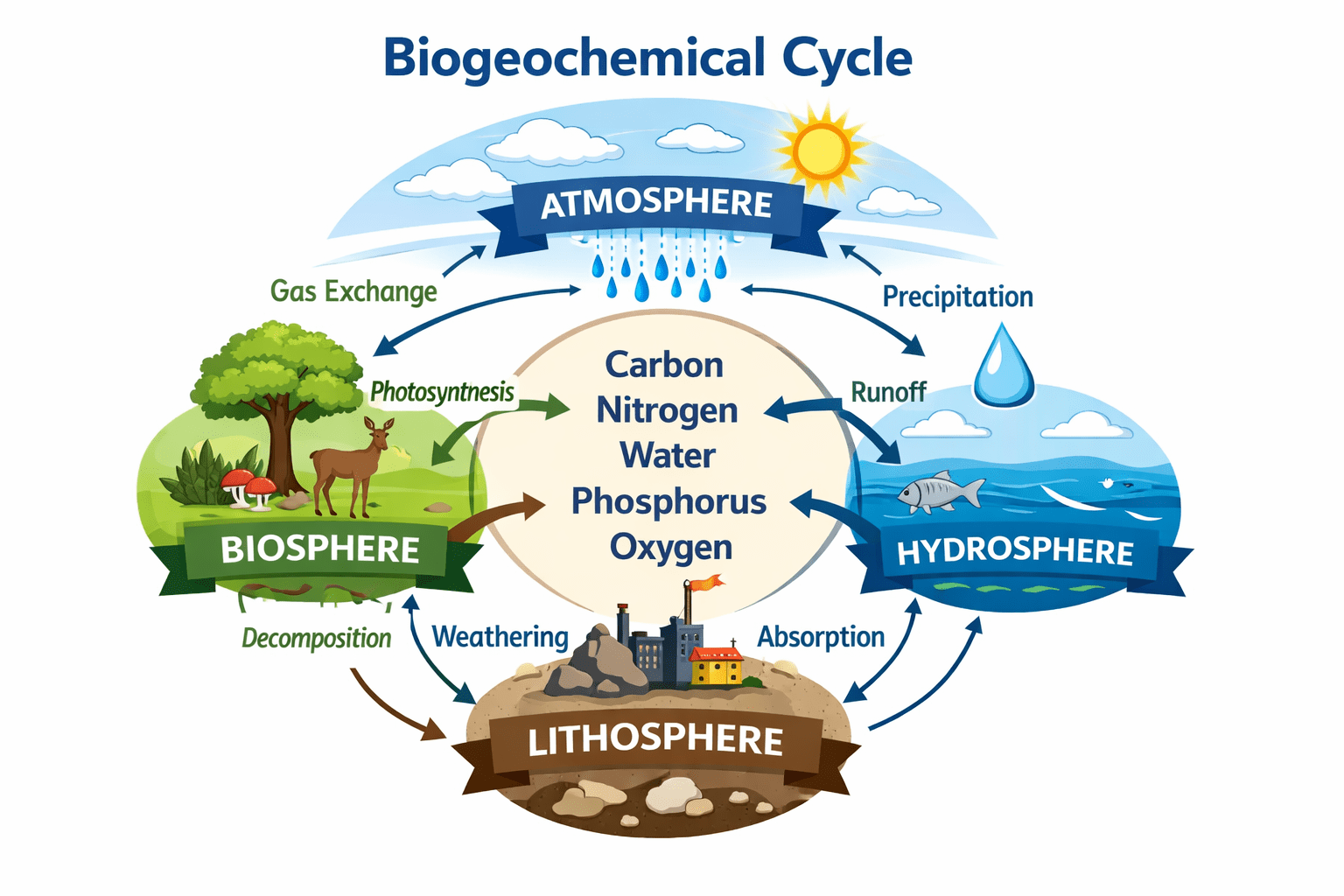

In essence, a biogeochemical cycle is any natural, recurring pathway by which elements essential to life are circulated through the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, and biosphere. These cycles operate continuously, allowing matter to be conserved and reused, even though energy flows through ecosystems in a largely one-way direction. The continuous recycling of matter distinguishes biogeochemical cycles from energy flow and underscores their central role in sustaining life on Earth.

Major Earth Systems Involved in Biogeochemical Cycling

Biogeochemical cycles operate through interactions among four major components, or spheres, of the Earth system. These spheres act as reservoirs or storage compartments for chemical elements and compounds, and the movement of matter between them drives nutrient cycling.

- The Biosphere

The biosphere comprises all living organisms on Earth, including plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. Living organisms play a central role in biogeochemical cycles because they assimilate chemical elements into their tissues, transform them through metabolic processes, and return them to the environment through respiration, excretion, and decomposition. For example, plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, animals obtain carbon by feeding on plants or other animals, and decomposers return carbon and nutrients to the soil and atmosphere when organisms die.

- The Lithosphere

The lithosphere includes the Earth’s crust and upper mantle and consists primarily of rocks, soils, minerals, and sediments. It serves as a major reservoir for many elements, particularly those involved in sedimentary cycles such as phosphorus, calcium, iron, and sulphur. Weathering of rocks releases these elements into the soil and water, where they become available for uptake by living organisms. Over geological time scales, elements can be buried in sediments and rocks, effectively removing them from active cycling.

- The Hydrosphere

The hydrosphere consists of all water bodies on Earth, including oceans, seas, rivers, lakes, groundwater, glaciers, and atmospheric moisture. Water acts as a medium for transporting dissolved nutrients and gases and plays a crucial role in nearly all biogeochemical cycles. Oceans, in particular, are major reservoirs for carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur and are integral to regulating global climate and nutrient availability.

- The Atmosphere

The atmosphere is the gaseous envelope surrounding the Earth and contains essential gases such as oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor. Many biogeochemical cycles have significant atmospheric components, especially those involving gaseous elements. The atmosphere serves as both a reservoir and a transport medium, allowing elements to be distributed across vast distances through wind and atmospheric circulation.

Together, these four spheres interact continuously, allowing chemical elements and compounds to move in a controlled and cyclical manner that supports ecological balance and life.

Macronutrients and Micronutrients in Biogeochemical Cycles

The chemical elements involved in biogeochemical cycles can be classified based on the quantity required by living organisms. These elements are broadly categorized into macronutrients and micronutrients.

Macronutrients are elements required in relatively large amounts by all forms of life. They form the basic structural and functional components of living cells and are essential for growth, metabolism, and reproduction. Major macronutrients include carbon (C), nitrogen (N), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), phosphorus (P), and sulphur (S). Carbon is the backbone of all organic molecules, nitrogen is a key component of proteins and nucleic acids, phosphorus is essential for energy transfer and genetic material, while oxygen and hydrogen are integral to water and many biochemical reactions.

Micronutrients, also known as trace elements, are required in much smaller quantities but are nonetheless vital for normal biological functioning. These elements often act as cofactors for enzymes and play important roles in metabolic regulation. Examples of micronutrients include iron, copper, zinc, manganese, molybdenum, and cobalt. Although required in small amounts, deficiencies or excesses of micronutrients can have significant ecological and physiological consequences.

The availability, movement, and transformation of both macronutrients and micronutrients are regulated by biogeochemical cycles, ensuring that organisms can access the nutrients they need for survival.

Processes Driving Biogeochemical Cycles

The movement of elements through the Earth system occurs through a combination of biological, physical, chemical, and anthropogenic (human-induced) processes.

Biological processes include photosynthesis, respiration, nitrogen fixation, assimilation, excretion, and decomposition. For instance, plants use carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis to produce organic matter, while animals release carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere through respiration. Microorganisms play especially critical roles by mediating transformations such as nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification.

Physical processes involve the movement of matter through non-biological means, such as diffusion, evaporation, precipitation, erosion, sedimentation, and ocean circulation. For example, carbon dioxide dissolves from the atmosphere into ocean water, and weathering processes release minerals from rocks into soils and waterways.

Chemical processes include oxidation-reduction reactions, dissolution, precipitation, and chemical bonding that alter the form and availability of elements. These reactions often determine whether an element is biologically accessible or locked in an unavailable form.

Human activities have become increasingly important drivers of biogeochemical cycles. Activities such as fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, industrial production, agriculture, mining, and waste disposal significantly alter the natural movement and balance of elements, often at rates far exceeding natural processes.

Classification of Biogeochemical Cycles

Biogeochemical cycles are commonly classified into gaseous cycles and sedimentary cycles, based on the primary reservoir in which the element is stored.

Gaseous cycles are those in which the major reservoirs of elements are the atmosphere or oceans. These cycles tend to operate relatively rapidly and include the carbon cycle, nitrogen cycle, oxygen cycle, and water (hydrological) cycle. Because the atmospheric reservoir is large and well-mixed, elements in gaseous cycles are often widely distributed across the globe.

Sedimentary cycles, in contrast, have their primary reservoirs in the Earth’s crust, rocks, and sediments. These cycles generally operate more slowly and include the phosphorus cycle, sulphur cycle, calcium cycle, and iron cycle. The availability of elements in sedimentary cycles is often limited by geological processes such as weathering and uplift, making these elements potential limiting factors in ecosystems.

Both types of cycles are interconnected, and changes in one cycle can influence others.

Importance of Biogeochemical Cycles to Ecosystem Stability

The chemical elements and compounds recycled through biogeochemical cycles serve as the currency of ecosystems. Living organisms continuously utilize these elements to meet their metabolic, structural, and developmental needs. As organisms grow, reproduce, and eventually die, the elements contained in their bodies must be returned to the environment to be reused by other organisms.

For example, oxygen is essential for aerobic respiration in most living organisms. Green plants produce oxygen as a by-product of photosynthesis, while animals and many microorganisms consume oxygen during respiration. If oxygen consumption were to exceed oxygen production over extended periods, atmospheric oxygen levels would decline, threatening the survival of aerobic life. However, through the operation of the oxygen cycle, atmospheric oxygen is maintained at a relatively stable concentration of about 20–21 percent, which is optimal for sustaining life.

Similar balancing mechanisms operate for other elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. These cycles ensure that elements are neither permanently lost nor excessively accumulated in any single compartment of the Earth system.

Biogeochemical Cycles as Closed Systems

Biogeochemical cycles function more like closed systems than open systems because matter is conserved and continuously reused. The products of one process often serve as substrates for another, creating a network of interconnected pathways. For example, carbon fixed by plants during photosynthesis becomes food for animals, is released as carbon dioxide during respiration, and can then be reused by plants.

The closed nature of these cycles allows ecosystems to maintain long-term stability and resilience. As long as the rates of input and output remain balanced, ecosystems can sustain life without depleting essential resources.

Human Impacts on Biogeochemical Cycles

One of the most significant challenges to the optimal functioning of biogeochemical cycles is the alteration caused by human activities. When essential elements are not available in the right amounts, at the right time, or in the right proportions, biogeochemical cycles become disrupted.

Human activities such as fossil fuel combustion have dramatically increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, intensifying the carbon cycle and contributing to global climate change. Similarly, the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers has altered the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, leading to nutrient pollution, eutrophication of water bodies, and loss of aquatic biodiversity.

Emissions from motor vehicles, industrial plants, deforestation, and biomass burning release large quantities of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and sulphur compounds into the atmosphere. These changes occur at a global scale and have far-reaching consequences for climate regulation, ecosystem productivity, and environmental quality.

Biogeochemical Cycles, Climate Change, and Sustainability

Altered biogeochemical cycles, combined with climate change, increase the vulnerability of ecosystems, biodiversity, food security, human health, and water quality. Excess nutrients in aquatic systems can cause eutrophication, leading to oxygen depletion and the collapse of fisheries. Climate-driven changes in temperature and precipitation can further modify nutrient cycling, creating feedback loops that exacerbate environmental degradation.

Understanding biogeochemical cycles is therefore critical for developing sustainable environmental management strategies. By studying how these cycles operate and how they respond to natural and human-induced changes, scientists can better predict environmental outcomes and design interventions to mitigate negative impacts.

Importantly, both natural and managed shifts in biogeochemical cycles can help limit the rate and severity of climate change. Practices such as reforestation, sustainable agriculture, wetland restoration, and improved nutrient management can enhance natural cycling processes and restore ecological balance.

Biogeochemical cycles are fundamental to the functioning of the Earth system and the sustenance of life on the planet. Through the continuous movement and transformation of essential elements among the biosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere, these cycles maintain the availability of nutrients, regulate environmental conditions, and support ecosystem stability. While natural processes have sustained these cycles for millions of years, human activities have increasingly disrupted them, posing significant challenges to environmental sustainability. A comprehensive understanding of biogeochemical cycles is therefore essential for addressing global environmental problems, protecting biodiversity, and ensuring a sustainable future for life on Earth.

References

Abrahams P.W (2006). Soil, geography and human disease: a critical review of the importance of medical cartography. Progress in Physical Geography, 30:490-512.

Ahring B.K, Angelidaki I and Johansen K (1992). Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci. Technol, 30, 241–249.

Andersson L and Rydberg L (1988). Trends in nutrient and oxygen conditions within the Kattegat: effects on local nutrient supply. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci, 26:559–579.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Pelczar M.J., Chan E.C.S. and Krieg N.R. (2003). Microbiology of Soil. Microbiology, 5th Edition. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, New Delhi, India.

Pepper I.L and Gerba C.P (2005). Environmental Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. Second Edition. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, USA.

Roberto P. Anitori (2012). Extremophiles: Microbiology and Biotechnology. First edition. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, England.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Sawyer C.N, McCarty P.L and Parkin G.F (2003). Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishers, New York, USA.

Ulrich A and Becker R (2006). Soil parent material is a key determinant of the bacterial community structure in arable soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 56(3):430–443.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.