Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a debilitating water-borne disease caused by parasitic blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma. It is recognized as one of the most important neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), second only to malaria in terms of parasitic disease burden worldwide. An estimated 200 million people are currently infected with schistosomiasis, and more than 700 million live at risk in endemic areas where safe water, sanitation, and health services are limited.

The life cycle of Schistosoma reflects its intimate connection to both human and environmental health. The parasites require freshwater snails as intermediate hosts, releasing free-swimming larvae (cercariae) that penetrate human skin during routine water contact. Once inside, adult worms take up residence in venous plexuses, producing eggs that are responsible for the disease’s major complications – chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and organ damage.

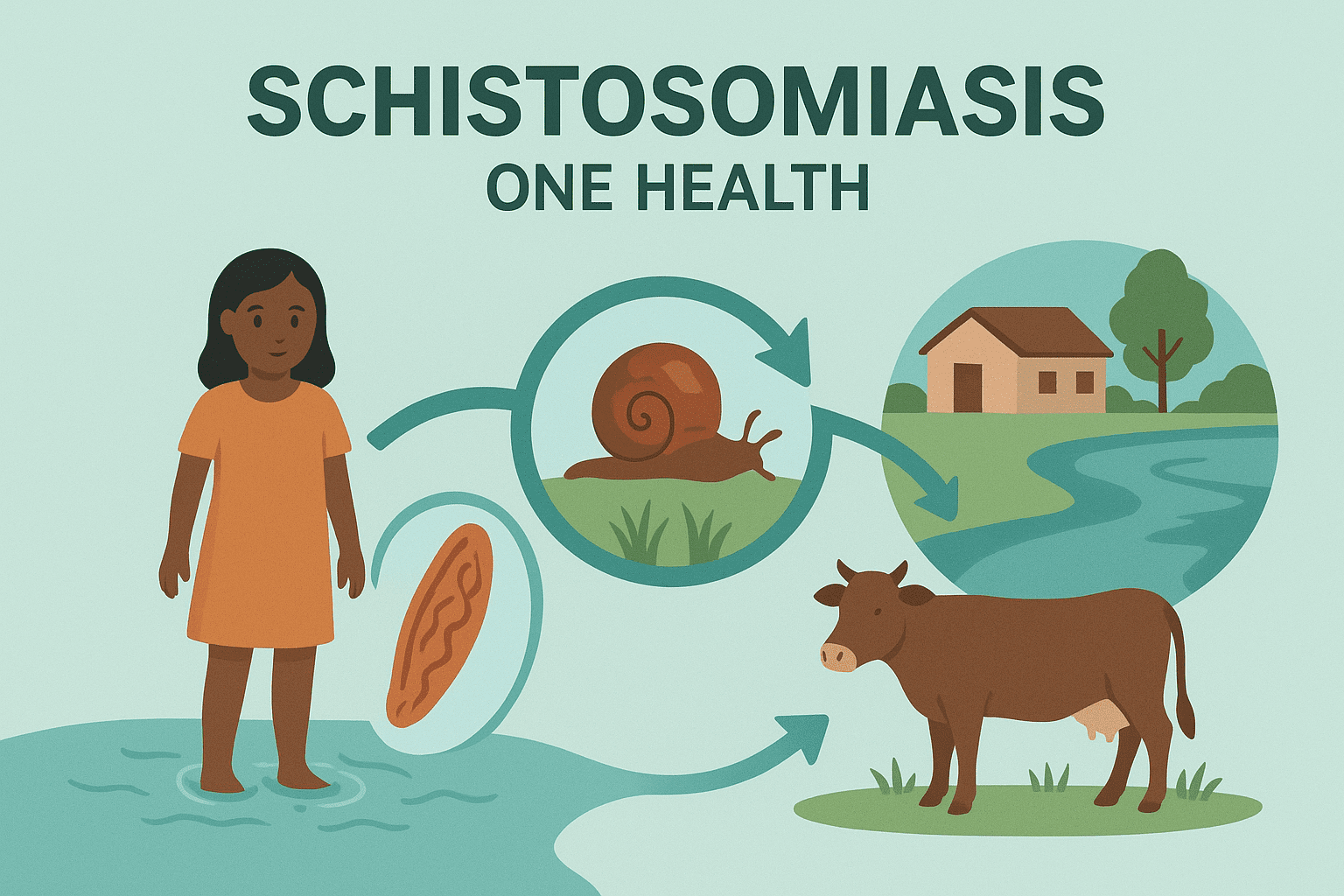

Schistosomiasis is not only a human health problem but also an ecological and social issue. Livestock and wildlife can serve as reservoirs for some species, irrigation and dam projects expand snail habitats, and poverty-driven reliance on contaminated water perpetuates transmission. This makes schistosomiasis a quintessential One Health challenge – its control requires coordinated efforts across human health, veterinary care, water management, and environmental stewardship.

Causative Species, Taxonomy, and Reservoirs

Schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) is a parasitic disease caused by blood-dwelling flukes of the genus Schistosoma (family Schistosomatidae). Unlike most trematodes, which are hermaphroditic, schistosomes are dioecious, with distinct male and female worms. The slender female resides within the gynecophoral canal of the thicker-bodied male, a unique adaptation that enables prolonged pairing, continuous egg laying, and sustained transmission within the host’s vascular system.

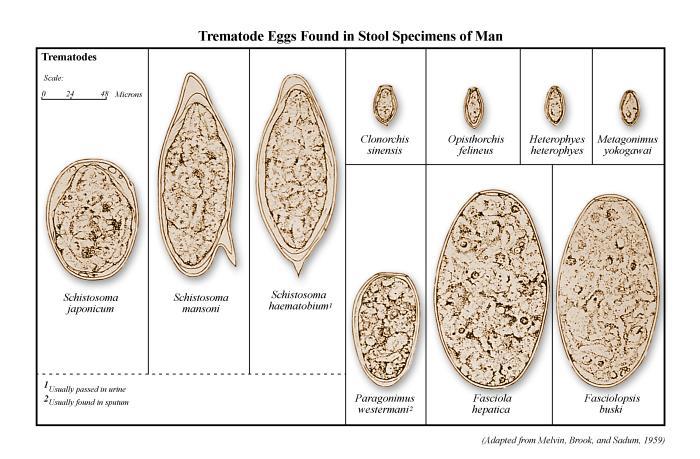

Six Schistosoma species are known to infect humans. The three most widespread are S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and S. japonicum, while S. mekongi, S. intercalatum, and S. guineensis have more restricted geographic distributions. Additionally, hybrid forms involving livestock schistosomes (e.g., S. haematobium × S. bovis, S. curassoni, S. mattheei) have occasionally been reported in humans.

Major human schistosomes

- Schistosoma haematobium

S. haematobium is the causative agent of urogenital schistosomiasis, a form of the disease that primarily affects the urinary tract and genital system. Adult worms localize in the venous plexus surrounding the bladder, and females release eggs that pass through the bladder wall to exit in urine. The eggs have a characteristic terminal spine, aiding microscopic identification. Clinical disease is marked by haematuria (blood in urine), dysuria, and progressive bladder pathology, with chronic infection increasing the risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. In women, egg deposition in the genital tract leads to female genital schistosomiasis, which can cause infertility, reproductive complications, and heightened vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections.

- Schistosoma mansoni

S. mansoni is the predominant cause of intestinal schistosomiasis in Africa and parts of South America. Adult worms inhabit the inferior mesenteric venules draining the large intestine. Eggs are deposited in the intestinal wall and excreted in feces. The eggs possess a prominent lateral spine. Chronic infections are characterized by intestinal inflammation, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, but the most serious complications occur in the liver. Egg-induced granulomatous inflammation within the periportal spaces of the liver leads to fibrosis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly, and, in severe cases, life-threatening variceal bleeding.

- Schistosoma japonicum

S. japonicum causes intestinal and hepatosplenic schistosomiasis and is primarily found in East and Southeast Asia. This species is considered the most pathogenic due to its high egg production rate and the small size of the eggs, which allows widespread dissemination in tissues. Adult worms inhabit the superior mesenteric veins of the small intestine, releasing rounded eggs with a small lateral spine that are shed in feces. Infections are associated with more severe hepatosplenic disease compared to S. mansoni, with extensive fibrosis and portal hypertension developing rapidly. Importantly, S. japonicum has a broad zoonotic potential. It infects a wide range of animal hosts, including cattle, water buffaloes, dogs, pigs, and various rodents. This extensive reservoir base makes control and elimination efforts particularly challenging in endemic regions.

Less common human schistosomes

Several other species can infect humans, though they have more restricted geographic distributions and contribute less to the global burden:

- Schistosoma mekongi is found in parts of the Mekong River basin in Cambodia and Laos. It resembles S. japonicum in morphology and pathogenicity but is geographically limited.

- Schistosoma intercalatum occurs mainly in Central and West Africa, causing intestinal schistosomiasis with eggs that feature a terminal spine, similar to S. haematobium, but with distinct morphological differences.

- Schistosoma guineensis has been described in parts of Central Africa and is closely related to S. intercalatum.

These species remain important for regional public health but are not globally widespread.

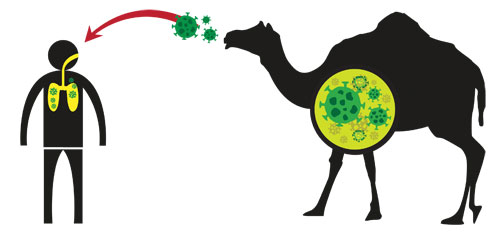

Animal reservoirs and zoonotic potential of schistosomes

The ecology of schistosomiasis highlights the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. While S. haematobium and S. mansoni are predominantly human parasites, S. japonicum is a classic example of a zoonotic parasite with a wide host range. Livestock such as cattle and water buffalo are especially important reservoirs, maintaining transmission in farming communities where humans and animals share freshwater resources. Rodents and domestic animals like dogs and pigs can also harbor infections, contributing to the persistence of transmission cycles even when human treatment programs achieve high coverage.

Emerging evidence suggests that hybridization between human and animal schistosome species may occur in areas where humans, livestock, and wildlife interact intensively. For example, cross-breeding events between S. haematobium and livestock schistosomes have been reported, creating hybrids that may alter host specificity, transmission dynamics, or drug susceptibility. Such genetic mixing complicates elimination strategies because it blurs the boundary between strictly human transmission cycles and zoonotic reservoirs.

Implications of Schistosoma diversity for control and elimination

The diversity of causative species, coupled with the role of animal reservoirs, has profound implications for schistosomiasis control. In areas where S. japonicum is endemic, controlling transmission requires not only mass drug administration to human populations but also veterinary interventions and improved water management. Treating livestock, modifying agricultural practices, and reducing animal contamination of water sources become necessary to break the cycle of infection.

Similarly, ecological modifications that affect snail habitats can shift transmission dynamics, sometimes reducing, but occasionally enhancing, parasite persistence.From a One Health perspective, schistosomiasis epitomizes the interconnectedness of human health, animal health, and ecosystems. Effective long-term control must address not only the human burden but also the roles of animal reservoirs and environmental factors that sustain the parasite’s life cycle. Strategies that ignore these broader dimensions risk temporary gains followed by re-emergence.

Morphology and Key Life Stages of Schistosoma

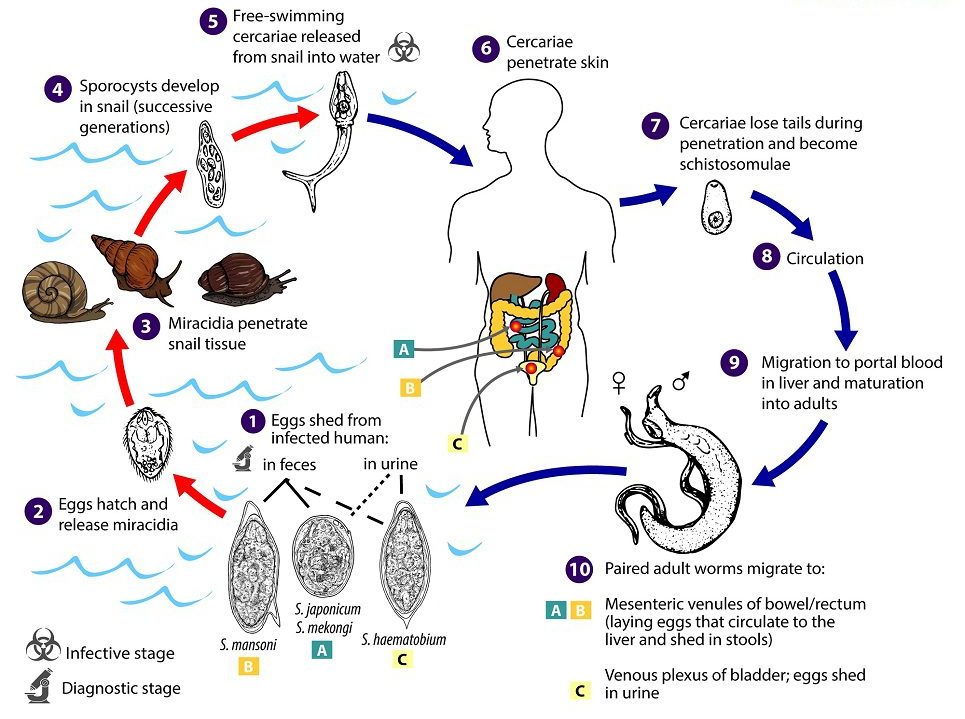

The life cycle of Schistosoma parasites is complex, involving both human and snail hosts, and each stage of development has distinct morphological features that reflect its role in survival, transmission, and disease.

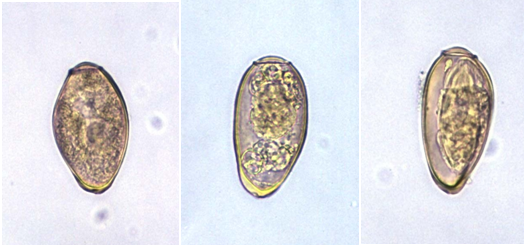

Eggs are the central drivers of pathology in schistosomiasis (Figure 1). Each species of Schistosoma produces eggs with a characteristic size and spine arrangement, which is an important diagnostic feature. Schistosoma haematobium eggs are elongated with a distinctive terminal spine, while S. mansoni eggs are also elongated but bear a prominent lateral spine. In contrast, S. japonicum eggs are more rounded and smaller, with only a subtle lateral spine. When deposited in host tissues, these eggs release antigens that stimulate intense immune responses, leading to granuloma formation and eventual fibrosis in organs such as the liver, intestine, and bladder.

From the egg hatches the miracidium, a ciliated, free-swimming larval stage adapted for seeking out and infecting a specific freshwater snail host. The miracidium is short-lived, surviving only hours in the environment, and relies on rapid, active swimming guided by light and chemical cues to locate a snail. Once it penetrates the snail, the miracidium transforms into a sporocyst.

Inside the snail, the sporocyst undergoes asexual reproduction. Germinal cells within the sporocyst proliferate to produce large numbers of daughter sporocysts, which in turn generate vast numbers of cercariae. This amplification process is critical to the parasite’s success, as a single miracidium can give rise to thousands of infectious larvae, ensuring that even infrequent snail infections can sustain transmission in a community.

The cercaria is the next free-swimming stage, recognizable by its elongated body and bifurcated, forked tail that aids in propulsion through water. Cercariae are highly motile and actively seek out human skin, to which they are attracted by body heat and surface chemicals. Upon contact, they penetrate the epidermis within minutes, shed their tails, and transform into schistosomula.

The schistosomulum is an immature worm that enters the bloodstream and migrates through the lungs to the liver. Over several weeks, it matures into an adult worm. Adults are dioecious separate male and female worms – unlike most trematodes. The thicker, shorter male encloses the slender female within a specialized groove, and together they migrate to venous plexuses of the bladder or intestines depending on the species. Adults can survive for years, continuously producing eggs that perpetuate both transmission and disease.

Signs and Symptoms of schistosomiasis

The clinical picture of schistosomiasis varies depending on the stage of infection, the intensity of exposure, and the species involved. In many cases, especially in the early phase, people may have no noticeable symptoms. However, the disease can evolve through several stages, from subtle skin changes to severe chronic complications affecting multiple organs.

- Early infection (acute phase)

Shortly after cercariae penetrate the skin, some individuals develop a localized rash or itching at the entry site, often referred to as “swimmer’s itch.” This is usually mild and transient, lasting a few days. Within one to two months, as the parasites mature and begin to produce eggs, systemic symptoms may appear. These can include fever, chills, cough, muscle and joint aches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and general malaise. In non-immune individuals, such as travelers or those experiencing their first infection, this acute stage may be pronounced and is sometimes called Katayama fever.

- Chronic infection

Most people in endemic areas experience repeated exposures and ongoing infections, which lead to chronic disease. Over time, the body’s immune response to trapped eggs causes inflammation and scarring in affected organs. In children, repeated infections are particularly damaging, leading to anemia, stunted growth, malnutrition, and reduced cognitive development, which in turn contribute to poor school performance and learning difficulties.

Organ-specific complications of schistosomiasis:

- Intestinal and hepatic disease: abdominal pain, blood in stool, hepatosplenomegaly, and portal hypertension that may lead to variceal bleeding.

- Urogenital disease: blood in urine, painful urination, bladder wall damage, kidney problems, and in women, genital lesions that may cause infertility or increase vulnerability to other infections.

- Neurological involvement: in rare cases, eggs lodge in the brain or spinal cord, resulting in seizures, paralysis, or other neurological deficits.

The progression from silent infection to severe, life-altering disease makes early detection, treatment, and prevention critical.

Life Cycle of Schistosoma

- Human excretion of eggs: Infected individuals release eggs into the environment through urine (S. haematobium) or feces (S. mansoni, S. japonicum). Once deposited in freshwater, the eggs hatch, releasing free-swimming miracidia, which seek out specific snail hosts (Figure 2).

- Snail infection and amplification: Miracidia penetrate the tissues of susceptible freshwater snails, such as Biomphalaria for S. mansoni, Bulinus for S. haematobium, and Oncomelania for S. japonicum. Within the snail, the parasite undergoes asexual reproduction, producing large numbers of cercariae. The distribution and abundance of the appropriate snail species largely determine the intensity and geographic range of transmission.

- Cercarial release and human exposure: Cercariae are released into water following circadian patterns – daytime peaks are typical for S. mansoni and S. haematobium, while S. japonicum may have nocturnal activity depending on ecological conditions. Cercarial numbers fluctuate with environmental factors such as light, temperature, and snail density, and human water-use patterns can further influence exposure risk. Cercariae are short-lived in water, sensitive to drying, and can be inactivated by water treatment.

- Skin penetration and schistosomula development: Cercariae penetrate human skin, lose their tails, and transform into schistosomula. These larvae migrate through the lymphatic system and bloodstream, passing through the lungs and eventually reaching the liver or portal circulation. There, they mature into adult worms over several weeks before migrating to their final venous locations (mesenteric or pelvic veins) to begin egg production.

- Clinical relevance of timing: The maturation period of schistosomes is clinically important because praziquantel is less effective against immature worms. Early treatment after exposure may not eliminate all parasites, necessitating repeat therapy to ensure eradication.

. Under appropriate conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia

. Under appropriate conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia  , which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts

, which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts  . The stages in the snail include two generations of sporocysts

. The stages in the snail include two generations of sporocysts  and the production of cercariae

and the production of cercariae  . Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host

. Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host  , and shed their forked tails, becoming schistosomulae

, and shed their forked tails, becoming schistosomulae  . The schistosomulae migrate via venous circulation to lungs, then to the heart, and then develop in the liver, exiting the liver via the portal vein system when mature,

. The schistosomulae migrate via venous circulation to lungs, then to the heart, and then develop in the liver, exiting the liver via the portal vein system when mature,

. Male and female adult worms copulate and reside in the mesenteric venules, the location of which varies by species (with some exceptions)

. Male and female adult worms copulate and reside in the mesenteric venules, the location of which varies by species (with some exceptions)  . For instance, S. japonicum is more frequently found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine

. For instance, S. japonicum is more frequently found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine  , and S. mansoni occurs more often in the inferior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine

, and S. mansoni occurs more often in the inferior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine  . However, both species can occupy either location and are capable of moving between sites. S. intercalatum and S. guineensis also inhabit the inferior mesenteric plexus but lower in the bowel than S. mansoni. S. haematobium most often inhabitsin the vesicular and pelvic venous plexus of the bladder

. However, both species can occupy either location and are capable of moving between sites. S. intercalatum and S. guineensis also inhabit the inferior mesenteric plexus but lower in the bowel than S. mansoni. S. haematobium most often inhabitsin the vesicular and pelvic venous plexus of the bladder  , but it can also be found in the rectal venules. The females (size ranges from 7–28 mm, depending on species) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni,S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. intercalatum/guineensis) and of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively

, but it can also be found in the rectal venules. The females (size ranges from 7–28 mm, depending on species) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni,S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. intercalatum/guineensis) and of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively  . CDC

. CDCPathogenesis of Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis pathogenesis involves a dynamic interaction between egg deposition, host immune response, granuloma formation, and chronic fibrosis, producing a spectrum of clinical consequences from acute systemic illness to severe chronic organ damage. Schistosomiasis is primarily an egg-driven disease, meaning that while adult worms live in the veins and are relatively well tolerated by the host, it is the eggs they produce that drive most of the pathology. After pairing, adult worms release eggs into the bloodstream. These eggs are transported toward the lumen of the gut in intestinal species (S. mansoni, S. japonicum) or the bladder in urogenital species (S. haematobium). However, a significant proportion of eggs fail to reach the lumen and become trapped in host tissues, including the liver, bladder, intestinal wall, genital tract, and occasionally the central nervous system.

Once lodged in tissues, the eggs secrete antigenic proteins that interact with the host immune system. These antigens strongly stimulate a Th2-polarized immune response, characterized by the production of cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-5 (IL-5), and interleukin-13 (IL-13). This response recruits immune cells, particularly eosinophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts, to the site of the eggs. The host immune system forms granulomas – which are organized clusters of immune cells that surround the eggs in an attempt to contain the antigenic material. While granuloma formation helps limit tissue damage caused directly by egg-secreted toxins, it also generates significant collateral injury. Over time, persistent inflammation leads to fibrosis, scarring of tissues, and disruption of normal organ architecture.

The pattern and severity of tissue damage vary depending on the species of Schistosoma involved and the organs affected. In intestinal species such as S. mansoni and S. japonicum, repeated egg deposition in the liver and mesenteric veins leads to periportal fibrosis, thickening of the portal tracts, and impaired blood flow through the liver. This fibrosis can progress to portal hypertension, resulting in compensatory splenomegaly and the development of varices in the esophagus or stomach, which are prone to life-threatening bleeding. In urogenital schistosomiasis caused by S. haematobium, eggs trapped in the bladder wall and ureters induce chronic inflammation and scarring. This may lead to hydronephrosis, obstructive uropathy, infertility, and an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder in long-standing infections.

Beyond organ-specific damage, the host can also experience systemic manifestations. In primary infections, especially in individuals with no prior exposure, the sudden onset of egg production can trigger Katayama syndrome, an acute systemic reaction similar to serum sickness. Patients may develop fever, malaise, myalgia, cough, and marked eosinophilia, reflecting widespread immune activation as the body responds to the newly deposited eggs. Although often self-limiting, Katayama syndrome can be severe and occasionally life-threatening in non-immune individuals.

Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) represents another critical aspect of pathogenesis. Eggs deposited in the genital tract provoke localized inflammation, resulting in mucosal lesions, bleeding, pain, and infertility. These lesions also compromise the integrity of the mucosa, which can significantly increase susceptibility to HIV infection, making FGS a major public health concern in endemic regions. Similar pathological mechanisms can occur in males, though less frequently documented.

The combination of immune-mediated tissue injury, fibrosis, and organ-specific sequelae explains why chronic schistosomiasis can lead to substantial morbidity. The pathological outcomes are not merely the result of parasite presence but rather reflect the host’s immune system attempting to contain and neutralize the antigens released by the eggs. Consequently, schistosomiasis exemplifies a disease in which the host’s defense mechanisms contribute substantially to disease severity, highlighting the complex interplay between parasite biology and host immunity.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

Diagnosing schistosomiasis requires a careful combination of exposure history, clinical findings, and appropriate laboratory tests. Because the parasite’s eggs take several weeks to mature and be excreted in stool or urine after initial infection, timing is crucial. Testing too early can yield false negatives, particularly in travelers or individuals with recent exposure. A comprehensive diagnostic approach considers both direct parasitological evidence and indirect indicators of infection or host response.

A. Parasitological Methods (Detecting Eggs Directly)

Direct identification of parasite eggs remains the cornerstone for confirming schistosomiasis, particularly in endemic areas.

- Kato-Katz Thick Smear (Stool) technique

The Kato-Katz technique involves preparing a standardized stool smear that allows both detection and quantification of eggs, expressed as eggs per gram of feces. It is widely used for S. mansoni and S. japonicum mapping, community surveys, and monitoring control programs. The method is simple, inexpensive, and provides semi-quantitative data on infection intensity. However, its sensitivity decreases in low-intensity infections, and single stool samples can miss light infections. To improve accuracy, repeated stool collections over consecutive days and multiple Kato-Katz slides per sample are recommended. This approach increases the likelihood of detecting eggs that may be shed intermittently.

- Urine Filtration or Centrifugation (Microscopy) technique

For S. haematobium, egg detection relies on urine microscopy. Collecting urine at midday, when egg excretion peaks, maximizes sensitivity. Filtration or centrifugation concentrates the eggs, enhancing visibility under a microscope. This method is particularly effective in endemic communities, but its sensitivity can be limited in light infections or in individuals with chronic disease where egg output may fluctuate.

B. Antigen Detection (Identifying Active Infection)

Antigen-based diagnostics detect circulating parasite products in blood or urine, providing evidence of active infection independent of egg excretion.

- Point-of-Care Circulating Cathodic Antigen (POC-CCA) Test

The POC-CCA urine test has gained popularity for field surveys of intestinal schistosomiasis, particularly S. mansoni. It is rapid, easy to use, and more sensitive than a single Kato-Katz in detecting low-intensity infections. However, interpretation of faint or “trace” bands can be challenging, particularly in low-prevalence settings, and confirmatory testing may sometimes be required.

- Circulating Anodic Antigen (CAA) Assays

CAA tests, usually performed in laboratory settings, detect soluble schistosome antigens in blood or urine. They are highly sensitive, even for low-intensity infections, and are particularly useful for elimination programs where standard parasitological tests may miss residual infections.

C. Serology (Detecting Host Antibody Response) technique

Serological tests identify antibodies generated against schistosome antigens. They are most useful for detecting prior exposure, especially in travelers or in non-endemic regions. While sensitive, serology has limitations: antibodies can persist long after the infection has cleared, making it impossible to distinguish active infection from past exposure. Consequently, serology is of limited use for monitoring treatment success or confirming cure.

D. Molecular Methods (PCR-Based Detection)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays can detect parasite DNA in stool, urine, blood, or genital swabs. These tests are highly sensitive and species-specific, making them invaluable in research settings, low-transmission environments, or for diagnosing female genital schistosomiasis (FGS). PCR can identify infections even when egg output is minimal, but it requires specialized laboratory infrastructure and is currently not widely used in routine field programs.

E. Imaging and Specialized Diagnostics

Imaging complements laboratory tests, particularly for assessing disease complications:

- Ultrasonography using standardized protocols allows visualization and staging of hepatosplenic disease, including periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, and splenomegaly. It is an essential tool for morbidity assessment in endemic areas.

- Cystoscopy provides direct visualization of bladder lesions in S. haematobium infections, identifying granulomas, sandy patches, and other urogenital pathology.

- Colposcopy and genital PCR are increasingly applied in the diagnosis and research of female genital schistosomiasis, enabling early detection of mucosal lesions and subclinical infections.

Treatment of Schistosomiasis

The cornerstone of schistosomiasis treatment is praziquantel (PZQ), a highly effective and widely available anti-parasitic medication. Praziquantel is a safe, effective, and essential tool in the treatment and control of schistosomiasis. Its proper use requires attention to dosing, timing relative to worm maturation, and special considerations for pregnant women and children. Praziquantel’s mechanism of action involves rapid disruption of calcium ion regulation within the adult worms, leading to spastic paralysis. This paralysis immobilizes the worms and damages their protective tegument, exposing them to the host’s immune system and facilitating their clearance. While the exact molecular targets of praziquantel remain under investigation, its clinical efficacy against adult schistosomes has been well established over decades of use.

For most clinical and public health programs, the standard dose of praziquantel is 40 mg per kilogram of body weight, administered orally as a single dose. In certain clinical contexts, this dose may be divided into two 20 mg/kg doses spaced four hours apart, or in some cases a total dose of up to 60 mg/kg is used, particularly when higher intensity infections are suspected. In mass drug administration campaigns, the single-dose 40 mg/kg regimen is the most commonly adopted approach due to its practicality and demonstrated effectiveness. In individual patients, particularly those with recent exposure or suspected immature infections, repeat dosing may be required to ensure complete eradication of worms that were initially resistant to treatment because of their immature stage.

The efficacy of praziquantel is highest against mature adult worms. Immature worms, known as schistosomula, are less susceptible, which has important implications for timing treatment. In travelers or populations with recent freshwater exposure, it is recommended to wait six to eight weeks after the last contact with potentially contaminated water before initiating treatment, allowing worms to mature and become fully vulnerable. Alternatively, treatment may be given promptly, followed by a second dose four to six weeks later to target worms that have matured in the interim. Side effects are generally mild and transient, commonly including gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, dizziness, headache, or fatigue.

Special populations require careful consideration. Pregnant women, particularly after the first trimester, can safely receive praziquantel, and its use is recommended in endemic areas to prevent morbidity in both mother and child. Pediatric formulations and weight-adjusted dosing allow safe administration to preschool and school-age children, who are often at the highest risk of infection. National and local guidelines should always be consulted for specific recommendations regarding treatment timing, dosing, and safety in vulnerable populations.

Prevention, Control, and Elimination Strategies for Schistosomiasis

Controlling schistosomiasis requires a comprehensive and integrated strategy, as drug treatment alone cannot interrupt transmission. The life cycle of Schistosoma depends on the interplay between humans, freshwater snails, and the environment, making it essential that control efforts target all components simultaneously. Effective public health programs therefore combine preventive chemotherapy, improved water and sanitation, snail control, surveillance, and health education, with interventions adapted to local epidemiology and community needs.

Progress toward elimination demands coordinated action across multiple sectors health, education, water and sanitation, and environmental management. Preventive chemotherapy provides rapid relief by reducing the parasite burden, while WASH initiatives and snail control tackle the environmental sources of infection. At the same time, surveillance systems and community engagement ensure that programs remain targeted, responsive, and sustainable.

By addressing schistosomiasis through this holistic and multi-sectoral approach, public health initiatives can not only reduce morbidity and break transmission cycles but also deliver broader benefits strengthening health systems, enhancing education outcomes, and improving the overall well-being of affected communities. The following are some notable preventive approaches:

- Preventive Chemotherapy (Mass Drug Administration)

Preventive chemotherapy, typically implemented as mass drug administration (MDA), is the cornerstone of schistosomiasis control. Praziquantel, the drug of choice, is administered periodically to populations at risk, especially school-age children, who experience the highest rates of infection and reinfection. MDA reduces individual morbidity by clearing adult worms and decreases community egg output, which in turn lowers environmental contamination and transmission risk. The frequency and coverage of MDA campaigns are determined by community prevalence: high-prevalence areas may require annual treatment, while lower-prevalence areas may need less frequent interventions. By regularly treating at-risk populations, MDA programs help reduce the overall burden of disease, prevent chronic complications, and serve as a foundation for longer-term elimination efforts.

- Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

Improving access to safe water, adequate sanitation, and hygiene practices is critical to sustaining reductions achieved through MDA. Safe water sources prevent exposure to cercariae-infested freshwater, while proper sanitation reduces contamination of water bodies with human excreta containing schistosome eggs. Hygiene education encourages behaviors such as avoiding swimming or washing in unsafe water, promoting handwashing, and using latrines. WASH interventions are particularly effective when integrated into schools, communities, and households, creating long-term environmental and behavioral changes that limit transmission. Sustainable WASH improvements not only prevent reinfection but also contribute to broader health benefits beyond schistosomiasis, including reductions in other water-borne diseases.

- Snail Control and Environmental Management

Freshwater snails serve as the intermediate hosts for Schistosoma, and controlling their populations is an essential component of reducing transmission. Programs use a combination of chemical, biological, and environmental approaches. Molluscicides, such as niclosamide, can effectively reduce snail numbers in targeted water bodies, while biological control methods including the introduction of snail predators offer environmentally sustainable options. Habitat modification, vegetation clearance, and improved water management can also limit snail breeding sites. Effective snail control must be carefully planned to minimize ecological disruption and consider the social and economic needs of communities that rely on water bodies for agriculture, fishing, or daily activities.

- Surveillance and Focal Responses

As control programs reduce prevalence, transmission becomes more heterogeneous, often concentrated in specific communities or ecological niches. Surveillance using sensitive diagnostic tools, such as circulating antigen detection or molecular techniques (PCR), becomes increasingly important to identify remaining infections. Focal responses including targeted treatment campaigns, localized snail control, and catch-up MDA – allow resources to be concentrated where they are most needed. Integrating schistosomiasis surveillance with other neglected tropical disease programs enhances efficiency, ensures timely response, and supports progress toward elimination.

- Health Education and Community Engagement

Community engagement and health education complement technical interventions by promoting awareness of schistosomiasis, encouraging protective behaviors, and ensuring local support for control measures. School-based programs can teach children about safe water contact and personal hygiene, while broader community initiatives can engage adults, farmers, and caregivers. Linking schistosomiasis control to reproductive health and HIV programs, particularly for female genital schistosomiasis, enhances impact by addressing overlapping health risks. Empowering communities to take ownership of prevention measures strengthens adherence to MDA, WASH, and snail control interventions, making elimination efforts more sustainable.

Source

WHO – Schistosomiasis fact sheets and technical guidance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis

CDC – Clinical overview, diagnosis & treatment guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/schistosomiasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Platt II, R. N., Enabulele, E. E., Adeyemi, E., Agbugui, M. O., Ajakaye, O. G., Amaechi, E. C., Ejikeugwu, C. P.,Igbeneghu, C., Njom, V. S., Dlamini, P., Arya, G. A., Diaz, R., Rabone, M., Allan, F., Webster, B., Emery, A., Rollinson, D., & Anderson, T. J. C. (2025). Genomic data reveal a north-south split and introgression history of blood fluke populations across Africa. Nature Communications, 16, 3508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58543-6

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.