Microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi, are fundamental to the sustainability and advancement of modern agriculture and food production systems. These microscopic organisms are involved in diverse biological processes that not only support food production but also enhance the health of consumers. In an era where food insecurity continues to challenge communities in various regions of the world, the role of microbes in food production has become increasingly significant. Through biotechnological and natural processes, microbes contribute to increased crop yields, soil fertility, and enhanced growth of crop plants. Furthermore, microbial actions are central to the fermentation of food and beverages, transforming raw ingredients into safe, nutritious, and shelf-stable products with improved flavors, textures, and health benefits.

One of the most impactful contributions of microbes in agriculture is their ability to enhance soil health and plant growth. Rhizobium species, for instance, are nitrogen-fixing bacteria that form symbiotic relationships with legumes. They colonize the root nodules of these plants and convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, a form of nitrogen that plants can assimilate for growth. This natural fertilization process reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers, thus contributing to sustainable agricultural practices. Similarly, mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic associations with plant roots, extending the root system through their hyphal networks. These fungi improve water and nutrient absorption, particularly phosphorus, and can enhance plant resistance to pathogens and environmental stressors. Together, Rhizobium and mycorrhizae exemplify how microbial interactions can revolutionize food sustainability by boosting agricultural productivity naturally and sustainably.

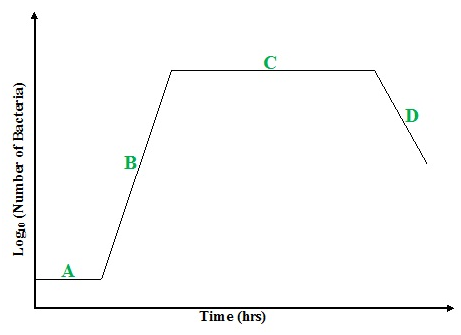

Beyond the soil, microbes have a pivotal role in the transformation of raw food ingredients through fermentation. Fermented foods have been part of human diets for thousands of years, and their production hinges on the metabolic activities of diverse microorganisms such as lactic acid bacteria (LAB), yeasts, and molds. These organisms break down carbohydrates and proteins into simpler compounds, producing organic acids, alcohols, and gases that influence the texture, flavor, nutritional profile, and shelf-life of foods.

Lactic acid bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus species, are widely used in the dairy industry to produce yogurt, cheese, kefir, sour cream, and cultured buttermilk. For example, acidophilus milk contains Lactobacillus acidophilus, a probiotic bacterium known for its ability to colonize the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and alter its microbial flora. This alteration can help mitigate the risk of gastrointestinal disorders and has been associated with reducing the incidence of colon cancer. Probiotics like L. acidophilus play a crucial role in restoring gut microbiota balance, especially following antibiotic treatments, and have been shown to stimulate immune responses.

Fermentation processes can be classified based on the temperature at which they occur. Thermophilic fermentations, carried out by thermophilic bacteria at elevated temperatures (around 45°C), are employed in the production of fermented foods such as yogurt. These high-temperature processes not only aid in developing characteristic textures and flavors but also ensure the inhibition of undesirable microbes, thus enhancing food safety. On the other hand, mesophilic fermentations occur at moderate temperatures (below 45°C) and are used in the production of cultured dairy products such as buttermilk and sour cream. Mesophilic bacteria produce organic acids that denature milk proteins, leading to the coagulation and thickening necessary for these products.

Microbial fermentation is also indispensable in the production of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. Yeasts, particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, play a central role in the alcoholic fermentation of sugars derived from grains and fruits into ethanol and carbon dioxide. This biochemical process is foundational to the production of beer, wine, and champagne. In bread-making, aerobic fermentation by yeasts produces carbon dioxide with minimal alcohol output, causing dough to rise and giving bread its soft, porous texture. The action of yeasts and bacteria in food fermentation not only preserves food but also enhances its organoleptic properties, making it more appealing to consumers.

In addition to enhancing taste and texture, fermented food products offer significant health benefits. Fermented milk products containing Bifidobacterium species have been shown to improve lactose tolerance in lactose-intolerant individuals. These products possess anticancer properties, reduce serum cholesterol levels, assist in calcium absorption, and support the synthesis of B-complex vitamins. The health-promoting properties of these microbes have been widely acknowledged, prompting the inclusion of probiotic and prebiotic foods in therapeutic diets. Patients suffering from metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal disturbances, or compromised immunity are often advised to consume fermented milk products for their beneficial effects.

Probiotics are among the most well-known microbial dietary supplements. Defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host, probiotics are increasingly used in both clinical and everyday settings. Probiotics can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, enhance the integrity of the intestinal barrier, modulate the immune system, and even impact mental health through the gut-brain axis. The administration of probiotic-rich foods and supplements is a growing area in preventive healthcare and functional nutrition.

Microbes also play essential roles in the production of non-dairy fermented foods. Soy-based products such as miso, tempeh, and soy sauce rely on molds like Aspergillus oryzae and bacteria like Bacillus subtilis for fermentation. These foods are not only rich in protein and amino acids but also offer health-promoting properties, including antioxidant activity and improved digestive health. Similarly, traditional African fermented foods such as ogi, fufu, and iru involve the participation of native microbial consortia, demonstrating the widespread cultural and geographical integration of microbial fermentation in global diets.

In beverage production, microbial fermentation is crucial for generating a wide variety of products with varying alcohol content, flavors, and nutritional values. Kombucha, a fermented tea beverage, is produced by a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeasts (SCOBY). This drink is rich in organic acids, probiotics, and antioxidants, and has gained popularity for its purported health benefits, including detoxification, improved digestion, and enhanced energy. In beer brewing, Saccharomyces pastorianus is commonly used for lager production, whereas S. cerevisiae is used for ales. Each strain imparts unique flavor profiles and contributes to the complexity of the beverage.

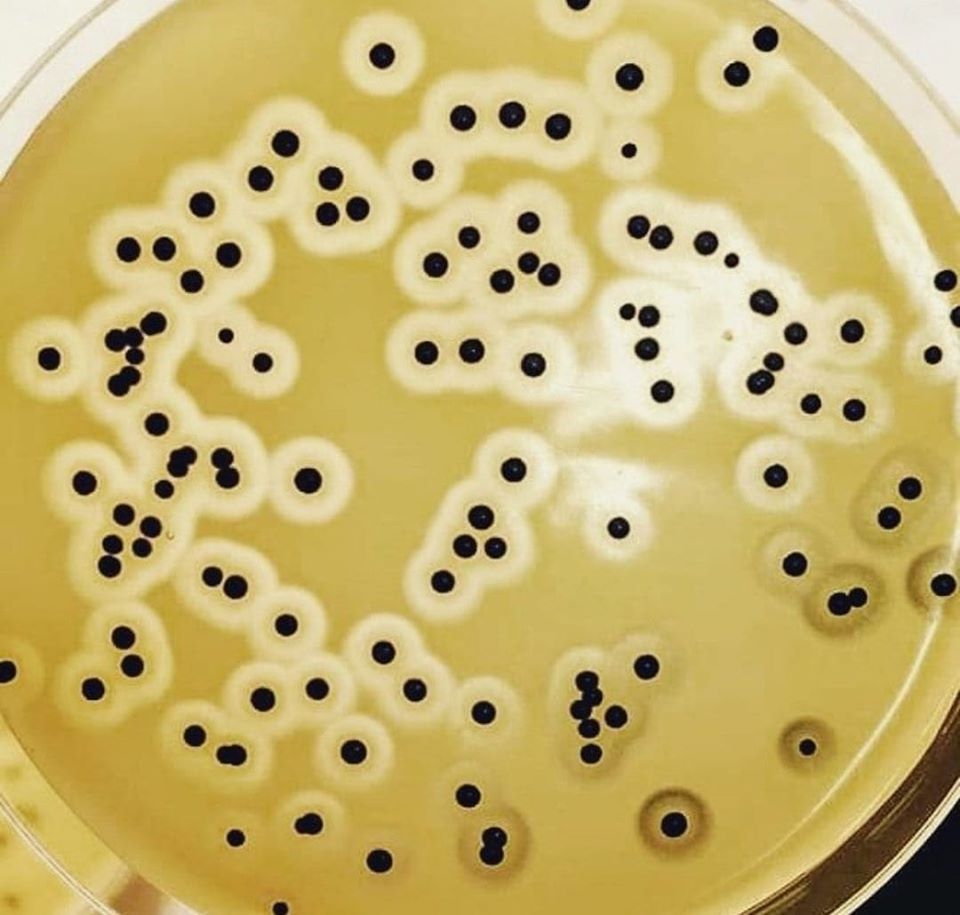

Furthermore, food safety and shelf-life can be significantly improved through microbial action. During fermentation, beneficial microbes outcompete spoilage and pathogenic organisms by producing antimicrobial compounds such as bacteriocins, organic acids, and hydrogen peroxide. This microbial antagonism ensures the microbial stability of fermented foods, reducing the need for chemical preservatives. LAB, in particular, have been widely studied for their bacteriocin-producing capabilities and are employed in food biopreservation strategies.

Enzymes produced by microbes also have important industrial applications in food processing. Amylases, proteases, and lipases from microbial sources are used to hydrolyze starches, proteins, and fats, respectively. These enzymatic reactions are employed in baking, brewing, dairy processing, and the production of sweeteners. For example, microbial proteases are used in cheese manufacturing to facilitate milk coagulation and flavor development.

In the context of biotechnology, advances in microbial genomics and metabolic engineering have opened new frontiers in food production. Genetically modified microorganisms (GMMs) can be engineered to enhance specific traits such as increased enzyme production, improved probiotic efficacy, or the biosynthesis of novel bioactive compounds. These GMMs have potential applications in producing fortified foods, reducing allergens, and developing sustainable protein alternatives. For instance, microbial fermentation is now used to produce animal-free dairy proteins like casein and whey, which are used in the development of vegan cheeses and yogurts.

Microbes are also being explored for their potential to convert agricultural and food waste into valuable products. Through fermentation, food by-products such as fruit peels, whey, and spent grains can be transformed into biofuels, organic acids, and single-cell proteins. This approach not only mitigates waste but also supports a circular economy and enhances the sustainability of food systems.

Additional Applications of Microbes in Food Production

Microorganisms continue to revolutionize various aspects of food production beyond traditional roles in fermentation and soil health. With advancements in microbiology, biotechnology, and food science, the innovative applications of microbes now extend into several cutting-edge domains. These applications not only enhance food safety, nutrition, and flavor but also promote sustainability, resource efficiency, and consumer health. Below are some key and emerging roles that microbes play in modern food systems:

- Biocontrol Agents: Certain beneficial microbes, such as Bacillus subtilis, Trichoderma harzianum, and Pseudomonas fluorescens, act as natural biocontrol agents. They suppress plant pathogens by competing for nutrients, producing antimicrobial compounds, or inducing systemic resistance in crops. The use of these microbes reduces reliance on chemical pesticides, lowering environmental pollution and pesticide residues in food. This practice supports organic and sustainable farming systems and enhances the ecological resilience of agroecosystems.

- Flavor Enhancement: Specific microbial strains are integral to developing characteristic and culturally significant flavors in fermented foods. For instance, molds like Penicillium roqueforti and Penicillium camemberti are used in the maturation of blue and soft-ripened cheeses, respectively, imparting distinctive flavors and textures. Similarly, Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc species contribute to the development of tangy and savory notes in sausages and pickled vegetables. In soy sauce production, Aspergillus oryzae breaks down soy proteins and starches into amino acids and sugars, producing rich umami flavors.

- Nutrient Fortification: Microbes can be harnessed to synthesize essential vitamins and micronutrients. For example, Propionibacterium freudenreichii is used to produce vitamin B12 in fortified dairy and plant-based products. Similarly, genetically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains have been developed to enhance folate and vitamin D content in bread and other baked goods. This microbial fortification is particularly beneficial in addressing micronutrient deficiencies in vulnerable populations, especially in regions facing malnutrition.

- Packaging Innovations: The environmental burden of plastic waste has spurred interest in biodegradable packaging materials, many of which are microbially derived. Microorganisms such as Ralstonia eutropha and Cupriavidus necator can produce biopolymers like polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are biodegradable and suitable for food packaging applications. These bioplastics offer a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to petroleum-based plastics while maintaining necessary food safety and barrier properties.

- Prebiotics Production: Prebiotics are non-digestible food components that selectively promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria. Certain microbes can produce prebiotic compounds like fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and galactooligosaccharides (GOS) during fermentation. These prebiotics support gut health by enhancing populations of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, improving digestion, nutrient absorption, and immunity. Incorporating microbially-derived prebiotics into foods contributes to functional nutrition and preventative healthcare.

- Biotransformation: Microbial biotransformation involves the conversion of food substrates into more valuable or bioactive compounds. For example, Lactobacillus species can convert lactose into lactulose, a prebiotic with mild laxative properties that supports gut health. Other transformations include the production of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a neurotransmitter with calming effects, from glutamate by certain Lactococcus strains. These conversions enhance the nutritional and therapeutic potential of foods.

- Meat Alternatives: The rise in plant-based diets and sustainability concerns has increased interest in microbial proteins. Mycoproteins, derived from filamentous fungi such as Fusarium venenatum, are cultivated in fermentation tanks to produce protein-rich meat analogs. These products mimic the texture and nutritional content of meat while offering lower environmental footprints. Commercialized under brand names like Quorn™, mycoproteins are rich in dietary fiber, essential amino acids, and have a low fat content.

- Dairy Alternatives: Microbes are also instrumental in producing dairy-like products from plant-based substrates. By fermenting almond, soy, oat, or coconut milk with cultures such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus, producers can create yogurt alternatives with similar taste and texture profiles. Innovations in microbial fermentation also facilitate the production of plant-based cheeses with complex flavor development, often incorporating molds and bacteria for ripening and aroma enhancement.

- Allergen Reduction: Microbial fermentation can be used to degrade or modify allergenic proteins in foods, thereby reducing their allergenicity. For instance, fermentation of wheat can reduce gluten content, and similar approaches have been applied to peanuts and soy. This process holds promise for developing hypoallergenic food products, making previously problematic foods more accessible to sensitive individuals.

- Biosensors for Food Safety: Microbes and microbial components are being integrated into biosensor systems to detect pathogens, toxins, and spoilage indicators in real-time. Engineered bacterial strains can respond to contaminants by producing measurable signals such as fluorescence or color change. These biosensors enhance quality control, improve traceability in the food supply chain, and reduce foodborne illness risks.

The integration of microbial technology into food systems must, however, be guided by rigorous quality control, safety assessments, and regulatory oversight. While the health benefits of microbial fermentation are well-established, the possibility of contamination or the presence of pathogenic strains in poorly managed fermentations cannot be ignored. Ensuring strain-specific identification, genomic stability, and absence of transferable antibiotic resistance genes is critical in commercial probiotic and fermentation applications.

The potentials of microbes in food production are vast and multifaceted. From enhancing crop yields and soil health to fermenting nutritious and functional foods, microbes are indispensable allies in achieving global food security and public health. Their roles in improving food taste, safety, shelf-life, and nutritional value underscore their importance in traditional and modern food systems alike. As science continues to unravel the complexities of microbial ecosystems, the application of beneficial microbes in agriculture and food production will only expand, offering innovative solutions to some of the most pressing challenges of our time. Embracing microbial biotechnology, supported by sound scientific principles and responsible practices, promises to transform food systems for a healthier and more sustainable future.

Potential Microbes Used in Food Production

Microorganisms are indispensable in food production, contributing to fermentation, preservation, texture development, flavor enhancement, nutrient fortification, and functional food innovation. Below is a list of 20 key microbes widely used in the food industry, along with their applications and examples of food they are used in producing:

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

A lactic acid bacterium used in yogurt and fermented dairy. It helps convert lactose to lactic acid, contributing to tart flavor and extended shelf life.

Example: Yogurt, acidophilus milk.

- Lactobacillus plantarum

Known for its versatility, this bacterium is used in vegetable fermentations and functional foods due to its probiotic benefits.

Example: Sauerkraut, kimchi.

- Streptococcus thermophilus

Commonly used with Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in yogurt production. It helps initiate milk fermentation and improves texture.

Example: Yogurt.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae

A yeast crucial in baking, brewing, and winemaking. It ferments sugars to produce ethanol and carbon dioxide.

Example: Bread, beer, wine.

- Penicillium camemberti

A mold used in the ripening of soft cheeses. It creates a white rind and softens cheese texture.

Example: Camembert, Brie.

- Penicillium roqueforti

This mold produces blue veins and strong flavor in blue cheeses by growing inside the cheese matrix.

Example: Roquefort, Stilton.

- Aspergillus oryzae

A filamentous fungus used to saccharify starches in soybeans and rice, facilitating fermentation.

Example: Soy sauce, miso, sake.

- Bifidobacterium bifidum

A probiotic bacterium that improves gut health. It is often added to dairy products to enhance their functional properties.

Example: Probiotic yogurt.

- Lactococcus lactis

Used in the production of buttermilk and cheese. It helps in acidification and flavor compound production.

Example: Cheddar cheese, sour cream.

- Leuconostoc mesenteroides

Initiates heterolactic fermentation and contributes to aroma and texture in vegetable fermentations.

Example: Sauerkraut, kimchi.

- Propionibacterium freudenreichii

Involved in Swiss cheese production; it creates the characteristic holes (eyes) and nutty flavor through carbon dioxide release.

Example: Emmental cheese.

- Rhizopus oligosporus

Used in the fermentation of soybeans to make tempeh. It binds soybeans into a cake and enhances nutritional quality.

Example: Tempeh.

- Bacillus subtilis

Ferments protein-rich foods like soybeans in alkaline conditions, used in traditional Asian foods.

Example: Natto (fermented soybeans).

- Zygosaccharomyces rouxii

A salt-tolerant yeast that adds aroma and umami during fermentation.

Example: Soy sauce, miso.

- Candida milleri (also known as Candida humilis)

Works symbiotically with lactic acid bacteria in sourdough fermentation to improve bread flavor and leavening.

Example: Sourdough bread.

- Fusarium venenatum

A filamentous fungus used to produce mycoprotein, a sustainable, protein-rich meat alternative.

Example: Quorn™ products.

- Geotrichum candidum

Contributes to cheese rind development and enzymatic breakdown of fats and proteins.

Example: Soft cheeses like Saint-Nectaire.

- Oenococcus oeni

Used in winemaking to perform malolactic fermentation, converting malic acid to lactic acid, which softens wine flavor.

Example: Red wine, some white wines.

- Acetobacter aceti

Oxidizes ethanol to acetic acid in aerobic conditions, essential in vinegar production.

Example: Apple cider vinegar, balsamic vinegar.

- Kluyveromyces marxianus

A thermotolerant yeast used in the dairy industry for lactose fermentation, flavor development, and probiotic functions.

Example: Fermented dairy products like kefir.

These microbes are not exhaustive of the plethora of microbes used in the food producing company to produce a wide variety of foods but they highlight the diversity and importance of microorganisms in modern food production. They play vital roles in improving food taste, shelf life, nutritional value, safety, and sustainability. Innovations in microbial biotechnology continue to expand their applications, making them integral to food system transformation, especially in the face of climate change, population growth, and health challenges.

References

Bushell M.E (1998). Application of the principles of industrial microbiology to biotechnology (ed. Wiseman, A.) Chapman and Hall, New York.

Byong H. Lee (2015). Fundamentals of Food Biotechnology. Second edition. Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey, United States.

Clark D.P and Pazdernik N (2010). Biotechnology. First edition. Elsevier Science and Technology Books, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Farida A.A (2012). Dairy Microbiology. First edition. Random Publications. New Delhi, India.

Frazier W.C, Westhoff D.C and Vanitha N.M (2014). Food Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Education (India) Private Limited, New Delhi, India.

Guidebook for the preparation of HACCP plans (1999). Washington, DC, United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service. Accessed on 20th February, 2015 from: http://www.fsis.usda.gov

Hayes P.R, Forsythe S.J (1999). Food Hygiene, Microbiology and HACCP. 3rd edition. Elsevier Science, London.

Hussaini Anthony Makun (2013). Mycotoxin and food safety in developing countries. InTech Publishers, Rijeka, Croatia. Pp. 77-100.

Jay J.M (2005). Modern Food Microbiology. Fourth edition. Chapman and Hall Inc, New York, USA.

Lightfoot N.F and Maier E.A (1998). Microbiological Analysis of Food and Water. Guidelines for Quality Assurance. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Roberts D and Greenwood M (2003). Practical Food Microbiology. Third edition. Blackwell publishing Inc, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.