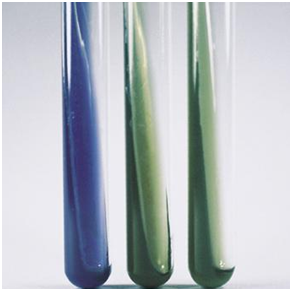

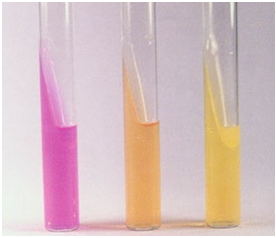

Oxidase test is used to identify microorganisms that produce the enzyme, cytochrome-c oxidase. Cytochrome-c oxidase, a respiratory enzyme is an important enzyme of the electron transport chain (ETC), where it catalyzes the transport of electrons from a donor compound (e.g. NADH) to oxygen, the final electron acceptor. If cytochrome-c oxidase is present, it will oxidize TMPPEH (the redox dye), turning it into a blue-purple colour.

The redox dye is usually clear in its reduced form. Oxidase test is used to differentiate oxidase producing bacteria (e.g. Pseudomonas) from non-oxidase producing ones (e.g. Enterobacteriaceae). Oxidase test which is very useful in differentiating between Pseudomonas and Gram negative rods is carried out using a redox reagent/dye called tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine hydrochloride (TMPPEH) which acts as the electron donor. TMPPEH (oxidase reagent) is usually stored in dark (amber) bottles kept in the refrigerator and away from light in order to avoid auto-oxidation which may reduce its potency.

The addition of 0.1 % ascorbic acid to oxidase reagent can also help to protect it against auto-oxidation. Pseudomonas, Vibrio, Pasteurella, and Brucella species are oxidase positive because they produce oxidase enzyme. This test can also be performed using an oxidase reagent strip.

PROCEDURE FOR OXIDASE TEST

- Perform this test with a pure culture of the test organism.

- Place a piece of filter paper on a clean glass slide or Petri dish.

- Add about 2 drops of oxidase reagent onto the filter paper.

- Pick a speck or colony of the test bacterium using a glass rod or the edge of a clean glass slide. Note: An oxidized or flamed inoculating loop must not be used to pick the test bacterium from the culture plate.

- Smear the inoculum of the bacterium onto the filter paper on the Petri dish plate.

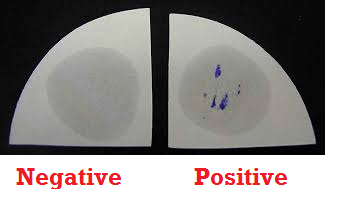

- Observe the filter paper for the presence of a blue-purple colour which starts to develop within 5-10 seconds. This is indicative of a positive oxidase test (Figure 1). Absence of a blue-purple colour indicates a negative test result.

References

Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. World Health Organization (WHO), 1991. Available from WHO publications, 1211 Geneva, 27-Switzerland.

Beers M.H., Porter R.S., Jones T.V., Kaplan J.L and Berkwits M (2006). The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Eighteenth edition. Merck & Co., Inc, USA.

Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th edition. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Institute of Health. HHS Publication No. (CDC) 21-1112.2009.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part I. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Cheesbrough M (2010). District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. Part 2. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Collins C.H, Lyne P.M, Grange J.M and Falkinham J.O (2004). Collins and Lyne’s Microbiological Methods. Eight edition. Arnold publishers, New York, USA.

Disinfection and Sterilization. (1993). Laboratory Biosafety Manual (2nd ed., pp. 60-70). Geneva: WHO.

Garcia L.S (2010). Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Garcia L.S (2014). Clinical Laboratory Management. First edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Fleming, D. O., Richardson, J. H., Tulis, J. I. and Vesley, D. (eds) (1995). Laboratory Safety: Principles and practice. Washington DC: ASM press.

Dubey, R. C. and Maheshwari, D. K. (2004). Practical Microbiology. S.Chand and Company LTD, New Delhi, India.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.