Microbial growth is a fundamental biological process that governs the proliferation of microbial cells in response to environmental conditions and nutrient availability. Understanding the various growth phases and cultivation systems used in microbiology is essential for disciplines such as microbial physiology, environmental microbiology, industrial biotechnology, and clinical diagnostics. Growth patterns of microbial populations typically follow predictable stages that reflect changes in cellular activity and environmental conditions.

Growth Patterns in Batch and Continuous Cultures

Microorganisms respond dynamically to their environmental conditions, especially in relation to nutrient availability. In laboratory and industrial settings, microbial growth is commonly studied using two principal cultivation systems: batch culture and continuous culture. Each system offers distinct insights into microbial behavior, and their application depends on the research goals or industrial requirements.

Batch Culture: A Closed System of Microbial Growth

A batch culture represents a closed microbial cultivation system in which a fixed volume of growth medium is inoculated with microbial cells, and no further addition of nutrients or removal of waste occurs during the growth period. The environment within a batch culture changes progressively as nutrients are consumed and metabolic byproducts accumulate. These fluctuations significantly influence the microbial growth phases.

Test tubes, flasks, and Petri dishes used for cultivating microorganisms in laboratories are common examples of batch culture systems. Batch cultures typically go through a complete microbial growth cycle, characterized by four distinct growth phases: lag, log (exponential), stationary, and death phases. Since no fresh nutrients are added and waste is not removed, batch systems inherently limit the duration and extent of exponential growth. Eventually, the depletion of essential nutrients and accumulation of toxic metabolites lead to growth cessation and microbial death.

Despite its limitations, the batch culture system is particularly useful in studying microbial life cycle dynamics and the production of secondary metabolites such as antibiotics. It is also applicable in fermentation processes that require controlled nutrient limitation or temporal regulation.

Continuous Culture: An Open System for Sustained Growth

In contrast, a continuous culture system is an open growth environment where nutrients are continually supplied, and waste products and excess cells are constantly removed. This system enables microbial populations to be maintained in a steady-state exponential growth phase over an extended period. Continuous cultures are ideal for studying microbial metabolism under stable conditions, assessing growth kinetics, and optimizing biomass production.

The hallmark of continuous culture is the ability to maintain optimal environmental conditions for microbial proliferation through precise regulation of growth parameters such as nutrient concentration, pH, temperature, oxygen levels, and dilution rate. Continuous culture systems are invaluable in industrial microbiology and bioprocess engineering for producing large quantities of microbial biomass or metabolites.

There are two primary types of continuous culture systems:

1. Chemostat

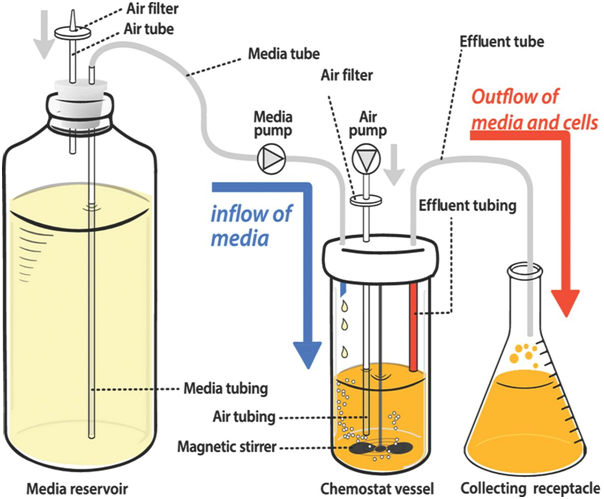

A chemostat is the most widely used continuous culture system (Figure 1). In this bioreactor, fresh sterile growth medium is continuously added at a constant rate, while an equal volume of culture liquid—containing cells and metabolic waste—is simultaneously removed. This design maintains a constant culture volume and allows the system to reach and sustain a steady-state condition, where the growth rate of microorganisms is limited by a specific nutrient known as the limiting nutrient.

The dilution rate (D), defined as the flow rate of fresh medium divided by the culture volume, is a crucial parameter in chemostat operation. By adjusting the dilution rate, scientists can control the specific growth rate (μ) of the microbial population. When the dilution rate exceeds the maximum specific growth rate of the microorganism, washout occurs, and the microbial population declines.

Chemostats are designed with fittings for influent and effluent flow, aeration ports, mixing devices, and sensors for real-time monitoring of growth parameters. They enable researchers to:

- Investigate microbial kinetics and physiology under defined nutrient limitations.

- Analyze metabolic pathways and gene expression.

- Study adaptive evolution by applying controlled selective pressures.

- Optimize production of primary and secondary metabolites.

2. Turbidostat

A turbidostat is another form of continuous culture system that differs from a chemostat primarily in its operational control mechanism. Instead of relying on nutrient limitation to regulate microbial growth, a turbidostat uses optical density (OD) or turbidity measurements to maintain cell density within a defined range. As soon as turbidity exceeds a set threshold—indicating increased microbial biomass—fresh medium is introduced, and excess culture is removed.

Turbidostats are especially useful for cultivating microorganisms at their maximum growth rate, as they operate without a limiting nutrient. They are ideal for investigating microbial behavior under non-limiting nutrient conditions and for studies involving fast-growing or highly sensitive microbial species. Compared to chemostats, turbidostats typically function at higher dilution rates, which allow for more rapid response to changes in microbial density.

Phases of Microbial Growth in Batch Culture

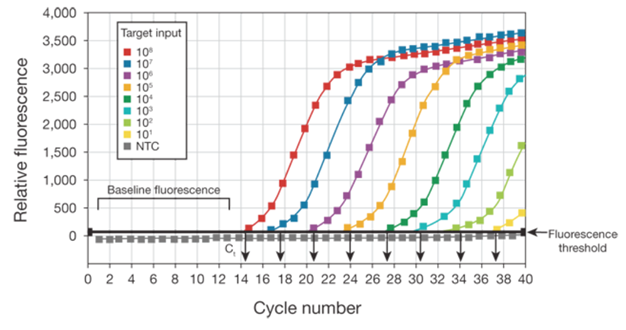

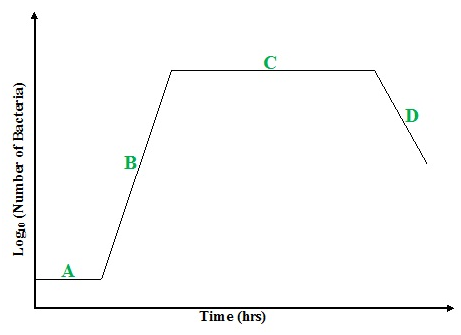

Microbial growth in batch culture follows a distinctive sigmoidal (S-shaped) curve that reflects changes in population dynamics and physiological states (Figure 2). This growth pattern is typically divided into four key phases: lag phase, log (exponential) phase, stationary phase, and death (decline) phase. Each phase corresponds to specific biological processes and is influenced by multiple factors, such as nutrient composition, oxygen availability, temperature, pH, osmotic conditions, and the intrinsic adaptability of the microorganism.

1. Lag Phase: Acclimatization and Biosynthesis

The lag phase is the initial period after microorganisms are introduced into a fresh culture medium. During this stage, cells are metabolically active but not yet dividing. This apparent inactivity conceals an intense period of internal reorganization and preparation for growth.

Key activities during the lag phase include:

- Enzyme synthesis: Cells begin synthesizing new enzymes to exploit the available nutrients in the fresh medium. For example, Escherichia coli grown in a medium with lactose after being cultured in glucose must first synthesize β-galactosidase to utilize lactose.

- Macromolecular repair: Damaged DNA, RNA, or proteins from previous stress conditions or long-term storage are repaired.

- Membrane and protein adaptation: Cells alter their membrane composition and protein expression to match the osmolarity, temperature, and pH of the new environment.

- Induction of metabolic pathways: Metabolic switching is crucial when moving from nutrient-rich media to minimal media. For example, Pseudomonas putida transferred to a medium containing aromatic compounds as a sole carbon source activates genes for xenobiotic degradation.

Examples:

- Bacillus subtilis spores germinating into vegetative cells undergo an extended lag phase due to the need for spore coat degradation and rehydration.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) requires time to upregulate genes involved in ethanol metabolism when shifted from glucose to ethanol as a carbon source.

The duration of the lag phase can vary from minutes to several hours depending on:

- The physiological state of the inoculum (young vs. old culture).

- The degree of similarity between the old and new media.

- The temperature shift between the storage and growth environments.

Although no cell division occurs, the lag phase is essential for ensuring cells are fully prepared for sustained growth.

Keys:

A = Lag phase

B = Log (exponential Phase)

C = Stationary phase

D = Decline & Death Phase

2. Log (Exponential) Phase: Rapid Cell Division and Metabolic Efficiency

During the log phase, cells begin to divide at a constant and rapid rate, resulting in an exponential increase in population. Microorganisms are in their most active state metabolically, making this phase ideal for studies in microbiology, biochemistry, and industrial fermentation.

Key features of the log phase include:

- Balanced growth: All cellular components (DNA, RNA, proteins, membranes) are synthesized proportionately.

- High metabolic activity: Pathways for energy production (like glycolysis, TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation) are fully active.

- Uniformity: Cells exhibit homogeneity in size, composition, and physiological behavior, allowing for reproducible experimental data.

- Optimal product formation: Many primary metabolites are synthesized in this phase, including:

- Ethanol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- Citric acid by Aspergillus niger

- Enzymes such as amylases, proteases, and cellulases by bacterial and fungal strains

Examples:

- In industrial biotechnology, Corynebacterium glutamicum is grown in batch cultures to produce L-glutamate or L-lysine during exponential growth.

- In clinical microbiology, antibiotics are most effective against pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus during their log phase, when cell wall synthesis is active.

Due to the high growth rate and metabolic activity, this phase is used to calculate key parameters like specific growth rate, generation time, and biomass yield.

3. Stationary Phase: Nutrient Limitation and Stress Adaptation

As nutrients become scarce and toxic metabolites accumulate, cell division slows down and eventually stops, marking the onset of the stationary phase. During this phase, the rate of cell division equals the rate of cell death, resulting in a relatively stable population size.

Biological processes during this phase include:

- Nutrient limitation: Depletion of essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, or carbon halts DNA replication and protein synthesis.

- Waste accumulation: Toxic products like organic acids (e.g., lactic acid from Lactobacillus) inhibit further growth.

- Stress responses: Microbes activate global stress regulators such as the RpoS sigma factor in E. coli, which enhances resistance to oxidative stress, osmotic pressure, and acidic environments.

- Secondary metabolite production: Many bioactive compounds are synthesized in this phase, including:

- Antibiotics like penicillin (Penicillium chrysogenum) and streptomycin (Streptomyces griseus)

- Pigments such as prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens

- Siderophores for iron scavenging under nutrient limitation

Examples:

- In winemaking, S. cerevisiae enters the stationary phase as sugar levels drop, shifting metabolism to preserve survival and stress resistance.

- In pharmaceutical fermentation, producers often harvest antibiotics during this phase to maximize yield.

Although the cell number remains static, cells undergo profound physiological changes, including reduced cell size, thickening of cell walls, and accumulation of storage compounds like polyhydroxybutyrates (PHBs).

4. Death (Decline) Phase: Cellular Decline and Survival Strategies

If unfavorable conditions persist—continued nutrient depletion, increasing toxicity, or pH changes—the culture enters the death phase. In this phase, cell death exceeds cell replication, leading to a net decrease in viable population.

Processes associated with the death phase include:

- Cell lysis: Breakdown of membranes and release of cellular contents due to autolytic enzymes or osmotic shock.

- DNA damage: Oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species can fragment DNA.

- Loss of viability: Cells lose the ability to form colonies on nutrient media.

Survival mechanisms and adaptations:

- Endospore formation: Bacteria like Clostridium botulinum and Bacillus anthracis form dormant spores resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals.

- Persister cells: A small fraction of microbial cells enter a dormant, antibiotic-tolerant state, especially in pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- Viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state: Cells remain alive but undetectable by standard culturing methods, posing challenges in food safety and clinical diagnostics.

Examples:

- In nutrient-depleted aquatic environments, Vibrio cholerae may enter a VBNC state, evading detection but remaining infectious.

- In chronic infections like biofilm-associated endocarditis, Staphylococcus epidermidis persists despite antimicrobial treatment due to persister cells.

Understanding the death phase has important implications for:

- Sterilization protocols

- Food spoilage prediction

- Antibiotic resistance studies

- Long-term microbial ecology

The four phases of microbial growth in batch culture—lag, log, stationary, and death—offer a dynamic view of how microorganisms respond to their environment over time. Each phase is marked by unique physiological states, metabolic priorities, and survival strategies. These phases not only provide fundamental insights into microbial life cycles but also have practical applications in medicine, biotechnology, environmental microbiology, and industrial fermentation. Understanding these growth dynamics allows researchers and industry professionals to design more efficient cultivation systems, optimize product yields, and control microbial activity in diverse settings.

Applications and Implications of Microbial Growth Phases

Understanding the distinct phases of microbial growth—lag, exponential (log), stationary, and death—is crucial across multiple disciplines. Each phase offers unique physiological and biochemical characteristics that can be leveraged or mitigated depending on the goal, whether it’s enhancing metabolite production, controlling infection, or studying ecological interactions. The insights drawn from microbial growth dynamics guide strategies in research, industry, medicine, and environmental management.

1. Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology

Microbial growth phases are central to the design and optimization of industrial fermentation processes. The physiological state of microbes determines not only their growth rate but also their metabolic outputs, which can be either primary or secondary metabolites.

- Primary Metabolite Production (Log Phase): During the exponential phase, microorganisms exhibit high metabolic activity and produce compounds essential for their growth, such as ethanol, lactic acid, amino acids, and enzymes. For instance:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae is used to produce bioethanol in fuel industries during the log phase.

- Aspergillus niger generates citric acid, a key food additive, primarily during exponential growth.

- Secondary Metabolite Production (Stationary Phase): As cells enter nutrient-limited conditions in the stationary phase, many begin producing secondary metabolites like antibiotics, pigments, and toxins. These have significant economic and pharmaceutical value:

- Streptomyces spp. produce streptomycin and other antibiotics during the stationary phase.

- Penicillium chrysogenum yields penicillin, whose production peaks as growth slows.

Additionally, understanding growth kinetics aids in:

- Scale-up operations, ensuring that optimal conditions in small fermenters translate to industrial bioreactors.

- Probiotic production, where maintaining viability and metabolic vigor is crucial.

- Single-cell protein (SCP) cultivation, using microbes like Chlorella or Spirulina to create protein-rich biomass for human and animal consumption.

2. Environmental Microbiology

Microbial growth phases are vital for understanding how microorganisms behave in natural and engineered ecosystems. Growth dynamics influence nutrient cycling, pollutant degradation, and microbial community interactions.

- Biogeochemical Cycles: Microbes contribute to essential ecological processes like nitrogen fixation, carbon mineralization, and phosphorus solubilization. For example:

- Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter grow in wastewater systems during specific phases to oxidize ammonia to nitrate.

- In composting, microbial activity follows growth phases that correlate with temperature changes (e.g., mesophilic to thermophilic transitions).

- Bioremediation: During soil or water cleanup operations, microbial growth is manipulated to degrade contaminants such as oil spills, heavy metals, or pesticides. The lag phase may be extended if the contaminants are novel to the microbes, necessitating bioaugmentation or biostimulation to reduce adaptation time.

- Wastewater Treatment: In activated sludge systems, understanding microbial growth helps regulate sludge age and nutrient removal efficiency. Specific organisms are cultivated to dominate during the log or stationary phases to maximize breakdown of organic pollutants.

3. Clinical Microbiology

Microbial growth phases have direct implications in infection control, antimicrobial therapy, and disease progression.

- Infection Dynamics: Pathogenic bacteria exhibit distinct behaviors at different growth phases. In the exponential phase, they are most virulent and proliferative, which is when acute symptoms often manifest. In contrast, during the stationary phase, pathogens may form biofilms or enter dormant states:

- Biofilm-forming bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa become antibiotic-tolerant in the stationary phase, contributing to chronic infections in cystic fibrosis or wounds.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis can persist in a non-replicating phase inside macrophages, complicating treatment.

- Antibiotic Efficacy: Most antibiotics, such as β-lactams (e.g., penicillin), are most effective during the log phase when bacteria are actively dividing. Conversely, in the stationary phase, bacteria often exhibit phenotypic resistance or tolerance:

- Antibiotics targeting protein synthesis or DNA replication have reduced activity when cells are metabolically inactive.

- This underscores the importance of timing and dosing strategies in clinical treatment regimens.

- Vaccine Development: Growth phase-specific antigens or virulence factors are often used in subunit vaccines. Understanding when these are expressed informs the design of more effective vaccines.

4. Synthetic Biology and Evolutionary Studies

Controlled manipulation of microbial growth phases is pivotal in synthetic biology, systems biology, and evolutionary microbiology.

- Experimental Evolution: Continuous culture systems like chemostats or turbidostats maintain microbes in a defined growth phase (often log phase), allowing researchers to observe long-term adaptations to environmental pressures:

- Escherichia coli has been evolved over tens of thousands of generations to study mutation accumulation, metabolic rewiring, and resistance mechanisms.

- Metabolic Engineering: Synthetic biologists exploit growth phase transitions to regulate gene expression and optimize metabolic fluxes for the production of target compounds:

- Promoters responsive to nutrient levels (e.g., phosphate limitation) can be used to induce gene expression only in the stationary phase.

- Microbial Consortia Design: Understanding interspecies interactions across growth phases enables the construction of synthetic microbial communities for bioprocessing or biosensing. For instance, one species may produce a metabolite during the stationary phase that serves as a substrate for another species’ exponential growth.

Conclusion

Microbial growth phases—lag, log, stationary, and death—represent a series of physiological transitions that reflect microbial responses to nutrient availability, environmental stress, and metabolic demands. These phases are best studied in batch culture systems, which provide insights into complete life cycle dynamics. On the other hand, continuous culture systems such as chemostats and turbidostats allow for the maintenance of stable growth conditions, making them invaluable tools for controlled studies of microbial physiology, industrial production, and evolutionary experiments.

An in-depth understanding of microbial growth phases and cultivation strategies is foundational for advancing microbial biotechnology, improving clinical outcomes, and addressing global challenges related to antimicrobial resistance, bioremediation, and sustainable production systems. As microbial science continues to evolve, the integration of classical cultivation techniques with modern tools such as genomics, metabolomics, and systems biology will further enhance our capacity to harness the potential of microorganisms for human benefit.

References

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of microorganisms. 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Publishers. USA. Pp.795-796.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA. Pp. 296-299.

Ryan K, Ray C.G, Ahmed N, Drew W.L and Plorde J (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology. Fifth edition. McGraw-Hill Publishers, USA.

Singleton P and Sainsbury D (1995). Dictionary of microbiology and molecular biology, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.