Introduction to Fermentation Processes

Fermentation is a metabolic process by which microorganisms convert organic compounds—primarily carbohydrates—into simpler compounds such as alcohols, acids, and gases. Industrially, fermentation is an essential biotechnological tool utilized for the large-scale production of valuable compounds including antibiotics, enzymes, biofuels, organic acids, and fermented foods. Depending on how substrates are fed and products are removed, fermentation systems are categorized as batch, fed-batch, continuous, or semi-continuous. Among these, continuous and semi-continuous fermentation processes are designed for prolonged, efficient, and often automated production.

Continuous Fermentation: Definition and Principles

Continuous fermentation is defined as a bioprocess in which sterile nutrient medium is continuously supplied to a fermentation vessel, while an equal volume of used medium containing microbial cells, metabolites, and end-products is simultaneously removed. This setup creates a dynamic equilibrium, or “steady state,” where the microbial population and environmental conditions in the bioreactor remain constant over time. Continuous fermentation is also known as an open culture system due to the ongoing exchange of input (nutrients) and output (product broth).

In contrast to batch fermentation, where nutrient depletion and toxic accumulation eventually halt microbial growth, continuous fermentation allows for the sustained exponential growth of microorganisms by constantly replenishing the essential nutrients and removing metabolic waste products. This approach significantly extends the productive lifespan of a microbial culture.

Maintaining Exponential Growth

Continuous fermentation enables the maintenance of a microbial culture in a state of exponential growth for extended durations. This is achieved by controlling the dilution rate—the rate at which fresh medium is added and culture broth is removed. The culture remains in a balanced state where the rate of microbial growth equals the rate of cell removal. This equilibrium ensures that the population density, nutrient concentration, pH, and other critical parameters remain stable.

To achieve optimal continuous culture conditions, the medium is formulated to contain one or more limiting nutrients. This restriction controls the growth rate and prevents the overgrowth of the culture. Unlike batch cultures where nutrients are gradually exhausted, the continuous system keeps the culture in the desired metabolic state by adjusting the feed rate and composition of the incoming medium.

Types of Continuous Culture Systems

The two principal types of continuous fermentation systems used in laboratories and industry are the chemostat and the turbidostat.

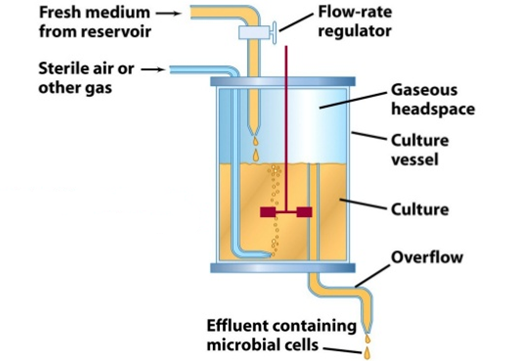

a. Chemostat: A chemostat is a continuous culture device in which the growth rate of microorganisms is controlled by the concentration of a single limiting nutrient (e.g., glucose, nitrogen, phosphate) (Figure 1). The fresh medium containing this limiting nutrient is fed into the bioreactor at a constant rate, while an equal volume of culture broth is withdrawn. The dilution rate (D), defined as the flow rate divided by the culture volume, determines the growth rate of the organisms.

The chemostat maintains a steady-state condition by ensuring that the rate of nutrient supply matches the metabolic activity of the cells. When the dilution rate exceeds the maximum growth rate of the organism, cells are washed out. Conversely, if the dilution rate is too low, cells may overgrow, leading to nutrient exhaustion and metabolic shifts.

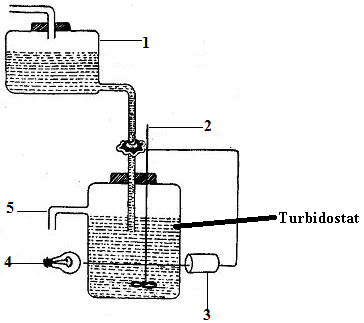

b. Turbidostat: A turbidostat is a continuous culture system designed to maintain a constant cell density or turbidity (Figure 2). It incorporates a photocell or optical sensor that continuously monitors the optical density (OD) or light absorbance of the culture. When the OD exceeds a preset threshold, indicating increased biomass, fresh medium is pumped into the reactor and culture broth is simultaneously removed to dilute the biomass concentration.

Unlike chemostats, turbidostats do not operate with a limiting nutrient. Instead, nutrients are supplied in excess, and microbial growth is governed by the optical feedback system. Turbidostats are particularly useful for studying fast-growing organisms or dynamic responses to environmental changes, as they allow the culture to grow at its maximum specific growth rate.

Advantages of Continuous Fermentation

Continuous fermentation systems offer numerous advantages over traditional batch and fed-batch processes, making them particularly attractive for industrial and research applications. Some of the advantages are as follows:

1. High Productivity:

One of the most significant benefits of continuous fermentation is the ability to maintain microbial cells in the exponential (logarithmic) growth phase. In this phase, cells exhibit peak metabolic activity and optimal product synthesis. Because fresh nutrients are constantly supplied while waste products are removed, the system supports uninterrupted production. This leads to increased productivity per unit volume and time, often surpassing what is achievable in batch processes.

2. Reduced Downtime:

Unlike batch systems, where the reactor must be regularly emptied, cleaned, sterilized, and re-inoculated, continuous fermenters remain operational for extended periods. These time-consuming procedures are significantly reduced or completely eliminated, improving process efficiency and reducing labor, utility, and equipment wear costs.

3. Consistent Product Quality:

Continuous systems operate under steady-state conditions, ensuring that environmental parameters such as pH, temperature, nutrient concentration, and oxygen levels remain constant. This stability results in a more uniform product with minimal variation in concentration, composition, or bioactivity—an essential attribute for pharmaceutical, food, and chemical industries where quality control is paramount.

4. Enhanced Automation and Control:

Modern continuous fermenters are equipped with advanced sensors and control systems that allow for real-time monitoring and regulation of process variables. Parameters like biomass concentration, dissolved oxygen, pH, and nutrient levels can be precisely adjusted, ensuring optimal conditions throughout the fermentation.

5. Ideal for Research and Development:

Continuous cultures are particularly useful for investigating microbial physiology, metabolism, and genetics. The ability to maintain stable conditions over prolonged periods makes them ideal for long-term studies on genetic stability, mutation rates, adaptive evolution, and metabolic flux, providing valuable insights into microbial behavior.

Limitations of Continuous Fermentation

While continuous fermentation offers numerous advantages such as high productivity, consistent product quality, and efficiency, it also presents several limitations and operational challenges that can affect its widespread industrial adoption. Some of the limitations are as follows:

1. Contamination Risk:

One of the major disadvantages of continuous fermentation is the increased risk of microbial contamination. Since the process is designed to operate over extended periods—sometimes weeks or months—any contamination, even at a low level, can proliferate and compromise the entire culture. Unlike batch fermentation, where each cycle starts with a freshly sterilized vessel, continuous systems offer fewer opportunities for full sterilization between runs, making contamination control more complex and essential.

2. System Complexity:

The continuous mode requires all associated systems—such as nutrient feed, waste removal, product recovery, and sterilization—to operate seamlessly and simultaneously. This demands sophisticated monitoring, automation, and control mechanisms. As a result, the infrastructure and maintenance costs are significantly higher than those for batch or semi-continuous processes. A failure in any single component, especially downstream processes, can halt the entire operation, leading to loss of productivity and resources.

3. Genetic Instability and Strain Displacement:

Over time, the desired production strain may undergo genetic mutations or be displaced by faster-growing, less efficient variants. This problem is particularly acute in systems lacking proper monitoring and selection pressure. The evolution of these less productive strains can lead to a decline in product yield and process efficiency.

4. Biofilm Formation and Cell Aggregation:

Wall growth, biofilm formation, and microbial aggregation within the bioreactor can reduce effective volume, disrupt steady-state conditions, and interfere with nutrient flow and product removal. These phenomena also pose challenges in cleaning and process control.

5. Organism Limitations:

Continuous fermentation is not suitable for all microorganisms. Filamentous fungi, mycelial organisms, and other shear-sensitive or highly viscous cultures are difficult to cultivate continuously due to issues with mixing, aeration, and clogging of equipment.

Semi-Continuous Fermentation

Semi-continuous fermentation, also known as repeated batch or quasi-continuous fermentation, represents a hybrid between batch and continuous processes. In this method, fermentation is carried out in cycles where a portion of the culture medium is periodically removed and replaced with fresh nutrient medium.

This periodic renewal of medium enables the culture to remain active for an extended duration while avoiding the full complexities of a truly continuous system. Unlike batch fermentation, where all the substrate is provided at once, and unlike continuous fermentation, where inflow and outflow are constant, semi-continuous processes offer more operational flexibility.

Operational Features of Semi-Continuous Fermentation

Semi-continuous fermentation, also known as repeated-batch fermentation, represents a hybrid approach that combines elements of both batch and continuous fermentation systems. In this method, the fermentation process is typically carried out in a sequence of operational cycles. At the end of each cycle, a defined proportion—usually ranging from 30% to 70%—of the fermented broth is withdrawn from the fermenter. This removed volume contains a mixture of microbial cells, metabolites, and spent medium. Immediately afterward, an equal volume of fresh sterile nutrient medium is introduced into the vessel to replenish the system and sustain microbial activity.

The renewed medium replenishes essential nutrients that have been consumed during fermentation, while also diluting accumulated inhibitory by-products that might otherwise slow or stop microbial growth. This periodic replenishment enables the microbial population to remain in a relatively stable and active growth phase across multiple cycles. Although it does not achieve the same level of steady-state control as continuous fermentation, semi-continuous systems can effectively prolong the productive phase of microbial cultures without the need for full reactor shutdowns between cycles.

One of the key operational advantages of semi-continuous fermentation is its flexibility. It allows operators to adjust withdrawal and refill rates based on process parameters such as biomass concentration, product yield, and nutrient availability. Additionally, because the fermenter is not emptied entirely between cycles, the system retains an active microbial population, minimizing lag time that typically follows inoculation in traditional batch processes.

This fermentation mode is particularly beneficial in processes where regular rejuvenation of the culture is needed due to declining metabolic activity or accumulation of toxic metabolites. Semi-continuous systems are commonly applied in the production of microbial biomass, biofuels (such as ethanol), organic acids (e.g., lactic acid), and certain secondary metabolites including antibiotics and vitamins. It also finds use in food and beverage fermentations where batch-to-batch consistency is crucial, yet continuous operation may not be feasible.

Overall, semi-continuous fermentation offers a balance between the operational simplicity of batch systems and the efficiency of continuous processes. Its cyclical nature supports sustained productivity, enhances process control, and provides a useful compromise where full continuous automation is either impractical or cost-prohibitive.

Advantages of Semi-Continuous Fermentation

Semi-continuous fermentation offers a balanced approach between batch and fully continuous systems, providing several operational and technical benefits that make it suitable for various industrial and research applications. Some of the advantages are as follows:

1. Operational Flexibility:

Semi-continuous systems allow for greater control over the fermentation process, as operators can adjust the timing, volume of medium exchanged, and nutrient composition during each cycle. This flexibility enables process optimization based on the specific growth requirements of the microorganism or changes in production targets. It also facilitates more precise modulation of environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, and oxygen levels between cycles.

2. Reduced Risk of Contamination:

Because semi-continuous fermentation is not a fully open system, and nutrient/media addition occurs intermittently rather than constantly, the risk of introducing contaminants is significantly lower compared to continuous systems. Each cycle allows for inspection and potential cleaning or intervention, thus enhancing process hygiene and reliability over longer operational periods.

3. Simplicity and Cost-Effectiveness:

Semi-continuous fermentation systems generally require simpler infrastructure and less automation compared to continuous systems. They do not demand advanced real-time monitoring equipment, making them more economically viable for small- to medium-scale production setups, educational laboratories, or experimental applications where resources may be limited.

4. Strain Stability and Maintenance:

The periodic renewal of culture medium helps in maintaining the physiological stability of microbial strains. This prevents issues such as genetic drift or the outgrowth of mutant or contaminant strains, ensuring consistent productivity and product quality over multiple fermentation cycles.

Limitations of Semi-Continuous Fermentation

Despite its hybrid nature and certain operational flexibilities, semi-continuous fermentation has several drawbacks that limit its broader industrial application. Some of the limitations are as follows:

- Lower Productivity: In comparison to fully continuous fermentation systems, semi-continuous processes often exhibit reduced overall productivity. This is primarily due to the interruptions and downtime required for partial withdrawal of spent medium and the replenishment of fresh nutrients. These pauses, though shorter than in traditional batch systems, still disrupt the steady-state production rhythm that continuous systems maintain.

- Labor Intensive: Semi-continuous fermentation usually requires manual or semi-automated intervention at regular intervals to remove a portion of the culture broth and add fresh medium. This repeated handling increases labor demands and makes the process less efficient and less scalable for high-throughput industrial operations, especially those aiming for automation and minimal human oversight.

- Process Inconsistencies: Because each cycle involves changes in medium composition and possibly environmental conditions, variations can occur between cycles. These inconsistencies may lead to fluctuations in microbial activity, product yield, biomass concentration, and overall product quality, making it harder to maintain tight control over critical process parameters.

- Limited Application Scope: Semi-continuous systems may not be suitable for fermentations that require stringent maintenance of environmental conditions (such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) or for organisms sensitive to changes in nutrient composition. For such processes, even minor disturbances during exchange cycles could negatively impact cell viability, metabolic balance, or product formation.

As a result, semi-continuous fermentation is typically preferred for smaller-scale operations or applications where moderate variability can be tolerated.

Applications of Continuous and Semi-Continuous Fermentation

Continuous and semi-continuous fermentation systems have gained widespread use across numerous sectors of biotechnology due to their ability to maintain microbial cultures in a productive state over extended periods. These systems are particularly beneficial when consistent product quality, high yields, and reduced production costs are desired. Their applications span pharmaceuticals, bioenergy, food production, and environmental management.

1. Pharmaceuticals

Continuous fermentation is instrumental in the production of antibiotics, such as penicillin, streptomycin, and tetracycline. The stable conditions maintained in continuous systems ensure consistent metabolite production and improve overall process efficiency. These systems are also employed in vaccine production, especially for viral vaccines grown in microbial or mammalian cell cultures. Furthermore, industrial enzymes like proteases, amylases, and cellulases are often manufactured through semi-continuous processes, which balance operational flexibility and productivity.

2. Biofuels

The production of bioethanol, biobutanol, and biodiesel relies heavily on microbial fermentation. Continuous fermentation offers advantages in large-scale ethanol production by yeast or bacteria, as it allows for uninterrupted conversion of sugars to fuel. Semi-continuous systems are also used when strain stability and process control are crucial, particularly in pilot-scale operations or when dealing with lignocellulosic biomass.

3. Food and Beverage Industry

In the food industry, these fermentation modes are used for the cultivation of lactic acid bacteria in yogurt and cheese production, as well as for fermented beverages like beer and wine. Continuous systems help maintain the viability and performance of starter cultures, while semi-continuous methods are useful in processes that require periodic intervention or mixed cultures.

4. Environmental Biotechnology

Continuous fermentation is widely applied in wastewater treatment, where microbial consortia degrade organic pollutants in bioreactors. Semi-continuous systems are commonly used in bioremediation, such as the treatment of contaminated soils and effluents, where a balance between microbial activity and contaminant load is essential.

5. Industrial Biotechnology

The production of organic acids (e.g., citric, lactic, and acetic acids), amino acids (e.g., glutamate, lysine), and recombinant proteins (e.g., insulin, growth hormones) often utilizes continuous or semi-continuous cultures. These approaches help maintain a steady output of desired metabolites and allow for efficient scaling of production.

Conclusion

Continuous and semi-continuous fermentation processes represent essential strategies in industrial microbiology and biotechnology. While continuous fermentation offers high productivity, process automation, and consistent product quality, it demands careful control and is susceptible to contamination and strain degeneration. Semi-continuous fermentation offers a practical compromise, combining some advantages of batch and continuous systems while minimizing operational complexity and contamination risks.

Understanding the underlying principles, operational parameters, advantages, and limitations of each fermentation type is crucial for selecting the most appropriate system based on the specific production goals, microbial strain characteristics, and industrial scale. As biotechnology advances, the integration of real-time monitoring, adaptive control systems, and synthetic biology tools will further enhance the efficiency and applicability of continuous and semi-continuous fermentation processes.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.