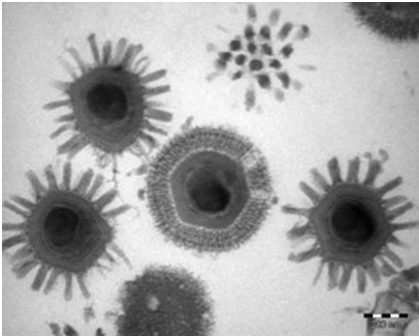

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne viral disease first described during an outbreak in southern Tanzania in 1952. It is an RNA virus that belongs to the alphavirus genus of the family Togaviridae. The name “chikungunya” derives from a word in the Kimakonde language, meaning “to become contorted”, and describes the stooped appearance of sufferers with joint pain (arthralgia).

Key facts about chikungunya infection

- Chikungunya is a viral disease transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes. It is caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV).

- A CHIKV infection causes fever and severe joint pain. Other symptoms include muscle pain, joint swelling, headache, nausea, fatigue and rash.

- Joint pain associated with chikungunya is often debilitating, and can vary in duration.

- There is currently no vaccine or specific drug against the virus. The treatment is focused on relieving the disease symptoms.

- The disease mostly occurs in Africa, Asia and the Indian subcontinent. However a major outbreak in 2015 affected several countries of the Region of the Americas, and sporadic outbreaks are seen elsewhere.

- The disease shares some clinical signs with dengue and Zika, and can be misdiagnosed in areas where they are common.

- Severe cases and deaths from chikungunya are very rare and are almost always related to other existing health problems.

- Due to the challenges in accurate diagnosis for chikungunya, the is no real estimate for the number of people affected by the disease globally on an annual basis.

- The proximity of mosquito breeding sites to human habitation is a significant risk factor for chikungunya.

Distribution and outbreaks of chikungunya

Chikungunya virus was first identified in Tanzania in 1952 and for the following ~50 years was isolated and caused occasional outbreaks in Africa and Asia. Since 2004, chikungunya has spread rapidly and been identified in over 60 countries throughout Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas.

Starting in 2004, an outbreak in Kenya spread to surrounding locations in the Indian Ocean. In the two years following, around 500 000 cases were reported; on La Reunion Island, more than 1/3 of the population became infected. The epidemic then spread from the Indian Ocean to India, where it persisted for a number of years, infecting almost 1.5 million people. Viremic travellers saw the virus spread to Indonesia, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand.

In 2007, local transmission was reported for the first time in Europe, in a localized outbreak in north-eastern Italy where 197 cases recorded. This outbreak confirmed that mosquito-borne outbreaks vectored by Aedes Albopictus are plausible in Europe. 2010 saw the virus continue to cause illness in South East Asia, and another outbreak was observed in La Reunion, in the Indian Ocean. Viremic travellers again imported the virus into Europe, as well as the USA and Taiwan.

In the year 2013, the first documented outbreak of chikungunya with autochthonous transmission in the Americas occurred; it started with two laboratory-confirmed, autochthonous cases were reported in the French region of the Caribbean island of St Martin and it spread rapidly throughout the region. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in this same year were reported 72 cases, with France, the UK, and Germany observing the most cases.

In 2014, Europe faced its highest chikungunya burden, with almost 1 500 cases. Again France and the UK were more affected. France also confirmed 4 cases of locally-acquired chikungunya infection in the south of the country. Late that year, outbreaks were reported in the Pacific islands including the Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Samoa, American Samoa, French Polynesia and Kiribati. More than 1 million suspected cases were also reported to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) regional office that year.

In 2015, ECDC reported a decline in chikungunya cases from the 2014, down to 624 cases. WHO’s African Regional Office (AFRO) recorded an outbreak in Senegal, representing the first active circulation in the area in five years. In the Americas, there were 693 489 suspected and 37 480 confirmed cases of chikungunya reported to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) regional office, of which Colombia had the highest burden with 356 079 suspected cases. This burden in the Americas however, was significantly less than in the previous year.

In 2016, there was a total of 349 936 suspected and 146 914 laboratory-confirmed cases reported to the PAHO regional office, being half the burden compared to the previous year. Countries reporting most cases were Brazil, Bolivia and Colombia (with around 300 000 suspected cases between them). Argentina reported the first evidence of autochthonous transmission of chikungunya, following an outbreak of more than 1 000 suspected cases. In Africa, Kenya reported an outbreak of chikungunya resulting in more than 1 700 suspected cases, while in Somalia, the town of Mandera was hard hit, with about 80% of the population affected by chikungunya. Chikungunya cases in India were approaching 65 000. European case reports remained below 500.

In 2017, ECDC reported a total of 10 countries, with 548 cases with chikungunya, of which 84% were confirmed cases. Italy bore more than 50% of the chikungunya burden. Autochthonous cases were again reported in Europe (France and Italy) for the first time since 2014.

As in previous years, Asia and the Americas were the regions most affected by chikungunya. Pakistan faced a persistent outbreak that started the previous year and reported 8 387 cases, while India suffered with 62 000 cases. In the Americas and the Caribbean were reported 185 000 cases; the cases in Brazil accounted for >90% in the region of the Americas. Chikungunya outbreaks were also reported in Sudan (2018), Yemen (2019) and more recently in Cambodia and Chad (2020)

Transmission of chikungunya virus

Chikungunya virus is transmitted between humans via mosquitoes. When a naïve (uninfected) mosquito feeds upon a viremic person (someone who has the virus circulating in their blood), the mosquito can pick up the virus as it ingests the blood. The virus then undergoes a period of replication in the mosquito, before which time it can then be transmitted back to a new, naïve host, when the mosquito next feeds. The virus again begins to replicate in this newly infected person and amplify to high concentrations. If a mosquito feeds on them during the time they have virus circulating in their blood, the mosquito can pick up the virus, and the transmission cycle begins again.

Within the mosquito, the virus replicates in the mosquito midgut. It then disseminates to secondary tissues, including the salivary glands. CHIKV can be transmitted to a new, naïve host more quickly than for other mosquito-borne viruses; laboratory experiments have demonstrated virus can be detected in saliva as little as 2-3 days after the blood meal1. This suggests that the complete transmission cycle from human to mosquito, and back to humans can occur in well under a week. Once infectious, the mosquito is believed to be capable of transmitting virus for the rest of its life.

Most commonly, the mosquitoes involved in the transmission cycle are Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Both species can also transmit other mosquito-borne viruses, including dengue and Zika fever viruses.

Vector Ecology of the chikungunya virus

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne viral disease transmitted to humans following bite from an Aedes mosquito, particularly the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Both Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus have been implicated in large outbreaks of chikungunya. Whereas Ae. aegypti is confined within the tropics and sub-tropics, Ae. albopictus also occurs in temperate and even cold temperate regions. These mosquitoes can be found biting throughout daylight hours, though there may be peaks of activity in the early morning and late afternoon. Both species are found biting outdoors, but Ae. aegypti will also readily feed indoors.

The Ae. albopictus species thrives in a wider range of water-filled breeding sites than Ae. aegypti, including coconut husks, cocoa pods, bamboo stumps, tree holes and rock pools, in addition to artificial containers such as vehicle tyres and saucers beneath plant pots. This diversity of habitats explains the abundance of Ae. albopictus in rural as well as peri-urban areas and shady city parks. In recent decades Ae. albopictus has spread from Asia to become established in areas of Africa, Europe and the Americas. The geographic spread of this competent vector, as well as the increase in frequency of virus importations means that local virus transmission in previously unaffected areas is more likely.

Ae. aegypti is more closely associated with human habitation and uses indoor breeding sites, including flower vases, water storage vessels and concrete water tanks in bathrooms, as well as the same artificial outdoor habitats as Ae. albopictus.

In Africa several other mosquito vectors have been implicated in disease transmission, including species of the A. furcifer-taylori group and A. luteocephalus. There is evidence that some animals, including non-primates, rodents, birds and small mammals, may act as reservoirs of the virus, allowing re-emergence of the virus after periods of inactivity in humans.

Disease characteristics (signs and symptoms) of chikungunya infection

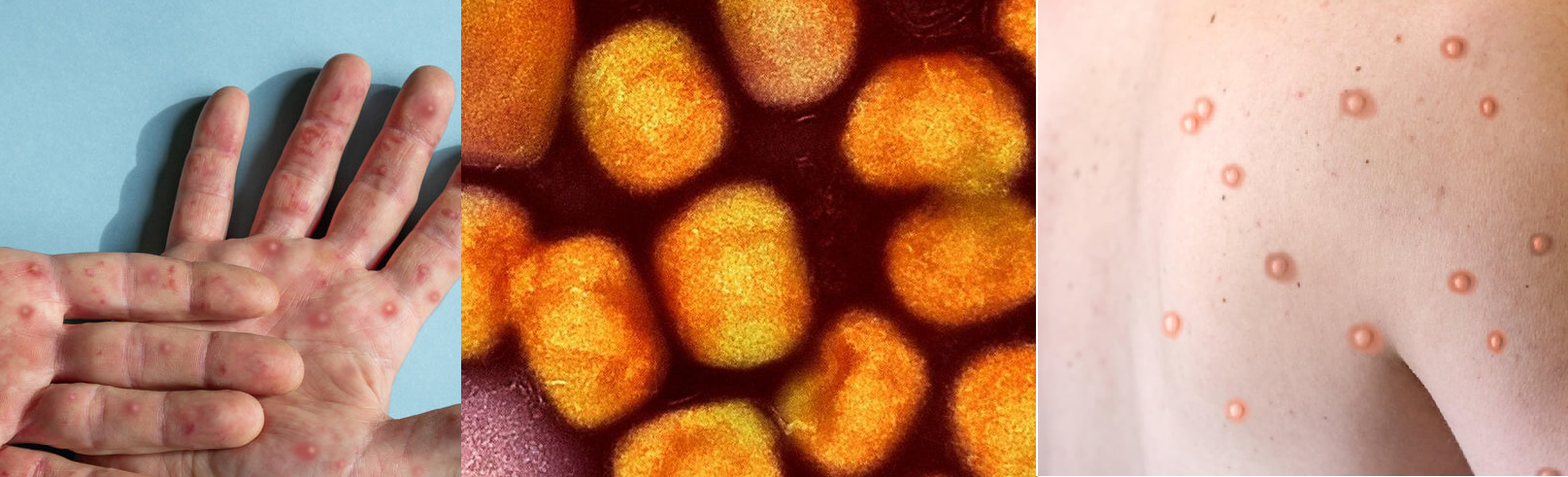

After the bite of an infected mosquito, onset of illness usually occurs 4-8 days later (but can range from 2-12 days). Chikungunya is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, frequently accompanied by joint pain. The joint pain is often very debilitating; it usually lasts for a few days, but may be prolonged for weeks, months or even years. Hence, the virus can cause acute, subacute or chronic disease. Other common signs and symptoms include muscle pain, joint swelling, headache, nausea, fatigue and rash.

The symptoms in infected individuals are usually mild and the infection may go unrecognized or may be misdiagnosed. The symptoms can also be similar to other arboviruses; in areas where there is co-circulation, chikungunya is often misdiagnosed as dengue2. Unlike dengue however, chikungunya rarely progresses to become life threatening.

Occasional cases of ophthalmological, neurological and heart complications have been reported with chikungunya virus infections, as well as gastrointestinal complaints. Serious complications are not common, but in older people with other medical conditions, the disease can contribute to the cause of death.

Most patients recover fully from the infection, but in some cases joint pain may persist for several months, or even years. Once an individual is recovered, they are likely to be immune from future infections.

Diagnostics of chikungunya infection

Several methods can be used for diagnosis of chikungunya virus infection. Serological tests, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), may confirm the presence of IgM and IgG anti-chikungunya antibodies. IgM antibody levels are highest 3 to 5 weeks after the onset of illness and persist for about 2 months.

The virus may be directly detected in the blood during the first few days of infection as well. As such, samples collected during the first week of illness should be tested by both serological and virological methods (particularly reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)). Various RT–PCR methods are available but with variable sensitivity. Some are suited to clinical diagnostics. RT–PCR products from clinical samples may also be used for genotyping of the virus, allowing comparisons with virus samples from various geographical sources.

Treatment of chikungunya infection

There is no specific antiviral drug treatment for chikungunya. The clinical management targets primarily to relieving the symptoms, including the joint pain using anti-pyretics, optimal analgesics, drinking plenty of fluids and general rest.

Medicines such as paracetamol or acetaminophen are recommended to pain relief and reducing fever. Given the similarity of symptoms between chikungunya and dengue, in areas where both viruses circulate, suspected chikungunya patients should avoid using aspirin or Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) until which time a dengue diagnosis is ruled out (because in dengue, these medicines can increase the risk of bleeding).

Vaccination against chikungunya infection

There is no commercial vaccine available to protect against chikungunya virus infection. While there are several vaccine strategies being pursued (as of mid-2020), of which some are in various stages of clinical trials3, they are still several years away from being licensed and available to the public. Prevention of infection by avoiding mosquito bites is the best protection.

Prevention and control of chikungunya infection in human population

If you know you have chikungunya, avoid getting further mosquito bites during the first week of illness. Virus may be circulating in the blood during this time, and therefore you may transmit the virus to new mosquitoes, who may in turn infect other people.

The proximity of mosquito vector breeding sites to human habitation is a significant risk factor for chikungunya as well as for other diseases that Aedes mosquito species transmit. At present, the main method to control or prevent the transmission of chikungunya virus is to combat the mosquito vectors. Prevention and control relies heavily on reducing the number of natural and artificial water-filled container habitats that support breeding of the mosquitoes. This requires mobilization of affected and at-risk communities, to empty and clean containers that contain water on a weekly basis to inhibit mosquito breeding and the subsequent production of adults. Sustained community efforts to reduce mosquito breeding can be an effective tool to reduce vector populations.

During outbreaks, insecticides may be sprayed to kill flying mosquitoes, applied to surfaces in and around containers where the mosquitoes land, and used to treat water in containers to kill the immature larvae. This may also be performed by health authorities as an emergency measure to control the mosquito population.

For protection during outbreaks of chikungunya, clothing which minimizes skin exposure to the day-biting vectors is advised. Repellents can be applied to exposed skin or to clothing in strict accordance with product label instructions. Repellents should contain DEET (N, N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide), IR3535 (3-[N-acetyl-N-butyl]-aminopropionic acid ethyl ester) or icaridin (1-piperidinecarboxylic acid, 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-methylpropylester).

For those who sleep during the daytime, particularly young children, or sick or older people, insecticide-treated mosquito nets afford good protection, because the mosquitoes that transmit chikungunya feed primarily during the day. Basic precautions should be taken by people travelling to risk areas and these include use of repellents, wearing long sleeves and pants and ensuring rooms are fitted with screens to prevent mosquitoes from entering.

The response of the World Health Organization (WHO) to chikungunya infection around the world

WHO responds to chikungunya in the following ways:

- supports countries in the confirmation of outbreaks through its collaborating network of laboratories;

- provides technical support and guidance to countries for the effective management of mosquito-borne disease outbreaks;

- reviews the development of new tools, including insecticide products and application technologies;

- formulating evidence-based strategies, policies, and outbreak management plans;

- providing technical support and guidance to countries for the effective management of cases and outbreaks;

- supporting countries to improve their reporting systems;

- providing training on clinical management, diagnosis and vector control at the regional level with some of its collaborating centres;

- publishing guidelines and handbooks on epidemiological surveillance, laboratory, clinical case management and vector control for Member States.

Source:

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.