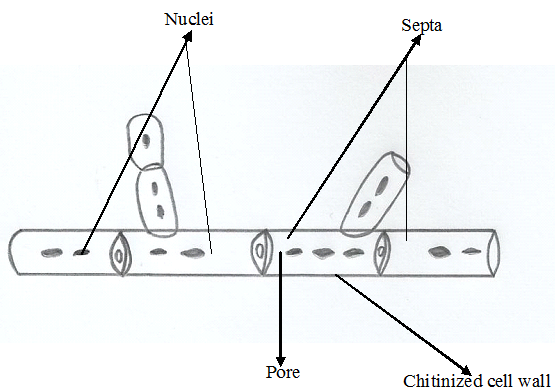

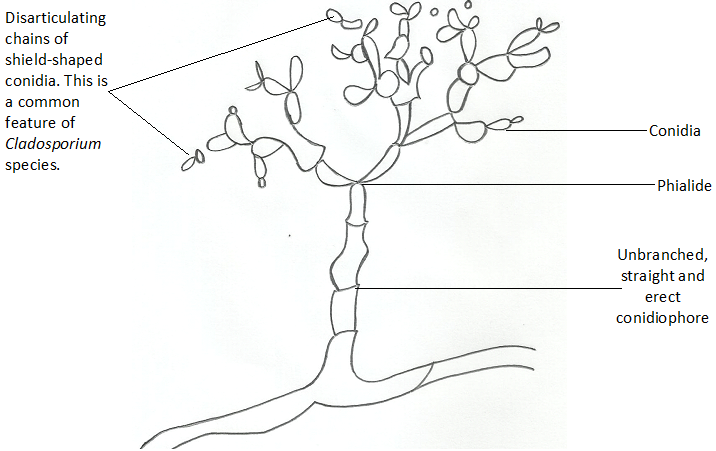

- Penicillum: Penicillium is a genus of ascomycetous fungi. This genus of fungi is of major importance to man; and they have application in drug production and even in food production. Penicillin is an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infection, and it is naturally sourced from a member of the Penicillium genus known as Penicillium chrysogenum. Penicillium species are recognized by their dense brush-like spore-bearing structures called penicilli (singular: penicillus). The conidiophores are simple or branched and are terminated by clusters of flask-shaped phialides.

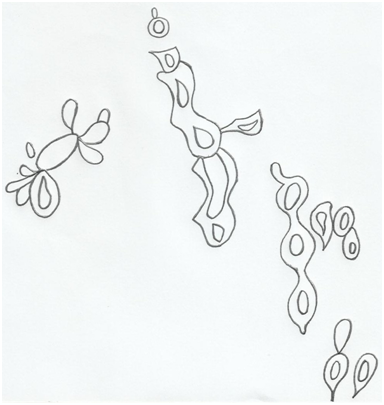

The spores (conidia) are produced in dry chains from the tips of the phialides, with the youngest spore at the base of the chain (Figure 1). Penicillium is found in the soil, decaying vegetation, air and they are common contaminants on various substances. Penicillium causes food spoilage, and it colonizes leather objects. It is an indicator organism for dampness indoors. Some penicillium species are known to produce toxic compounds known as mycotoxins. Some species of Penicillium reproduce sexually by means of asci and ascospores produced within small stony stromata.

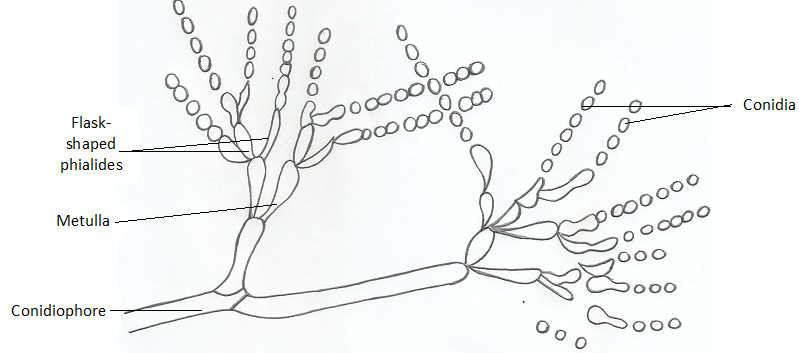

- Scopulariopsis: Fungi in the genus Scopulariopsis are common soil saprophytes. This genus contains fungal species that are anarmorphic in nature; and they are also pathogenic to animals. They have asexual forms or stages of reproduction – which allow them to form conidia (Figure 2). Scopulariopsis species are commonly found in soil, dry walls, cellulose board, wallpaper, wood, mattress dust, decaying wood, and various other plant and animal products.

Examples of fungal species in the genus Scopulariopsis include S. asperula, S. brumptii and S. brevicaulis. Scopulariopsis species are dermatomycotic molds and they have been associated with onychomycosis (i.e. fungal infection of the nails). Scopulariopsis species are common fungal contaminants in both the indoors and outdoors but they also cause mycosis in humans, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Generally, Scopulariopsis species are known as saprobes because they feed on dead or decayed organic matter; and thus they undergo a saprotrophic mode of nutrition.

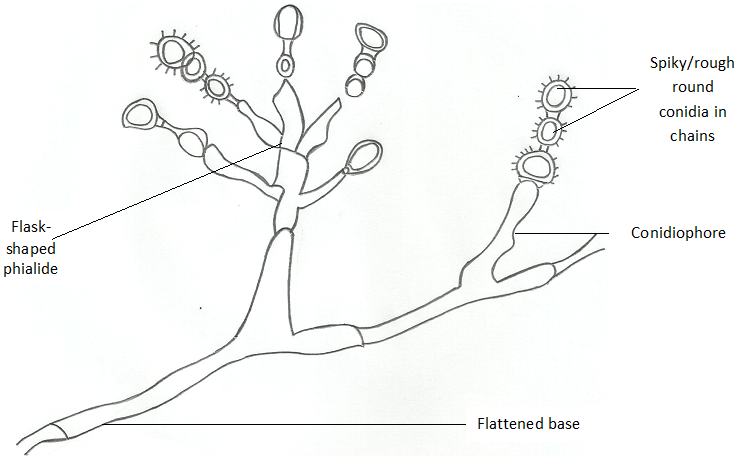

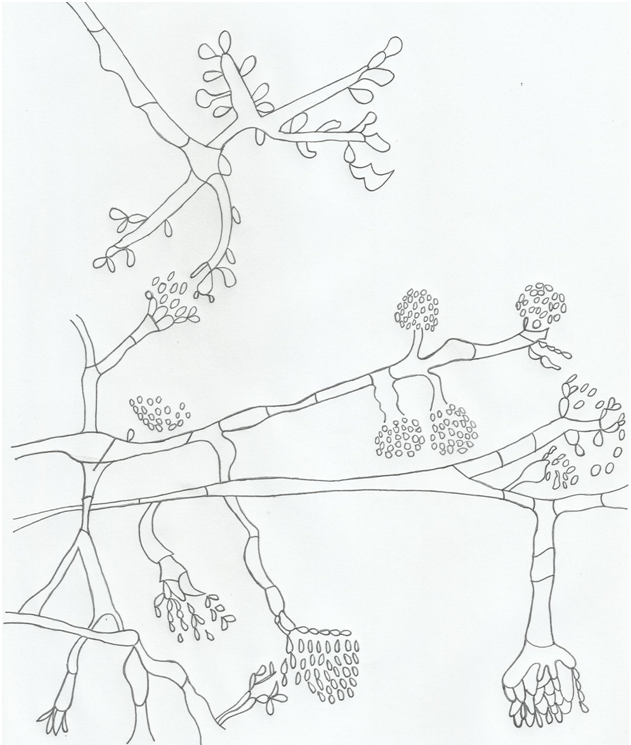

- Cladosporium: Thisis a genus of fungi that contain fungal organisms commonly found in indoor and outdoor environments. They are commonly found in the air and on surfaces such as wallpaper or carpet indoors, especially where moisture is present. Fungi in this genus parasitize plants, animals and other fungi. Cladosporium species rarely cause disease in humans but they can cause mycoses of the skin and toenails occasionally.

Morphologically, they form brown or black colonies on their substrates, and they have dark-pigmented conidia that are formed in simple or branching chains (Figure 3). Cladosporium species are significant allergens. In large amounts, spores of Cladosporium species can severely affect people with asthma and respiratory diseases who inhale these spores. Though they rarely cause human infections, mycoses of the skin, eye, sinus, and brain have been previously reported.

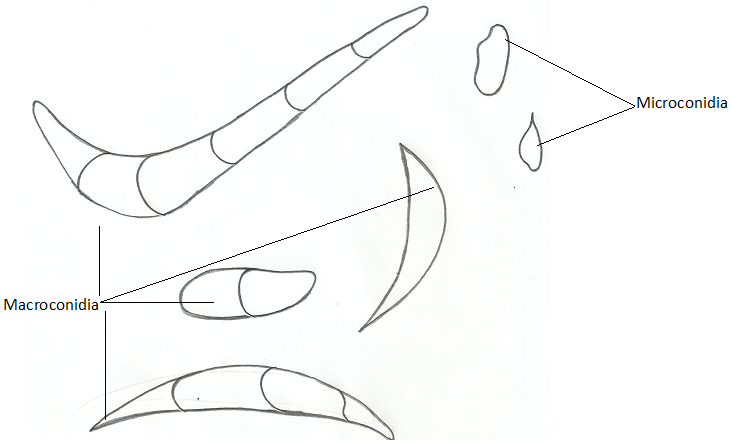

- Fusarium: Fusarium species are filamentous fungi that are abundant in the soil, and they form both large conidia (macroconidia) and small conidia known as microconidia (Figure 4). Some fungi form phialides, from which their conidia develop, and this is applicable in fungi that undergo asexual reproduction such as F. solani. Phialidesare bottle-shaped structures within which or from which conidia develop (Figure 5). Fungi in this group are known for their ability to form or produce toxins that have medical significance.

Fusarium species are toxigenic in nature, and the mycotoxins produced by these fungi are often associated with animal and human diseases. For example, Fusarium species cause mycoses of the nails (onychomycosis) and cornea (keratomycosis); and they cause serious infections in immunocompromised individuals. Many species of Fusarium found in the soil are harmless, and they undergo a saprotrophic mode of nutrition. F. moniliforme, F. solani, and F. oxysporum are typical examples of fungi in the genus Fusarium. Fusarium species produce mycotoxins in cereal crops that can affect both human and animal health if they enter the food chain.

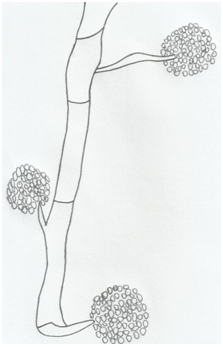

- Fonsecaea: Fonsecaea is a genus that contains fungi implicated in causing chromoblastomycosis. Chromoblastomycosis is a localized fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Human infection usually occurs through the traumatic implantation of conidia or hyphal forms of the organism. Fonsecaea species are sporulating in nature, and thus form spores or conidia used for reproduction and dispersal (Figure 6).

Fonsecaea pedrosoi is a typical example of fungus in the genus Fonsecaea; and the organism grows as a soil saprotroph. They can also be found on trees and plants. Other fungal species in the genus Fonsecaea include F. nubica and F. monophora; and these fungi are pathogenic. People who work in occupation where dusts particles can become easily aerosolized (for example farmers) especially in endemic areas of the disease can easily develop chromoblastomycosis.

- Exophiala: Exophiala is a fungal genus that contains fungi knonwn as black yeasts. Typical example is Exophiala dermatitidis – which is a thermophilic black yeast that rarely cause infection in humans. However, people with compromised immune system are mostly at risk of acquiring infection with Exophiala dermatitidis. Exophiala dermatitidis is found in low abundance in nature; and the fungus occurs in the soil in decaying matter.

Exophiala species can be found in wet and moist man-made environments such as in pools. Exophiala dermatitidis is an anarmorphic fungus that forms many conidia. The hyphal forms of E. dermatitidis shows fertile sterigmates of hyphae & conidiophore which are surrounded by spores or conidia during growth (Figure 7). E. dermatitidis also form black yeast forms on substrates (Figure 8). Fungi in the Exophiala genus cause subcutaneous and cutaneous infection in endemic regions.

References

Anaissie E.J, McGinnis M.R, Pfaller M.A (2009). Clinical Mycology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. London.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Black, J.G. (2008). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley & Sons.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA.

Brown G.D and Netea M.G (2007). Immunology of Fungal Infections. Springer Publishers, Netherlands.

Calderone R.A and Cihlar R.L (eds). Fungal Pathogenesis: Principles and Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002.

Chakrabarti A and Slavin M.A (2011). Endemic fungal infection in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol, 9:337-344.

Champoux J.J, Neidhardt F.C, Drew W.L and Plorde J.J (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. McGraw Hill Companies Inc, USA.

Chemotherapy of microbial diseases. In: Chabner B.A, Brunton L.L, Knollman B.C, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Germain G. St. and Summerbell R (2010). Identifying Fungi. Second edition. Star Pub Co.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999). Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev, 12:501–517.

Gillespie S.H and Bamford K.B (2012). Medical Microbiology and Infection at a glance. 4th edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, UK.

Larone D.H (2011). Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. Fifth edition. American Society of Microbiology Press, USA.

Levinson W (2010). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology. Twelfth edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies, USA.

Madigan M.T., Martinko J.M., Dunlap P.V and Clark D.P (2009). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 12th edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings Inc, USA.

Mahon C. R, Lehman D.C and Manuselis G (2011). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Fourth edition. Saunders Publishers, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.