Spontaneous generation (abiogenesis) is the mistaken hypothesis that living organisms are capable of being generated from non-living things. Mankind for many centuries (even till the time of Aristotle in 4th century BC) previously believed that non-living things such as meat and even decaying organic matter can generate living things (e.g. maggot). The belief that life can emanate from non-life was widely accepted as at the time even by scientists who could have experimented on it to either disprove or accept the theory.

Nevertheless several scientists (including John Needham, Francesco Redi, John Tyndall and Louis Pasteur) as at the time abiogenesis was accepted were curious on how the concept of abiogenesis was true and relevant. This led this notable scientist’s to conduct series of experiments which led to the final disapproval of the theory of spontaneous generation.

Spontaneous generation (though an obsolete biological theory) sparked a lot of controversies for many years in the world; and scientists, religious leaders and especially philosophers had different views as to how life originated. A wider part of the society as at the time believed that life could originate from nothing especially from non-living things or some kind of vital forces that were present in decomposing organic matter.

The concept of spontaneous generation was very appealing to some scientists and even philosophers as at the time who believed strongly that life originated from non-life, but religious leaders fought against it because they believed that life originated from a supernatural being. In the subsequent pages, we shall discover that spontaneous generation does not occur, and that life does not emanate from non-life but from pre-existing life as exemplified by the notable works of Louis Pasteur amongst others.

How did life originated? The increase in knowledge, human’s quest for understanding life and the development of the scientific method gave man a better perspective of his environment and how the organisms in it (inclusive of microorganisms) directly or indirectly affect him. Previously, people believed so many things even when they did not conduct experiment to know if what they observed in their immediate natural environment is true or not. The theory of spontaneous generation held-sway for a long period of time before it was challenged and disproven through the experimental works of some notable scientists like Louis Pasteur. It is noteworthy that the scientists who attempted to disprove abiogenesis carried out their experiments or testing based on the scientific method.

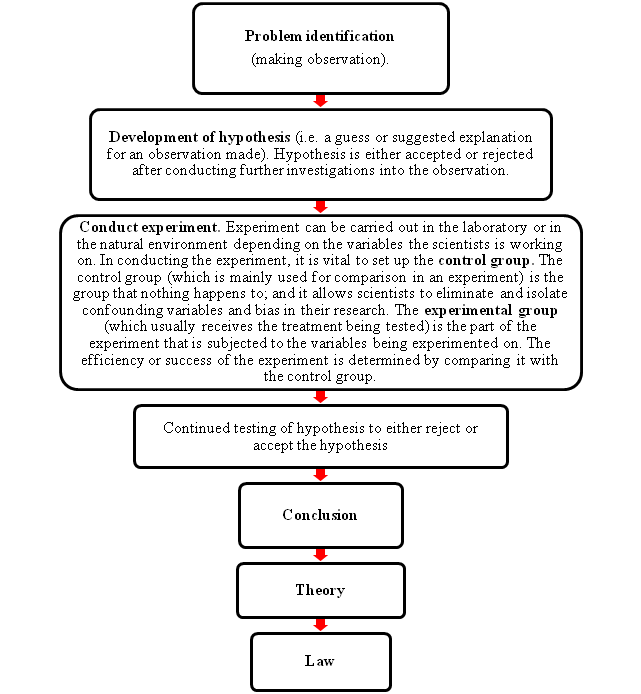

Scientific method is the general approach that involves series of systematic steps or modus operandi used by scientists (including microbiologists) to conduct research. This methodical approach enables scientists (anywhere in the world) to conduct make scientific inquiries and arrive at conclusive answers to their observations or questions; and scientific method is a universally accepted approach of conducting research by scientists. The basic steps involved in the scientific method (which may vary depending on the experimentation) are elaborated in Figure 1.

Before it was disproved, people believed that life originated from non-living matter, a biological phenomenon known as spontaneous generation. Biogenesis is an alternative hypothesis to spontaneous generation; and it postulates that living organisms originated from pre-existing living things. Those who supported the claims of spontaneous generation (i.e. abiogenesis) believed that living organisms arise from non-living things or decomposing organic matter; and this hypothesis was invoke even till the late 19th century before it was disproven by series of experiments conducted by notable scientists.

Francesco Redi (1626-1697), an Italian Physicianwas the first to attack the theory of spontaneous generation, and this happened in 1668. At a time when it was widely believed that maggots arose from decaying meat, Redi carried out his experiment by filling a series of jars with decaying meat in order to disprove this belief. Some of the jars was left completely open to the air (the test); others were completely sealed while the remaining jars was covered with fine clothe or gauze (which prevented insects from entering). The flasks or jars that were completely sealed and covered with gauze served as the controls.

Francesco Redi believed that flies deposited eggs on the decaying meat, and this resulted to the development of maggots on the meat. After some days, it was discovered that maggots appeared only in the open jars in which the flies could easily reach and lay their eggs. Maggots did not appear in the jars that where completely sealed or covered with gauze. The laying of eggs on the decaying meat led to the development of maggots on the meat, and this was enough for Redi to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation. Francesco Redi challenged the theory of spontaneous generation by showing in his jar-decaying meat experiment that the maggot that appeared on the decaying meat (in the opened jar) came from the eggs of the fly deposited on the meat, and that the meat did not produce them. Despite Redi’s significant experiment (which gave impetus to the origin of life), the theory of spontaneous generation or abiogenesis remained strong and this continued for many centuries.

John Needham (1713-1781) used the boiling technique to determine whether or not boiling killed microorganisms. Needham supported the theory of spontaneous generation with his mutton or chicken broth boiling flask technique. He boiled mutton broth and put it in a flask which was tightly sealed after the broth was introduced in it. It was believed that boiling kills microorganisms. Needham allowed the flask for a long period of time, and discovered later that microorganisms developed in the broth even after boiling. Though his experiment supported abiogenesis; the fight to disprove spontaneous generation continued.

Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799), an Italian cleric boiled nutrient solutions in flask, and he showed in his experiment (which was a modification of Needham’s) that flask containing broth when sealed and boiled had no microbial growth. He drew out air from the flask before boiling in order to create a partial vacuum in the medium. Lazzaro was not convinced with Needham’s experiment because he contemplated that microorganisms could have entered the broth after it was boiled and before it was sealed. He showed in his significant work that air carried germs or microorganisms to the broth, and that air could support the growth of the organisms in the broth. However, Lazzaro’s experiment was still not accepted by supporters of spontaneous generation who believed that abiogenesis could not occur in the absence of air.

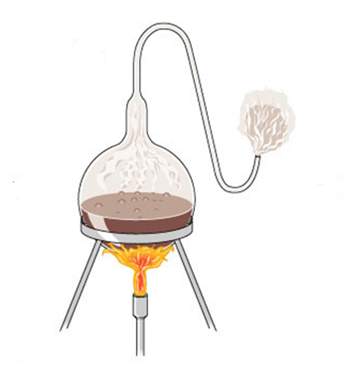

The theory of spontaneous generation was later put to rest and totally disproven by the significant experiments of Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) in 1859 and John Tyndall (1820-1893), an English physicist who extended Pasteur’s work by working on heat-resistant bacteria. A French chemist and microbiologist, Pasteur used the swan-necked flask experiment (Figure 2) to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation. Louis Pasteur improved on the works of Needham and Spallanzani by boiling meat broth in bent-flasks which was opened to the air. Pasteur suggested that microorganisms in the air (which could contaminate the sterile broth) would be trapped on the sides of the bent flasks before they could finally reach the broth; and that if sterile broth had no prior contact with microorganisms, the broth would still remain sterile or free from microbes.

Louis Pasteur boiled meat broth in a flask and heated the neck of the flask in a flame until it became bent or curved (i.e. swan-necked). Though air could easily enter the flask, microorganisms in the air would be trapped in the neck of the bent flask. This was Pasteur’s idea of disproving the theory of spontaneous generation. The curved or bent flasks containing the broth were boiled to kill any form of microorganisms in it; and the flask was observed for a period of time for any possible microbial growth. But if the neck of the bent-flask was broken, dust particles or air-borne microbes would enter the flask and the broth will become polluted, and this will support the growth of germs.

Pasteur’s swan-necked experiment showed that the broth remained sterile for months because air-borne microbes were trapped in the bent-neck of the flask. Louis Pasteur then concluded that life only arises from life, and this is known as biogenesis. Though Louis Pasteur’s work laid the theory of spontaneous generation to rest; his notable experiment also showed that microbes are ubiquitous i.e. they are everywhere (even in the air).

The theory of spontaneous generation was wildly acceptable to many as at the time it was invoke, but the experiments of Louis Pasteur and that of John Tyndall helped in laying it to rest once and for all. John Tyndall (1820-1893) gave impetus to the experiment of Louis Pasteur by showing in 1877 that dust particles indeed harboured microbes, and that the absence of it could cause the broth to remain sterile.

Tyndall went a step further to show the existence of heat-resistant forms of bacteria known as endospores, which are not easily killed by boiling. It is possible that the bacterial growth that was observed in Needham’s experiment after boiling was endopores (i.e. heat-resistant forms of bacteria). The observance of bacterial growth after boiling chicken broth made Needham to propose in 1745 that spontaneous generation did occur because microbes grew after the process. However, Pasteur and Tyndall’s experiment put a final stop to the theory of spontaneous generation and they convincingly showed that abiogenesis did not actually occur.

References

Barrett J.T (1998). Microbiology and Immunology Concepts. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers. USA.

Beck R.W (2000). A chronology of microbiology in historical context. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

Brooks G.F., Butel J.S and Morse S.A (2004). Medical Microbiology, 23rd edition. McGraw Hill Publishers. USA. Pp. 248-260.

Chung K.T, Stevens Jr., S.E and Ferris D.H (1995). A chronology of events and pioneers of microbiology. SIM News, 45(1):3–13.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Slonczewski J.L, Foster J.W and Gillen K.M (2011). Microbiology: An Evolving Science. Second edition. W.W. Norton and Company, Inc, New York, USA.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Wainwright M (2003). An Alternative View of the Early History of Microbiology. Advances in applied microbiology. Advances in Applied Microbiology, 52:333–355.

Willey J.M, Sherwood L.M and Woolverton C.J (2008). Harley and Klein’s Microbiology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, USA.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.