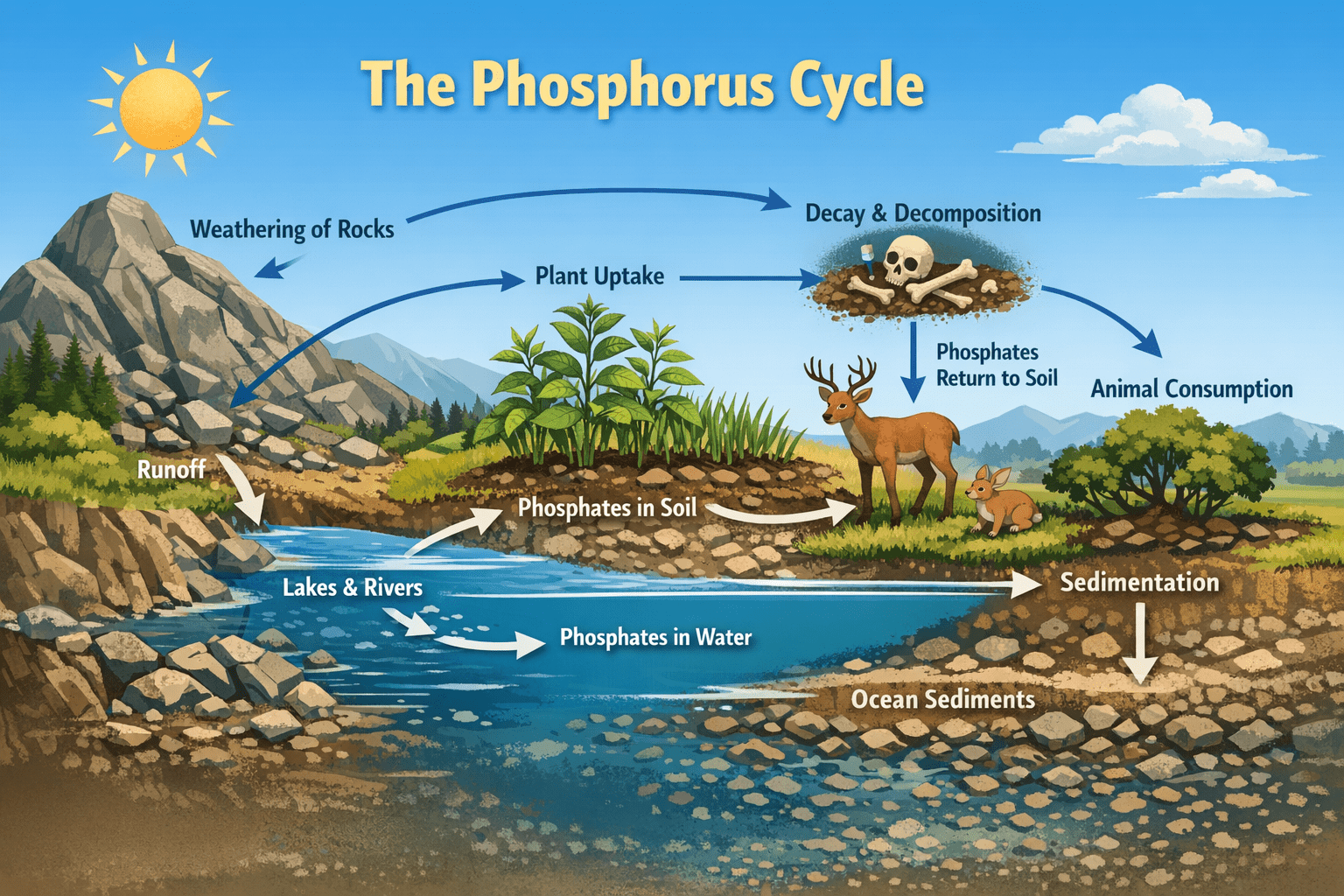

The phosphorus cycle is a fundamental biogeochemical process that governs the movement and transformation of phosphorus among the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere. Unlike other major nutrient cycles such as the carbon or nitrogen cycles, phosphorus lacks a significant gaseous phase, making its circulation through the Earth system comparatively slow and spatially constrained. Despite this limitation, phosphorus plays an indispensable role in biological productivity and ecosystem functioning. It is a core constituent of nucleic acids, phospholipids, and energy-transfer molecules such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and it is therefore essential to the growth, reproduction, and survival of all living organisms.

From a human perspective, the phosphorus cycle is tightly linked to agricultural productivity, food security, and environmental sustainability. Phosphorus availability often limits plant growth in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, prompting extensive human intervention through mining and fertilizer application. However, these interventions have substantially altered natural phosphorus fluxes, contributing to problems such as soil nutrient imbalance, eutrophication of freshwater and marine systems, and the long-term depletion of finite phosphate rock reserves. Understanding the mechanisms, reservoirs, and rates of phosphorus cycling is therefore critical for managing ecosystems sustainably and ensuring future food production.

Chemical Forms and Natural Occurrence of Phosphorus

Phosphorus does not occur freely in nature due to its high reactivity. Instead, it is primarily found as part of phosphate ions, with orthophosphate (PO₄³⁻) being the most abundant and biologically relevant form. These phosphate ions combine with various cations, such as calcium, iron, and aluminum, to form phosphate salts that are widespread in rocks, soils, sediments, and aquatic systems.

The largest natural reservoir of phosphorus is the lithosphere, particularly in sedimentary and igneous rocks. Over geological time scales, phosphate minerals accumulate in ocean sediments and are eventually uplifted through tectonic processes to form terrestrial rock deposits. Smaller but ecologically active pools of phosphorus exist in soils, freshwater bodies, oceans, and living organisms. Although these pools contain only a fraction of total global phosphorus, they are central to ecosystem productivity.

In soils, phosphorus exists in both inorganic and organic forms. Inorganic phosphorus is associated with mineral particles, while organic phosphorus is incorporated into soil organic matter derived from plant and microbial residues. The balance between these forms, and their availability to plants, depends strongly on soil pH, mineral composition, microbial activity, and land management practices.

Major Components of the Phosphorus Cycle

Weathering and Erosion

The phosphorus cycle begins primarily with the weathering of phosphate-containing rocks. Physical and chemical weathering processes, including temperature fluctuations, water action, and the activity of plant roots and microorganisms, gradually break down rocks and release phosphate ions into the soil and surrounding water bodies. This release is typically slow, making weathering the rate-limiting step of the phosphorus cycle.

Once released, phosphates may be retained in soils, absorbed by plants, transported into aquatic systems via runoff, or bound to soil minerals. Erosion accelerates the movement of phosphorus from terrestrial to aquatic environments, particularly in landscapes affected by deforestation, intensive agriculture, or construction activities.

Plant Uptake and Assimilation

Plants absorb phosphorus from the soil primarily in the form of orthophosphate ions dissolved in soil water. Phosphorus is essential for several physiological processes in plants, including energy transfer, photosynthesis, signal transduction, and the synthesis of nucleic acids and membranes. Adequate phosphorus availability promotes root development, flowering, seed formation, and overall crop yield.

However, phosphorus is often present in soils at low concentrations relative to plant demand. Much of the soil phosphorus is chemically bound in forms that are not readily accessible to plants. To overcome this limitation, plants have evolved strategies such as symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi, which enhance phosphorus uptake by increasing the effective root surface area and mobilizing phosphorus from mineral and organic sources.

Transfer Through Food Webs

Phosphorus enters the biological component of ecosystems when plants assimilate phosphate from the soil or water. Herbivorous animals obtain phosphorus by consuming plant tissues, and carnivores acquire it through the consumption of other animals. In this way, phosphorus moves through food chains and food webs, becoming incorporated into the tissues of organisms at successive trophic levels.

Within organisms, phosphorus is a structural and functional element. It forms part of DNA and RNA, enabling genetic information storage and transfer. It is also a key component of ATP, which drives metabolic reactions, and of phospholipids, which constitute cellular membranes. In vertebrates, phosphorus combines with calcium to form calcium phosphate minerals that provide structural strength to bones and teeth.

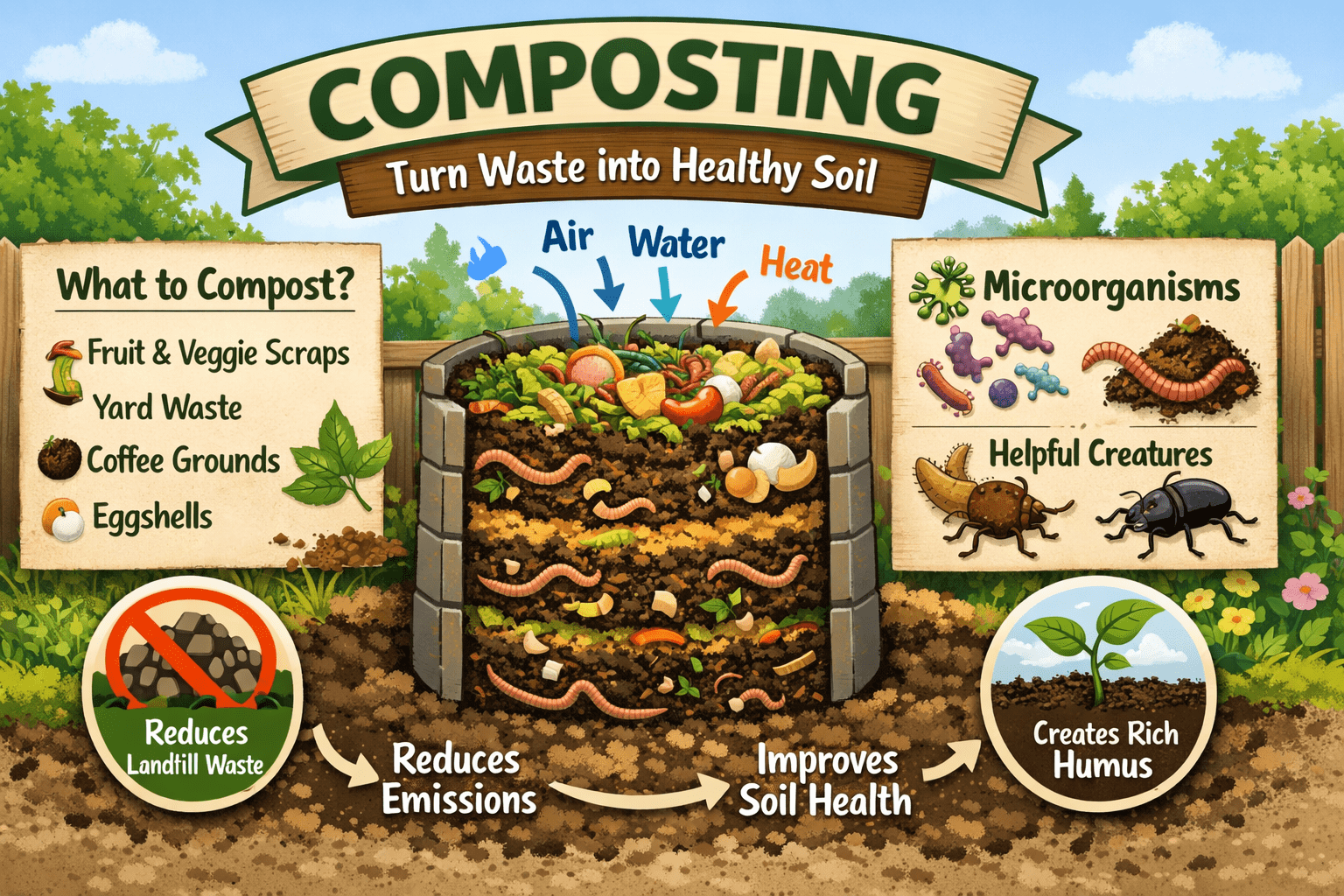

Decomposition and Recycling

The death and decomposition of plants and animals return phosphorus to the soil and aquatic environments. Decomposers, including bacteria and fungi, break down organic matter and mineralize organic phosphorus compounds into inorganic phosphate, making them available once again for uptake by plants and microorganisms. This internal recycling is critical for maintaining phosphorus availability within ecosystems, particularly where external inputs from weathering are minimal.

In soils, a dynamic equilibrium exists between phosphorus immobilization in organic matter and mineral forms, and its release through microbial activity. Environmental factors such as temperature, moisture, and oxygen availability strongly influence decomposition rates and, consequently, phosphorus cycling efficiency.

Aquatic Transport and Sedimentation

Phosphates that are not taken up by terrestrial plants may be transported by surface runoff or leaching into rivers, lakes, and oceans. In aquatic ecosystems, phosphorus supports the growth of algae and aquatic plants, forming the base of aquatic food webs. However, excessive phosphorus inputs can disrupt these systems by stimulating algal blooms that reduce water quality and oxygen availability.

Over time, phosphorus in aquatic systems may settle out of the water column and become incorporated into sediments. In marine environments, phosphate-rich sediments can eventually form new rock deposits. Through geological uplift and renewed weathering, this sedimentary phosphorus may re-enter the terrestrial cycle, completing the long-term phosphorus cycle.

Absence of a Gaseous Phase and Its Implications

A defining characteristic of the phosphorus cycle is the absence of a significant gaseous phase. Unlike carbon, nitrogen, or sulfur, phosphorus does not readily form volatile compounds under normal Earth surface conditions. As a result, the atmosphere plays only a minor role in phosphorus transport, limited mainly to the movement of dust particles containing phosphate minerals.

This lack of an atmospheric component has important ecological implications. Phosphorus cannot be rapidly redistributed across the globe through atmospheric circulation, making local and regional phosphorus availability highly dependent on geological and soil processes. Consequently, many ecosystems experience chronic phosphorus limitation, particularly those developed on highly weathered soils or isolated from fresh mineral inputs.

Ecological Significance of the Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphorus availability is a key determinant of ecosystem productivity. In terrestrial ecosystems, phosphorus often limits plant growth, especially in tropical and subtropical regions where intense weathering has depleted soil phosphorus over time. In freshwater systems, phosphorus is frequently the primary limiting nutrient controlling algal and plant growth.

Balanced phosphorus cycling supports biodiversity, stable food webs, and efficient energy transfer within ecosystems. Conversely, disruptions to the phosphorus cycle can lead to ecological imbalance. Insufficient phosphorus restricts primary production and can reduce ecosystem resilience, while excessive phosphorus can cause eutrophication, biodiversity loss, and degradation of water resources.

Human Influences on the Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphate Mining and Fertilizer Production

Human activities have dramatically altered the natural phosphorus cycle, primarily through the mining of phosphate rock and its conversion into agricultural fertilizers. Phosphate fertilizers have become essential for modern agriculture, enabling high crop yields and supporting a growing global population. However, phosphate rock is a finite, non-renewable resource, and its extraction concentrates phosphorus fluxes that would otherwise occur slowly over geological time scales.

The global trade and application of phosphorus fertilizers redistribute phosphorus across continents, often leading to localized surpluses in agricultural regions and deficits elsewhere. Inefficient fertilizer use results in significant phosphorus losses to waterways, exacerbating environmental problems.

Land-Use Change and Deforestation

Land-use changes, including deforestation, urbanization, and intensive agriculture, influence phosphorus cycling by altering soil structure, erosion rates, and biological activity. Removal of vegetation reduces phosphorus retention in soils and increases runoff and erosion, accelerating the transfer of phosphorus from land to water bodies.

Environmental Consequences

One of the most significant consequences of human-altered phosphorus cycling is eutrophication. Excess phosphorus entering lakes, rivers, and coastal waters promotes excessive algal growth, which can lead to hypoxia, fish kills, and the loss of aquatic biodiversity. These impacts pose serious threats to drinking water supplies, fisheries, and recreational water use.

Toward Sustainable Phosphorus Management

Sustainable management of the phosphorus cycle requires strategies that balance agricultural productivity with environmental protection. These strategies include improving fertilizer efficiency, recycling phosphorus from organic waste streams, adopting conservation agriculture practices, and restoring natural vegetation to reduce erosion and runoff.

Advances in soil testing, precision agriculture, and microbial biotechnology offer opportunities to enhance phosphorus use efficiency and reduce losses. At the policy level, integrated nutrient management and international cooperation are needed to address the global challenges associated with phosphorus scarcity and pollution.

The phosphorus cycle is a slow but vital biogeochemical process that underpins life on Earth. Its unique characteristics, particularly the absence of a gaseous phase and the dominance of geological reservoirs, make phosphorus both essential and vulnerable to mismanagement. While natural processes recycle phosphorus over long time scales, human activities have profoundly accelerated and redirected its movement, creating both benefits and environmental risks.

A thorough understanding of the phosphorus cycle is essential for developing sustainable solutions that ensure long-term ecosystem health and food security. By aligning agricultural practices, environmental stewardship, and resource management, it is possible to maintain the integrity of the phosphorus cycle while meeting the needs of a growing global population.

References

Abrahams P.W (2006). Soil, geography and human disease: a critical review of the importance of medical cartography. Progress in Physical Geography, 30:490-512.

Ahring B.K, Angelidaki I and Johansen K (1992). Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci. Technol, 30, 241–249.

Andersson L and Rydberg L (1988). Trends in nutrient and oxygen conditions within the Kattegat: effects on local nutrient supply. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci, 26:559–579.

Ballantyne A.P, Alden C.B, Miller J.B, Tans P.P and White J.W.C (2012). Increase in observed net carbon dioxide uptake by land and oceans during the past 50 years. Nature, 488: 70-72.

Baumgardner D.J (2012). Soil-related bacterial and fungal infections. J Am Board Fam Med, 25:734-744.

Bennett E.M, Carpenter S.R and Caraco N.F (2001). Human impact on erodable phosphorus and eutrophication: a global perspective. BioScience, 51:227–234.

Bunting B.T. and Lundberg J (1995). The humus profile-concept, class and reality. Geoderma, 40:17–36.

Roberto P. Anitori (2012). Extremophiles: Microbiology and Biotechnology. First edition. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, England.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Sawyer C.N, McCarty P.L and Parkin G.F (2003). Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishers, New York, USA.

Ulrich A and Becker R (2006). Soil parent material is a key determinant of the bacterial community structure in arable soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 56(3):430–443.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.