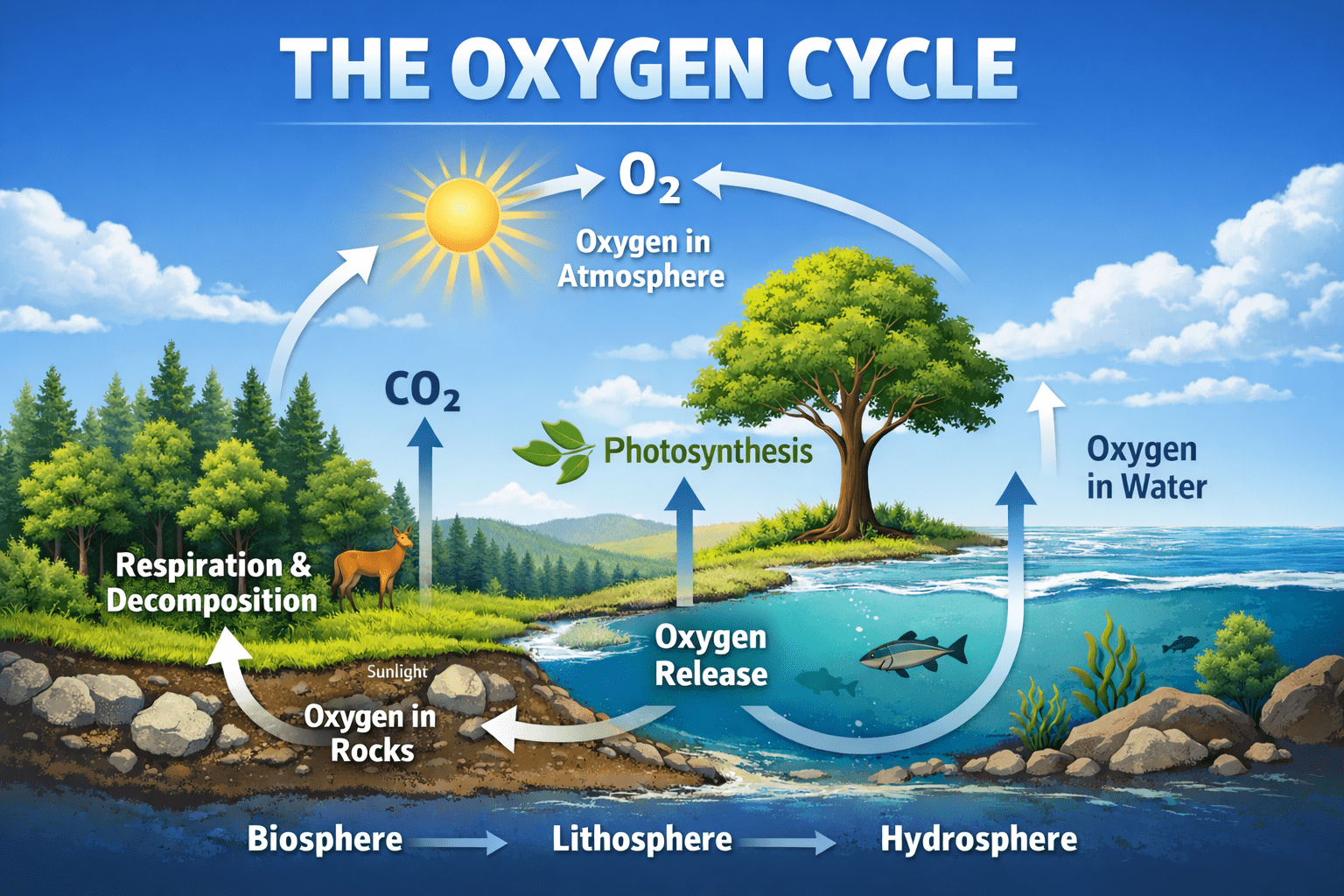

The oxygen cycle is one of the most fundamental biogeochemical cycles on Earth, underpinning the survival and evolution of nearly all complex life forms. It describes the continuous movement of oxygen among the atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, and hydrosphere through a series of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Oxygen is not only a major component of the Earth’s atmosphere but also a critical element in cellular respiration, energy transfer, ecosystem productivity, and climate regulation. Without a functioning oxygen cycle, aerobic life as it exists today would be impossible.

At its core, the oxygen cycle is driven by the complementary biological processes of photosynthesis and respiration. Photosynthesis, primarily carried out by green plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, releases oxygen into the atmosphere as a by-product of converting carbon dioxide and water into organic compounds using solar energy. Respiration, decomposition, and combustion consume oxygen and return carbon dioxide and water to the environment. These tightly linked processes ensure that oxygen is continuously recycled rather than depleted.

Understanding the oxygen cycle is increasingly important in the context of global environmental change. Human activities such as deforestation, fossil fuel combustion, industrial pollution, and climate change have the potential to disrupt oxygen-producing and oxygen-consuming processes.

Definition and Overview of the Oxygen Cycle

The oxygen cycle can be defined as the biogeochemical cycle through which oxygen is exchanged among the major reservoirs of the Earth system: the atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, and hydrosphere. In the atmosphere, oxygen exists primarily as molecular oxygen (O₂), which constitutes approximately 21 percent of the air, making it the second most abundant uncombined element after nitrogen. Oxygen also occurs in trace forms such as ozone (O₃), which plays a crucial protective role in the upper atmosphere.

In the biosphere, oxygen is an essential component of living organisms. It is incorporated into water, carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, and it is indispensable for aerobic respiration. In the lithosphere, oxygen is a major constituent of minerals and rocks, often combined with elements such as silicon, iron, aluminum, and calcium in the form of oxides and silicates. In the hydrosphere, oxygen is present both as dissolved molecular oxygen and as a component of water molecules (H₂O).

The oxygen cycle involves the continuous transformation of oxygen between these reservoirs. While large quantities of oxygen are locked in rocks and minerals for geological timescales, the biologically active portion of the cycle – especially the exchange between the atmosphere, biosphere, and hydrosphere operates on much shorter timescales and directly supports life processes.

Photosynthesis: The Primary Driver of the Oxygen Cycle

Photosynthesis is the fundamental biological process that drives the oxygen cycle. It is carried out by autotrophic organisms, including terrestrial green plants, aquatic algae, and photosynthetic bacteria such as cyanobacteria. During photosynthesis, light energy from the sun is captured by chlorophyll and other pigments and used to convert carbon dioxide (CO₂) and water (H₂O) into glucose and other carbohydrates. Oxygen is released as a by-product of the splitting of water molecules during the light-dependent reactions.

The simplified chemical equation for photosynthesis is:

6CO₂ + 6H₂O + light energy → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂

This process is the primary source of free oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere. Before the evolution of photosynthetic organisms, atmospheric oxygen levels were extremely low. The emergence of oxygenic photosynthesis, particularly by cyanobacteria during the Great Oxidation Event approximately 2.4 billion years ago, fundamentally transformed the Earth’s atmosphere and enabled the evolution of aerobic life.

Photosynthesis not only replenishes atmospheric oxygen but also forms the base of most food webs. The organic compounds produced serve as energy sources for heterotrophic organisms, which in turn consume oxygen during respiration. In this way, photosynthesis links the oxygen cycle directly to the carbon cycle and the flow of energy through ecosystems.

Respiration and Decomposition: Oxygen Consumption Processes

Respiration is the primary biological process through which oxygen is consumed. All aerobic organisms—including animals, plants, fungi, and many microorganisms use oxygen to break down organic molecules and release energy needed for growth, maintenance, and reproduction. During cellular respiration, glucose and other organic substrates are oxidized in the presence of oxygen, producing carbon dioxide, water, and energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

The simplified equation for aerobic respiration is:

C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂ → 6CO₂ + 6H₂O + energy

Although plants are major producers of oxygen, they also consume oxygen through respiration, particularly at night when photosynthesis ceases. Thus, the net contribution of plants to atmospheric oxygen depends on the balance between photosynthesis and respiration.

Decomposition is another critical oxygen-consuming process. When plants and animals die, their organic matter is broken down by decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi. In aerobic environments, these microorganisms use oxygen to decompose organic waste materials into simpler inorganic substances such as carbon dioxide, water, nitrates, and phosphates. This process not only consumes oxygen but also recycles nutrients back into ecosystems, supporting new plant growth and sustaining the oxygen cycle.

Oxygen in the Atmosphere and the Role of Ozone

Atmospheric oxygen plays multiple roles beyond respiration. Molecular oxygen (O₂) is relatively stable, but under certain conditions it can be transformed into ozone (O₃), a molecule consisting of three oxygen atoms. Ozone is formed in the stratosphere when ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun splits molecular oxygen into individual oxygen atoms, which then combine with O₂ to form O₃.

The ozone layer is critically important for life on Earth because it absorbs and filters out most of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. Without this protective shield, high levels of UV radiation would reach the Earth’s surface, increasing the risk of skin cancer, genetic mutations, and damage to plants and aquatic ecosystems. In this way, oxygen indirectly supports life by regulating the quality and intensity of solar radiation reaching the planet.

At the same time, ozone in the lower atmosphere (the troposphere) can be harmful, acting as a pollutant that damages lung tissue, reduces crop yields, and contributes to smog formation. This dual role highlights the complex and context-dependent nature of oxygen-related compounds in the environment.

Oxygen in the Hydrosphere and Aquatic Ecosystems

Oxygen is a vital component of aquatic ecosystems, where it exists as dissolved oxygen (DO) in water. Aquatic plants, algae, and phytoplankton produce oxygen through photosynthesis, while aquatic animals and microorganisms consume it through respiration. The concentration of dissolved oxygen is a key indicator of water quality and ecosystem health.

Well-oxygenated waters support diverse and productive aquatic communities. In contrast, low oxygen conditions, known as hypoxia, can lead to fish kills, loss of biodiversity, and the disruption of ecological processes. Hypoxia often results from excessive nutrient inputs, such as nitrogen and phosphorus from agricultural runoff and wastewater, which stimulate algal blooms. When these algae die and decompose, large amounts of oxygen are consumed, depleting dissolved oxygen levels.

Oxygen in water is also involved in important chemical reactions, including the oxidation of metals and the breakdown of pollutants. Thus, the oxygen cycle in the hydrosphere is closely linked to water quality, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem sustainability.

Oxygen in the Lithosphere and Geological Processes

In the lithosphere, oxygen is primarily stored in chemically bound forms within minerals and rocks. It is a major constituent of silicate minerals, which make up the bulk of the Earth’s crust, as well as oxides such as iron oxide. Although this reservoir is not directly involved in short-term biological cycling, geological processes such as weathering, erosion, and volcanic activity influence the long-term oxygen balance.

Chemical weathering of rocks often involves oxidation reactions in which oxygen reacts with minerals, gradually altering their composition. For example, the oxidation of iron-bearing minerals leads to the formation of rust-colored iron oxides. These processes consume atmospheric oxygen over geological timescales.

Conversely, tectonic activity and volcanic eruptions can release gases that indirectly affect atmospheric oxygen levels by influencing climate and biological productivity. Over millions of years, the interaction between biological oxygen production and geological oxygen consumption has shaped the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere.

Interactions Between the Oxygen Cycle and Other Biogeochemical Cycles

The oxygen cycle does not operate in isolation; it is tightly interconnected with other major biogeochemical cycles, particularly the carbon, nitrogen, and water cycles. The exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and respiration directly links the oxygen cycle to the carbon cycle. Any factor that alters carbon storage or release, such as deforestation or fossil fuel combustion, also affects oxygen dynamics.

The nitrogen cycle also interacts with oxygen availability. Many nitrogen transformations, such as nitrification, require oxygen, while others, such as denitrification, occur under low-oxygen conditions. Changes in oxygen levels can therefore influence soil fertility, water quality, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Similarly, the water cycle affects oxygen distribution through processes such as precipitation, runoff, and evaporation, which influence the availability of oxygen in soils and aquatic systems. Understanding these interactions is essential for managing ecosystems and predicting environmental responses to change.

Importance of the Oxygen Cycle to Life and Ecosystem Functioning

Oxygen is indispensable to most forms of life. Aerobic respiration yields significantly more energy than anaerobic processes, enabling the development of complex, energy-demanding organisms, including humans. Oxygen is also essential for numerous biochemical reactions, including the synthesis of energy-rich molecules and the detoxification of harmful substances.

Beyond individual organisms, the oxygen cycle supports ecosystem-level processes such as productivity, nutrient recycling, and waste decomposition. Aerobic microorganisms play a crucial role in breaking down organic matter, preventing the accumulation of waste and releasing nutrients that support plant growth. In this sense, oxygen availability underpins the stability and resilience of ecosystems.

The role of oxygen in climate regulation, through its involvement in ozone formation and greenhouse gas interactions, further underscores its global significance. A stable oxygen cycle contributes to a habitable climate and protects life from harmful radiation.

Human Impacts on the Oxygen Cycle

Human activities have increasingly influenced the oxygen cycle, both directly and indirectly. Deforestation and land-use change reduce the capacity of terrestrial ecosystems to produce oxygen through photosynthesis. Although the global atmospheric oxygen pool is large, localized and long-term reductions in vegetation can disrupt regional oxygen and carbon balances.

The combustion of fossil fuels consumes oxygen and releases carbon dioxide and other pollutants into the atmosphere. While this does not significantly reduce global oxygen levels in the short term, it contributes to climate change, ocean acidification, and air pollution, all of which affect oxygen dynamics in ecosystems.

In aquatic systems, nutrient pollution from agriculture, industry, and urban areas has led to widespread hypoxia and the formation of so-called “dead zones” in coastal waters. These conditions severely disrupt the oxygen cycle in the hydrosphere and threaten fisheries and biodiversity.

Strategies for Sustaining the Oxygen Cycle

Maintaining a healthy oxygen cycle requires integrated environmental management and sustainable practices. Protecting and restoring forests, wetlands, and grasslands enhances photosynthetic oxygen production and supports biodiversity. Sustainable agriculture practices, including reduced fertilizer use and improved nutrient management, can prevent oxygen depletion in aquatic ecosystems.

Reducing fossil fuel consumption and transitioning to renewable energy sources can mitigate climate change and its indirect effects on oxygen cycling. Pollution control measures that limit the release of nutrients and contaminants into water bodies are also essential for preserving dissolved oxygen levels.

Public awareness and environmental education play a critical role in promoting behaviors and policies that protect the oxygen cycle. By recognizing the oxygen cycle as a shared global resource, societies can take informed actions to ensure its long-term stability.

The oxygen cycle is a dynamic and indispensable component of the Earth system, sustaining life, regulating climate, and maintaining ecosystem health. Driven primarily by photosynthesis and balanced by respiration, decomposition, and geological processes, the cycle ensures the continuous availability of oxygen across the planet’s spheres. Its close integration with other biogeochemical cycles highlights the complexity and interconnectedness of natural systems.

As human activities increasingly alter the environment, understanding and sustaining the oxygen cycle has become a critical scientific and societal challenge. Through responsible resource management, pollution reduction, and ecosystem conservation, it is possible to protect the processes that maintain Earth’s oxygen balance. Safeguarding the oxygen cycle is ultimately essential for preserving life on Earth and ensuring a sustainable future for generations to come.

References

Abrahams P.W (2006). Soil, geography and human disease: a critical review of the importance of medical cartography. Progress in Physical Geography, 30:490-512.

Ahring B.K, Angelidaki I and Johansen K (1992). Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci. Technol, 30, 241–249.

Andersson L and Rydberg L (1988). Trends in nutrient and oxygen conditions within the Kattegat: effects on local nutrient supply. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci, 26:559–579.

Ballantyne A.P, Alden C.B, Miller J.B, Tans P.P and White J.W.C (2012). Increase in observed net carbon dioxide uptake by land and oceans during the past 50 years. Nature, 488: 70-72.

Baumgardner D.J (2012). Soil-related bacterial and fungal infections. J Am Board Fam Med, 25:734-744.

Paul E.A (2007). Soil Microbiology, ecology and biochemistry. 3rd edition. Oxford: Elsevier Publications, New York.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Pelczar M.J., Chan E.C.S. and Krieg N.R. (2003). Microbiology of Soil. Microbiology, 5th Edition. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, New Delhi, India.

Pepper I.L and Gerba C.P (2005). Environmental Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. Second Edition. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, USA.

Roberto P. Anitori (2012). Extremophiles: Microbiology and Biotechnology. First edition. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, England.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Sawyer C.N, McCarty P.L and Parkin G.F (2003). Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishers, New York, USA.

Ulrich A and Becker R (2006). Soil parent material is a key determinant of the bacterial community structure in arable soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 56(3):430–443.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.