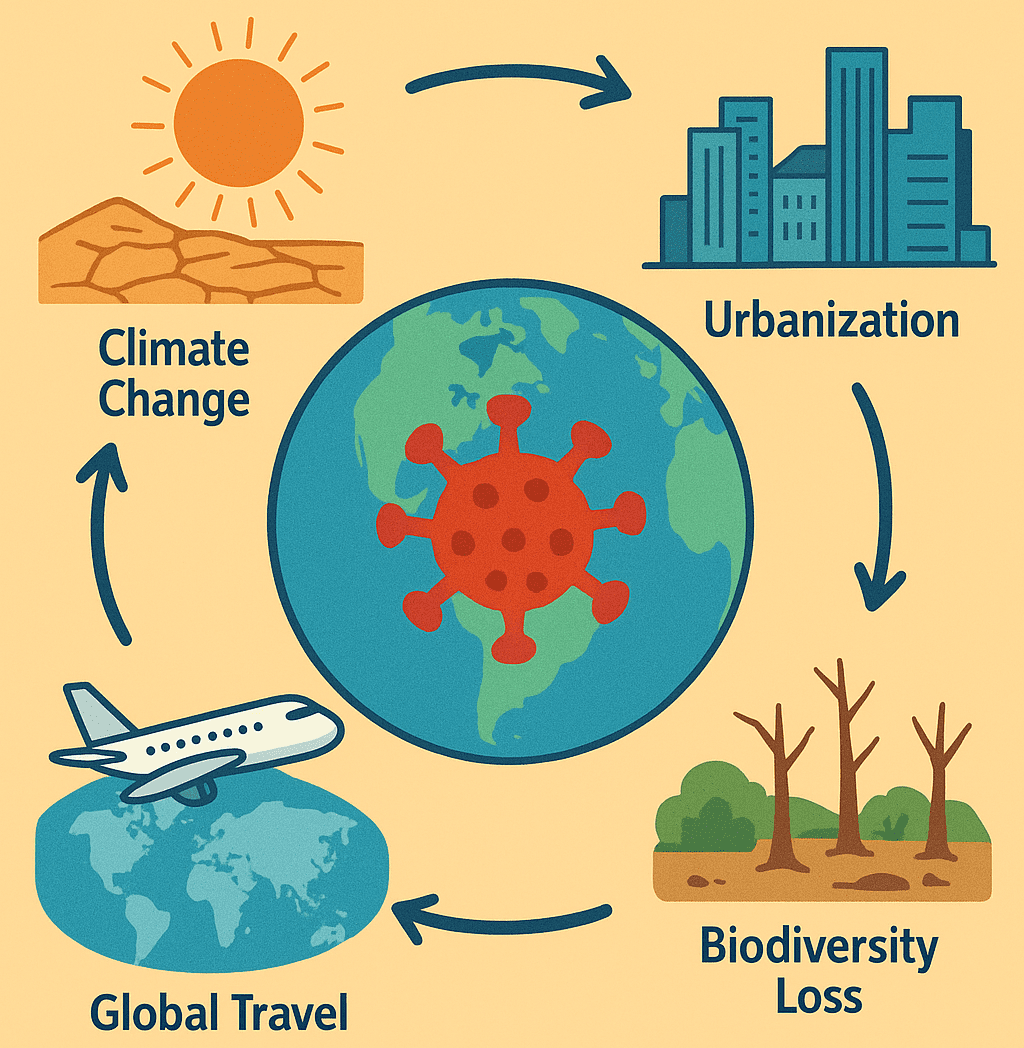

The dynamics of infectious disease transmission are shaped by a complex interplay of environmental, biological, social, and climatic factors. Over the past decades, a growing body of evidence has highlighted the significant role global change plays in accelerating the emergence, re-emergence, and geographic spread of infectious diseases. Global change refers to the variety of changes unfolding across our planet earth. This also includes alterations to climate, land, water, and ecosystems, largely driven by human activities. It encompasses both natural and anthropogenic components, with significant impacts stemming from human population growth, energy use, land use changes, and pollution. These changes are interconnected and have profound implications for ecological systems and human societies. Global change encompasses a broad spectrum of human-driven processes, including climate change, deforestation, urbanization, biodiversity loss, global travel and trade, agricultural intensification, pollution, and socioeconomic disparities. These changes are interconnected and often act synergistically to reshape ecosystems and human-pathogen interactions.

Climate Change and Disease Dynamics

Climate change is a long-term change in the average weather patterns that have come to define earth’s local, regional and global climates. These changes have a broad range of observed effects that are synonymous with the term. While global warming refers to the rise in earth’s average temperatures, climate change on the other hand encompasses the broader shifts in weather patterns and ecosystems caused by this warming.

Global warming is the long-term heating of the earth’s surface observed since the pre-industrial period (between 1850 and 1900) due to human activities, primarily fossil fuel burning, which increases heat-trapping greenhouse gas levels in the earth’s atmosphere.

Since the pre-industrial period, human activities including globalization, industrialization, intensive farming etc. are estimated to have increased the earth’s global average temperature by about 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), a number that is currently increasing by more than 0.2 degrees Celsius (0.36 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade. The current warming trend is unequivocally the result of human activity since the 1950s and is proceeding at an unprecedented rate over millennia.

Climate change is one of the most significant and well-documented environmental drivers of infectious disease emergence and spread globally. Through shifts in temperature, humidity, precipitation patterns, sea level rise, and the frequency of extreme weather events, climate change alters the ecology of pathogens, hosts, and vectors – ultimately shaping where, when, and how infectious diseases occur. Climate change affect our health, ability to grow food, housing, safety and work.

Vector-Borne Diseases

Vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, dengue fever, Zika virus, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Lyme disease, are among the most climate-sensitive diseases. Vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks, and sandflies are cold-blooded, meaning their internal temperature and therefore their life cycle and behavior is influenced by ambient temperatures. Warmer temperatures can increase vector population sizes, speed up the maturation of larvae, enhance feeding frequency, and shorten the incubation period of pathogens within the vector. This combination accelerates the transmission cycle of the infectious diseases carried by these vectors.

For example, the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which transmits dengue, thrives in warm, urban environments and has expanded into new regions as temperatures rise. Similarly, Anopheles mosquitoes, which spread malaria, are increasingly found at higher altitudes and latitudes where they were previously unable to survive. Warmer conditions have also contributed to the rise in Lyme disease cases, with ticks like Ixodes scapularis expanding into previously unsuitable environments in Canada, the northeastern U.S., and parts of Europe like Germany and France.

Geographical Expansion of Disease Zones

Climate-induced habitat shifts mean that many disease-carrying vectors are now moving into regions that historically had little or no exposure to certain infectious diseases. This has significant implications for public health, especially in populations that lack immunity or adequate healthcare systems to manage newly emerging threats. In East Africa and the Andes Mountains, for instance, malaria-carrying mosquitoes have been reported at higher elevations where cooler temperatures previously limited their survival. In Europe and North America, warmer winters have allowed ticks and the pathogens they carry to survive and reproduce over longer periods, increasing the incidence of Lyme disease.

Waterborne and Foodborne Diseases

Changes in rainfall and extreme weather events also contribute to outbreaks of waterborne and foodborne diseases. Heavy rainfall and flooding can overwhelm sewage systems and contaminate drinking water sources, leading to outbreaks of diseases like cholera, cryptosporidiosis, hepatitis A, and typhoid fever. Warmer water temperatures can also increase the growth of harmful algal blooms and pathogens like Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera.

Climate change intensifies the risks and challenges associated with infectious diseases by reshaping environmental conditions in favor of disease vectors and pathogens. Without coordinated mitigation and adaptation strategies, these effects are likely to worsen, particularly in vulnerable communities.

Land Use Change and Deforestation

Human-driven changes to land use such as deforestation, agricultural expansion, mining, and infrastructure development are among the most significant contributors to the emergence and spread of infectious diseases globally. These activities drastically alter ecosystems, reducing natural habitats, cause biodiversity loss and constantly bring humans into closer contact with wildlife and their associated pathogens.

Zoonotic Spillover and Ecosystem Disruption

Over 60% of emerging infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, meaning they originate in animals before spilling over into the human population. Land use change accelerates this process by dismantling natural barriers that once separated wildlife from humans and domestic animals. As forests are cleared for farming or settlements, animals such as bats, primates, and rodents (which are known to be natural reservoirs of various viruses) – are displaced or stressed. In their search for food and shelter, these animals venture closer to human dwellings, increasing the chance of disease transmission.

A well-documented example is the 1998 Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia, which was directly linked to deforestation and the expansion of pig farms into previously forested areas. Fruit bats, the natural hosts of Nipah virus, lost their habitat and began feeding on fruit trees planted near pig farms. The bats transmitted the virus to pigs, which then infected humans working on the farms. The outbreak resulted in over 100 human deaths and devastated Malaysia’s pig farming industry.

Another example is Lassa fever which is endemic in West African countries and other places. Lassa fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic illness caused by the Lassa virus, primarily found in West Africa. It is a zoonotic disease, meaning it is naturally transmitted from animals to humans. The primary reservoir of the virus is the multimammate rat (Mastomys natalensis), which sheds the virus in its urine and feces. Human infection often occurs through direct contact with these rodent excretions, contaminated food, or, in rare cases, person-to-person transmission. Changes in land use, such as deforestation, agricultural expansion, and urbanization, can increase human-rodent contact, thereby driving the risk of Lassa virus spillover into human populations.

What are zoonotic diseases?

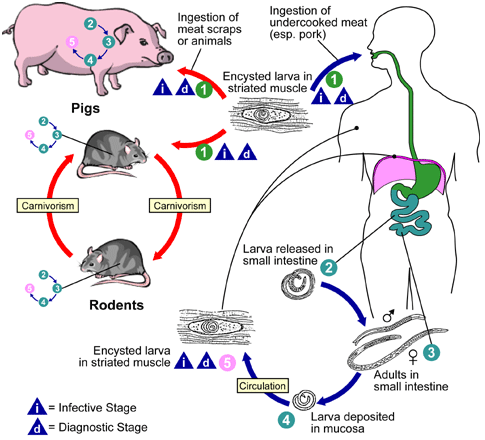

Zoonotic diseases, also known as zoonoses, are infectious diseases caused by pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi that can be transmitted from animals to humans, posing significant public health risks worldwide. These diseases can spread through direct contact with the saliva, blood, urine, feces, or other body fluids of an infected animal, as well as through indirect contact with environments contaminated by pathogens, including animal habitats, pet food, or surfaces that have been in contact with infected animals. Examples of zoonotic diseases include rabies, a viral disease primarily transmitted through bites from infected dogs; Ebola virus disease, a severe illness often transmitted from bats or primates to humans; salmonellosis, a bacterial infection commonly spread through contaminated food or contact with infected animals, particularly reptiles and poultry; and COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 – severe acute respiratory coronavirus strain 2) believed to have originated from bats and transmitted to humans through an intermediate host.

Zoonotic diseases represent a major public health concern globally, accounting for a significant percentage of newly identified infectious diseases, with more than 60% of known infectious diseases in humans being zoonotic and approximately 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases derived from animals. The close relationship between humans and animals in agriculture, as pets, and in natural environments further increases the risk of transmission. Preventing zoonotic diseases involves promoting awareness about zoonoses and safe practices when handling animals, encouraging hygiene practices such as handwashing and proper food handling, implementing safe and appropriate guidelines for animal care in agricultural settings to minimize outbreaks, and monitoring and tracking disease outbreaks to implement control measures. By understanding zoonotic diseases and their transmission, individuals and communities can take proactive steps to reduce the risk of infection and protect public health.

Edge Effects and Human Encroachment

When large, continuous forests are broken into smaller patches by roads, farms, or settlements, “edge effects” occur. These edges, where human-altered landscapes meet remaining fragments of forest, become high-risk zones for pathogen spillover. Wildlife density may increase near edges as animals are forced into smaller territories, and interactions between wildlife, humans, and domestic animals intensify.

Edge habitats also often attract generalist species like rodents and mosquitoes -competent hosts for many diseases – which can flourish in disturbed ecosystems. This shift in wildlife community composition makes it easier for pathogens to jump species, adapt to new hosts, and eventually spread to humans. For instance, fragmented forests in Central and South America have been associated with increased cases of leishmaniasis, as the sand fly vector and rodent hosts thrive in deforested areas.

Moreover, land-use changes often coincide with poor sanitation and healthcare infrastructure, compounding the risk. Displaced wildlife, stressed animal populations, and closer proximity between species all create a perfect storm for novel pathogens to evolve and spread. In essence, by reshaping the landscape, humans are also reshaping the geography of disease.

Urbanization and Population Density

Rapid urbanization, especially in low- and middle-income countries, is transforming landscapes and human settlements at an unprecedented pace. While cities offer economic opportunities and access to services, the speed and scale of urban growth often outpace the development of essential infrastructure. This leads to overcrowded neighborhoods, inadequate housing, poor sanitation, limited access to clean water, and strained healthcare systems – all of which contribute to the spread of infectious diseases.

High population density facilitates close contact among individuals, increasing the potential for person-to-person transmission of respiratory infections like tuberculosis and airborne viruses such as COVID-19. The situation is exacerbated in slums and informal settlements, where up to a billion people globally live under precarious conditions. These areas often lack sewage systems, waste disposal services, and piped water, making them breeding grounds for pathogens and increasing vulnerability to outbreaks like cholera, typhoid, and leptospirosis.

Moreover, urban environments can intensify the transmission of vector-borne diseases. Urban heat islands where concrete and asphalt absorb and radiate heat can elevate temperatures, enhancing mosquito breeding and the replication of viruses such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika. Without adequate public health infrastructure and disease surveillance, these settings can become persistent hotspots for both endemic and emerging infectious diseases.

Global Travel and Trade

In today’s highly interconnected world, the movement of people, animals, and goods across countries and continents has significantly accelerated the global spread of infectious diseases. Rapid travel means that a pathogen can cross borders in mere hours, challenging traditional containment methods and local health infrastructures.

Pandemic Spread: International air travel has played a major role in the global dissemination of recent pandemics. The 2003 SARS outbreak, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the more recent COVID-19 pandemic all illustrate how quickly infections can spread from one country to another. In many cases, individuals carrying the pathogen were asymptomatic during travel, allowing diseases to establish footholds in distant regions before detection. Urban hubs with high human traffic become hotspots for transmission, further complicating efforts to contain outbreaks.

Invasive Species and Vectors: Global trade can also introduce non-native species that act as vectors or reservoirs for infectious diseases. A notable example is the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), a known vector for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. It has spread to Europe, the Americas, and Africa through the international used tire and ornamental plant trades. These mosquitoes thrive in new environments, especially urbanized areas, increasing the risk of vector-borne disease outbreaks in previously unaffected regions.

Agricultural Intensification and Livestock Production

The global push to meet rising food demands has driven the intensification of agriculture and livestock production, significantly altering human-environment interactions. While industrial-scale farming has improved food availability and economic output, it also fosters the conditions for the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases.

High-Density Animal Farming: Industrial farms often house thousands of animals like chickens, pigs, or cattle in confined spaces. This dense population facilitates the rapid spread of pathogens. Animals under chronic stress and poor hygiene are more susceptible to infections, allowing viruses and bacteria to multiply, mutate, and potentially jump species barriers. Influenza strains such as H1N1 and H5N1 have been linked to intensive poultry and swine operations, where viruses mix and reassort, giving rise to novel, potentially pandemic strains.

Antibiotic Resistance: To prevent disease outbreaks and promote growth, antibiotics are routinely administered to livestock. This overuse has accelerated the development of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria in farm environments. These resistant pathogens can reach humans through multiple pathways: direct contact with animals, consumption of undercooked meat or contaminated water, and through manure used as fertilizer in agricultural fields. The rise of AMR infections, now a major global health concern, is closely tied to intensive agricultural practices, making it a key aspect of the link between global change and disease dynamics.

Pollution and Environmental Degradation

Environmental pollution including contamination of air, water, and soil plays a significant role in influencing the spread of infectious diseases by weakening human immune defenses, altering pathogen survival, and facilitating transmission pathways.

Air Pollution: Airborne pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and ozone (O3) have been linked to increased incidence and severity of respiratory illnesses, including asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia. Exposure to these pollutants compromises the respiratory tract’s natural defenses, making individuals more susceptible to infections caused by pathogenic viruses and bacteria. Air pollution may also enhance the transmission of airborne pathogens in human population. Fine particulate matter can act as carriers or “vehicles” for pathogenic viruses and bacteria, allowing them to remain suspended longer in the air and travel farther distances. This increases the risk of airborne disease spread, especially in densely populated urban areas with poor air quality.

Water Pollution: Contaminated water sources serve as reservoirs and transmission routes for many infectious disease agents. Pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae (that causes cholera), norovirus (implicated in gastroenteritis), Escherichia coli (implicated in foodborne and other gastroenteric diseases), and various protozoans thrive in polluted water environments. Industrial runoff, untreated sewage discharge, and agricultural pesticides and fertilizers contribute to water pollution, creating favorable conditions for these pathogens. Flooding and poor sanitation infrastructure can exacerbate outbreaks by spreading pathogens over large areas. In many low- and middle-income countries, lack of access to clean water and sanitation facilities significantly increases vulnerability to waterborne diseases, leading to recurrent outbreaks of diarrheal diseases, which remain a major cause of mortality worldwide.

Soil pollution with heavy metals and chemicals can also alter microbial communities and facilitate the persistence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, further complicating disease control efforts.

Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Disease Spread

Biodiversity is the variety of life in an ecosystem. It plays a crucial role in regulating disease transmission. When ecosystems lose biodiversity, either due to deforestation, climate change, pollution, or human development, the balance of species changes in a way that often promotes the spread of disease. Biodiversity lossleads to the elimination of poor pathogen hosts while increasing pathogen hosts that are even more susceptible to disease spread.

Mechanisms of Disease Regulation Through Biodiversity: In a healthy, biodiverse ecosystem:

- Many species serve as “poor hosts” for pathogens. These species either do not become infected easily or do not efficiently transmit pathogens. This is good because pathogens will have limited hosts for their transmission in human or animal population, thereby saving everyone from likely infectious disease emergence and spread.

- The presence of these poor hosts creates a “dilution effect,” whereby pathogens are less likely to encounter a suitable host. This reduces the overall transmission rate.

In a disturbed or simplified ecosystem:

- Poor host species often disappear due to environmental pressures or human activities as earlier mentioned.

- The remaining species are frequently “competent hosts” that are better at harboring and transmitting pathogens.

- This shift in community composition facilitates increased pathogen transmission to other animals and humans, thereby increasing the rate of morbidity and possibly mortality in extreme cases.

A Case Study of Rodents and Hantaviruses to explain biodiversity loss and/or refulation

Rodents are one of the most adaptable and fast-reproducing mammals. In environments degraded by human activity (e.g., farms, cities, logging areas), rodent populations often surge because they face fewer predators and competition.

Rodents are also competent hosts for hantaviruses, which are shed in their urine and feces. When humans come into contact with contaminated materials, especially in areas with poor sanitation or ventilation, they can contract hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, a potentially fatal disease.

In intact ecosystems with a diverse array of predators (e.g., foxes, owls, snakes) and competing species, rodent numbers are naturally regulated, and their disease transmission potential is reduced. Biodiversity, therefore, acts as a buffer against potential disease outbreaks.

Other examples:

- Lyme Disease: In North America, biodiversity loss in forests has reduced the number of low-competence hosts like opossums (which kill ticks), while increasing the number of high-competence hosts like white-footed mice, leading to greater Lyme disease risk.

- West Nile Virus: Areas with fewer bird species have shown higher transmission rates of West Nile virus, as the surviving bird species are often more competent hosts for the virus.

The loss of biodiversity not only undermines the resilience of ecosystems but also removes critical checks on the spread of infectious diseases. Protecting diverse ecosystems is a public health strategy as much as it is an environmental imperative.

Socioeconomic Inequality and Vulnerability

Global change does not affect all populations equally. Vulnerability to infectious diseases is often magnified by socioeconomic inequalities, particularly in low-income communities and developing nations. These populations face multiple overlapping challenges that exacerbate their risk of infection, hinder disease prevention efforts, and reduce access to effective treatment and care.

Health Disparities:

One of the fundamental drivers of increased disease vulnerability is inequitable access to essential health services and infrastructure. Many marginalized communities lack consistent access to clean water and sanitation, which are critical for preventing waterborne diseases such as cholera and dysentery. Limited availability of vaccines, diagnostic tools, and effective medicines means that outbreaks in these regions can spread more rapidly and with higher fatality rates.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, resource-poor settings faced delays in vaccine delivery and had inadequate healthcare capacity, leading to disproportionate impacts compared to wealthier countries like the United States of America. More so, inadequate nutrition and chronic stress associated with poverty can weaken immune systems, making individuals more susceptible to infections and less able to recover quickly. Overcrowded living conditions, common in informal settlements or slums, further increase transmission risks for airborne and vector-borne diseases.

Migration and Displacement:

Global change, especially climate change, is a major driver of forced displacement. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events such as floods and droughts, and deteriorating agricultural productivity lead to large-scale migration both within and across national borders. Displaced populations often end up in refugee camps or informal settlements with poor sanitation, limited healthcare, and inadequate shelter, creating hotspots for disease outbreaks. Examples include cholera outbreaks in refugee camps and respiratory infections exacerbated by overcrowding.

Conflict and economic instability linked to environmental pressures also disrupt healthcare systems, making disease surveillance and control efforts difficult. The cumulative effect is that displaced and impoverished populations bear the brunt of infectious disease burdens, highlighting the need for integrated responses that address both environmental and social determinants of health.

The spread of infectious diseases is intimately linked with the changes humanity is making to the planet. Climate change, urbanization, habitat destruction, global travel, agricultural intensification, pollution, and biodiversity loss all converge to create new opportunities for pathogens to thrive and spill over into human populations. As global change accelerates, so does the risk of future epidemics and pandemics.

Efforts to mitigate these risks must take a holistic, One Health approach – recognizing that the health of people is connected to the health of animals and our shared environment. Policies that promote sustainable development, protect biodiversity, improve surveillance, strengthen healthcare systems, and reduce inequities are essential to managing the complex relationship between global change and infectious disease.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.