Autoimmune diseases occur when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy cells and tissues, failing to distinguish between “self” and “non-self-molecules.” Normally, the immune system protects the body against infections by targeting harmful pathogens such as bacteria and viruses (which are antigens or non-self-molecules that invades the body). However, in autoimmune disorders, this defense mechanism becomes overactive or misdirected, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. There are over 80 types of autoimmune diseases, affecting different organs and systems of the body, including the skin, joints, thyroid, and digestive tract.

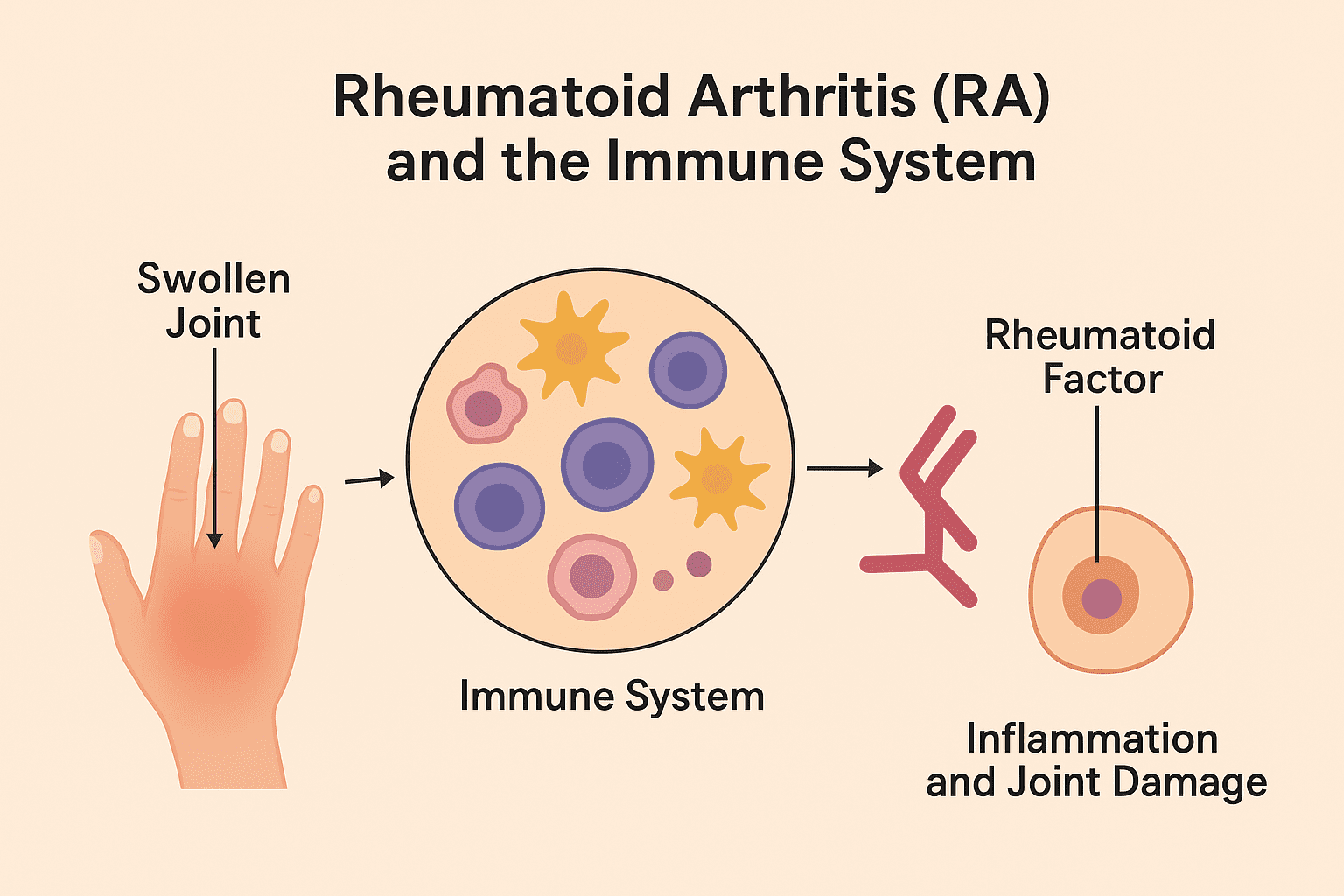

One of the most well-known autoimmune diseases is rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA primarily affects the joints, where the immune system targets the synovial membrane – the lining of joints – causing painful swelling, stiffness, and erosion of bone and cartilage. Over time, this can lead to joint deformity and disability if not properly managed. The exact cause of RA remains unclear, but it is thought to result from a combination of genetic susceptibility, hormonal factors, and environmental triggers such as infections or smoking.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly targets the synovium. Synovium is the thin membrane lining the joints. RA, an immune-mediated attack, triggers persistent inflammation, leading to pain, swelling, and progressive destruction of cartilage and bone. Over time, uncontrolled inflammation can result in joint deformity and loss of function. Unlike osteoarthritis, which primarily results from mechanical wear and tear, RA typically affects joints symmetrically, and this implies that if one knee or hand joint is affected, the corresponding joint on the opposite side is usually affected as well.

RA as aforesaid is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder characterized primarily by persistent synovial inflammation, progressive joint destruction, and varying degrees of extra-articular involvement. It represents one of the most common autoimmune diseases, affecting approximately 0.5–1% of the global population. The disease is notable for its symmetrical involvement of small joints, particularly those of the hands, wrists, and feet and for its potential to cause significant disability, deformity, and reduced quality of life if untreated.

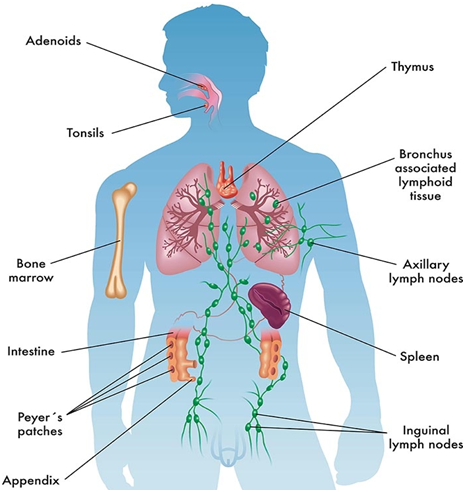

The hallmark of RA is a chronic synovitis mediated by autoreactive T and B cells, leading to pannus formation, cartilage erosion, and bone resorption. In addition to joint pathology, systemic manifestations may involve the skin, eyes, cardiovascular system, and lungs. Microbiological and immunological studies have elucidated several potential triggers and mechanisms ranging from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitansinvolvement to genetic predispositions within the HLA-DRB1 locus of the immune system.

Etiology and Biology of RA

Several factors are responsible for the initiation of RA.

Genetic Factors

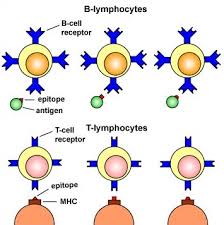

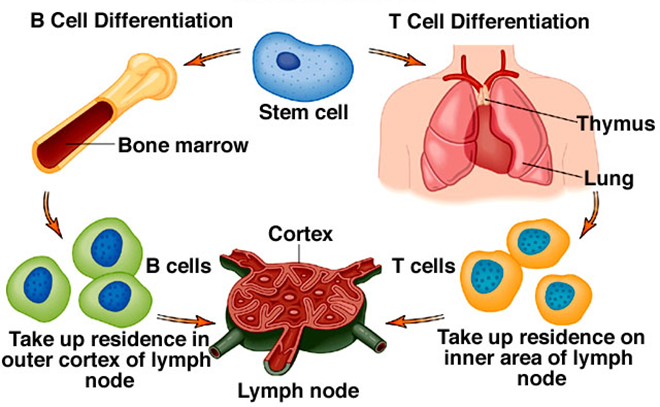

Genetic predisposition contributes significantly to the development of RA. The HLA-DRB1 gene, particularly alleles encoding the “shared epitope” (SE) motif at positions 70–74 of the DRβ1 chain, confers the strongest genetic risk. The SE hypothesis suggests that these motifs facilitate presentation of arthritogenic self-peptides to CD4+ T cells.

Other non-HLA genes implicated include PTPN22 (a lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase gene influencing T-cell activation), STAT4, CTLA4, TRAF1-C5, and PADI4, the latter being crucial for protein citrullination.

Environmental Factors

Several environmental triggers for RA include:

- Smoking: Smoking is the most well-established risk factor, particularly in HLA-DRB1 SE carriers. Smoking induces citrullination of lung proteins and promotes formation of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs).

- Microbial factors: Infections caused by microbes including chronic infections, especially Porphyromonas gingivalis (a periodontal pathogen expressing bacterial peptidylarginine deiminase), and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, have been linked to RA pathogenesis through induction of protein citrullination.

- Hormonal influences: The female predominance (3:1 ratio) and disease modulation during pregnancy suggest hormonal involvement, possibly through estrogen’s immunomodulatory effects.

- Other factors: Air pollutants, silica exposure, diet, and gut dysbiosis are other factors that also influence disease susceptibility in RA patients.

Immunologic and Microbiologic Aspects of RA

As aforesaid, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by chronic synovial inflammation, progressive joint destruction, and systemic immune dysregulation. A hallmark of RA is the loss of self-tolerance by the immune system, leading to sustained autoimmunity. Central to its immunopathology is the presence of autoantibodies, including rheumatoid factor (RF). RF is an IgM antibody directed against the Fc portion of IgG and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) that recognize citrullinated epitopes on self-proteins. The generation of ACPAs reflects a breach in central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms, with autoreactive B and T cells contributing to a self-perpetuating inflammatory milieu. These autoantibodies (RFs) form immune complexes that activate complement pathways and Fc receptor-mediated responses, driving synovial inflammation and joint damage.

Beyond intrinsic immune dysregulation, mounting evidence implicates the microbiome as a key contributor to RA pathogenesis. Specific bacterial species, particularly those capable of post-translational modifications, can create neo-epitopes that mimic host antigens, triggering autoimmunity. For example, Porphyromonas gingivalis expresses peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD), which citrullinates bacterial and host proteins, potentially breaking immune tolerance and initiating ACPA production. Similarly, gut-resident bacteria, including Prevotella copri, have been associated with RA onset and disease activity, suggesting that mucosal microbial dysbiosis can modulate systemic autoimmunity. Microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, can influence T cell differentiation, skewing the balance between pro-inflammatory Th17 cells and regulatory T cells, thereby impacting immune homeostasis.

The interaction between the microbiome and the host immune system may thus represent a bidirectional relationship: aberrant immunity in RA alters mucosal barriers and microbial composition, while microbial cues perpetuate autoreactive responses. This crosstalk highlights the potential of targeting microbial communities or their metabolites to modulate autoimmunity. Moreover, environmental factors, including diet, antibiotics, and periodontal disease, can influence microbial composition and enzymatic activity, further shaping the immune landscape.

RA emerges as a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and microbial influences. Autoantibody production and chronic inflammation reflect intrinsic immune defects, while microbial post-translational modifications and dysbiosis provide exogenous triggers that breach tolerance. Understanding this immuno-microbiologic nexus offers opportunities for novel therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring immune homeostasis and preventing or attenuating disease progression.

Pathogenesis of RA

The pathogenesis of RA involves a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and dysregulated immune responses leading to chronic inflammation and joint destruction. The establishment of RA include several phases: initiation, production of autoantibody, inflammation of the synovial, and destruction of tissues.

Initiation Phase

In genetically susceptible individuals, environmental factors such as smoking or infection promote post-translational modification of proteins through citrullination. These neo-antigens are presented to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and recognized by autoreactive CD4+ T cells. The earliest immune activation may occur at mucosal sites such as the lungs or oral cavity before clinical arthritis develops.

Autoantibody Production

In this stage, activated B cells differentiate into plasma cells that produce autoantibodies – RF and ACPAs. These antibodies can form immune complexes that activate complement, amplify inflammation, and predict disease severity. ACPA positivity often precedes clinical onset by several years, marking the transition from pre-clinical to established disease.

Synovial Inflammation

Activated CD4+ T cells infiltrate the synovium and release cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), recruiting macrophages and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS). These cells release IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), perpetuating inflammation and tissue degradation. The hyperplastic synovial tissue known as pannus invades cartilage and bone, eroding articular structures. Osteoclast activation, mediated via RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand) produced by FLS and T cells, drives bone resorption.

Chronicity and Tissue Destruction

The chronic inflammatory milieu in RF cases sustains itself through positive feedback loops involving cytokines, chemokines, and cellular interactions. Angiogenesis and neovascularization enable leukocyte recruitment and pannus expansion. Over time, cartilage loss, bone erosion, and joint deformities (ulnar deviation, swan neck, and boutonnière deformities) develop.

Extra-articular Manifestations of RA

RA can involve multiple organ systems, thus causing the following clinical conditions in different organs of the body:

- Rheumatoid nodules (granulomatous lesions, often subcutaneous)

- Vasculitis, leading to skin ulcers or neuropathy

- Pulmonary disease (interstitial lung disease, pleural effusion)

- Cardiovascular involvement, contributing to increased mortality

- Ocular (scleritis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca)

- Hematologic (anemia of chronic disease, Felty’s syndrome-RA, splenomegaly, neutropenia)

Clinical Features of RA

RA typically presents as a symmetric, polyarticular arthritis involving small joints. Key features include:

- Morning stiffness lasting >1 hour

- Swelling, warmth, and tenderness of joints (especially MCP, PIP, wrists)

- Systemic symptoms: fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss, malaise

- Chronic course: alternating exacerbations and remissions

- Deformities in long-standing disease: ulnar deviation, swan neck, boutonnière, and Z-thumb deformity

Disease progression varies; while some patients experience mild, intermittent symptoms, others develop aggressive, erosive arthritis with extra-articular manifestations.

Laboratory Diagnosis of RA

Diagnosis of RA is clinical but supported by laboratory and imaging findings. Some diagnostic pursuits are as follows:

Serologic Tests

- Rheumatoid Factor (RF): RF is present in about 70–80% of patients. High titers of RF correlate with severe disease but are not specific because they can appear in infections, aging, and other autoimmune diseases.

- Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies (ACPAs): ACPAs is highly specific (~95%) for RA and can appear years before disease onset. It is detected by anti-CCP (cyclic citrullinated peptide) ELISA tests.

- Antinuclear antibodies (ANA): ANA is occasionally positive, particularly in overlap syndromes.

Acute-Phase Reactants

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are elevated, reflecting systemic inflammation. Both ECR and CRP are important biomarkers that help clinicians to assess disease activity and response to therapy.

Synovial Fluid Analysis

RA synovial fluid is turbid, with increased leukocyte count (5,000–50,000/mm³), predominantly neutrophils. Glucose is mildly reduced, and complement levels are decreased. Microscopy shows absence of crystals (differentiating from gout/pseudogout).

Imaging

- X-ray: Early changes include periarticular osteopenia, soft tissue swelling, and joint space narrowing. Late findings show erosions and deformities.

- Ultrasound and MRI: Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are even more sensitive for early synovitis, effusions, and bone marrow edema.

Treatment of RA

The goal of RA management is to achieve disease remission or low disease activity, prevent joint damage, and maintain function. The modern approach follows the “treat-to-target” principle with early, aggressive intervention.

Non-Pharmacologic Management: This include:

- Patient education and counseling on disease nature and adherence

- Physical and occupational therapy to maintain joint mobility

- Lifestyle modification including smoking cessation, balanced diet, and exercise

- Psychosocial support for chronic disease adaptation

Pharmacologic Treatment

a. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs provide symptomatic relief of pain and stiffness but do not alter disease progression. Common NSAIDs drugs include ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib.

b. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids such as prednisone are used for acute flares or as bridging therapy. Prednisone suppresses inflammation via multiple pathways but carries risks (osteoporosis, hypertension, infection).

c. Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

The cornerstone of RA therapy are DMARDs.

Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) include:

- Methotrexate (MTX): MTX are the first-line agents used in RA therapy. They inhibit dihydrofolate reductase and AICAR transformylase, reducing lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production.

- Sulfasalazine: Sulfasalazine produces immunomodulatory effects; useful in combination therapy.

- Hydroxychloroquine: Hydroxychloroquine are antimalarial drugs with lysosomal stabilization properties. They are used in mild RA disease or as combination regimens.

- Leflunomide: Leflunomide are known to inhibit pyrimidine synthesis, reducing T-cell proliferation in RA disease conditions.

Combination Therapy: MTX with other csDMARDs or biologics enhances efficacy of therapy in RA disease conditions.

d. Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs)

These drugs target specific cytokines or immune pathways:

- TNF-α inhibitors: Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab, Certolizumab, Golimumab.

- IL-6 receptor blockers: Tocilizumab, Sarilumab.

- Co-stimulation modulators: Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig fusion protein inhibiting T-cell activation).

- B-cell depletion: Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody).

These agents dramatically improve outcomes but increase infection risk, particularly reactivation of tuberculosis and hepatitis B.

e. Targeted Synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs)

Small-molecule inhibitors such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors including Tofacitinib, Baricitinib, Upadacitinib are known to block intracellular cytokine signaling. Effective in refractory RA but require infection and malignancy monitoring.

Epidemiology of RA

RA affects approximately 0.5–1% of adults globally, with variations across regions and ethnicities. Disease progression in RA cases is usually affected by gender, age, geography.

- Gender: Women are affected three times more than men.

- Age: Peak onset between 30–50 years, though it can occur at any age.

- Geography: Higher prevalence in northern Europe and North America; lower rates in rural Africa and Asia, though underdiagnosis is possible.

- Trends: With early diagnosis and DMARD use, disability rates are declining, but cardiovascular mortality remains elevated.

- Infections and microbiota: Recent epidemiologic studies implicate the oral and gut microbiome in susceptibility, highlighting the microbiological dimension of RA.

Prevention and Control of RA

Primary prevention measures for RA include:

- Smoking cessation: Most effective modifiable factor.

- Oral health maintenance: Reducing P. gingivalis colonization may lower risk.

- Occupational control: Minimize silica exposure.

- Vaccinations: Prevent infections that may trigger immune activation.

Secondary prevention measures for RA include:

- Early detection of pre-clinical autoimmunity (e.g., ACPA-positive individuals).

- Screening high-risk groups (family history, HLA-DRB1 carriers, smokers).

- Prompt initiation of DMARDs at first clinical evidence of synovitis.

Tertiary prevention measures for RA include:

- Regular monitoring for disease activity and drug toxicity.

- Rehabilitation and joint protection strategies.

- Cardiovascular risk management: Control hypertension, lipids, and glucose.

- Infection prophylaxis in immunosuppressed patients.

Public health programs targeted at RA disease prevention usually emphasize early referral, multidisciplinary management, and patient education as non-pharmaceutical approaches to reduce disease burden.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a typical autoimmune disease illustrating the intersection of genetics, environment, and immunology. It begins as a localized mucosal immune dysregulation that evolves into a systemic, joint-destructive process. Over the past two decades, breakthroughs in understanding the molecular and cellular basis of inflammation have transformed RA from a crippling disease to one that is often controllable with early and targeted intervention. Despite progress, challenges remain. These include incomplete remission in many patients, high treatment costs, and increased infection and cardiovascular risks. RA exemplifies how chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors converge to produce complex disease conditions.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.