Digital PCR (dPCR) is a method of quantifying nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) targets without standard curves by dividing the bulk reaction into thousands of smaller, independent reactions.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is one of the most transformative molecular biology techniques ever developed. Since its invention in the 1980s, PCR has revolutionized how scientists detect and quantify nucleic acids. Over the decades, PCR technology has evolved through three main generations: conventional PCR, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), and digital PCR (dPCR). Each successive generation has improved on precision, quantification accuracy, and sensitivity.

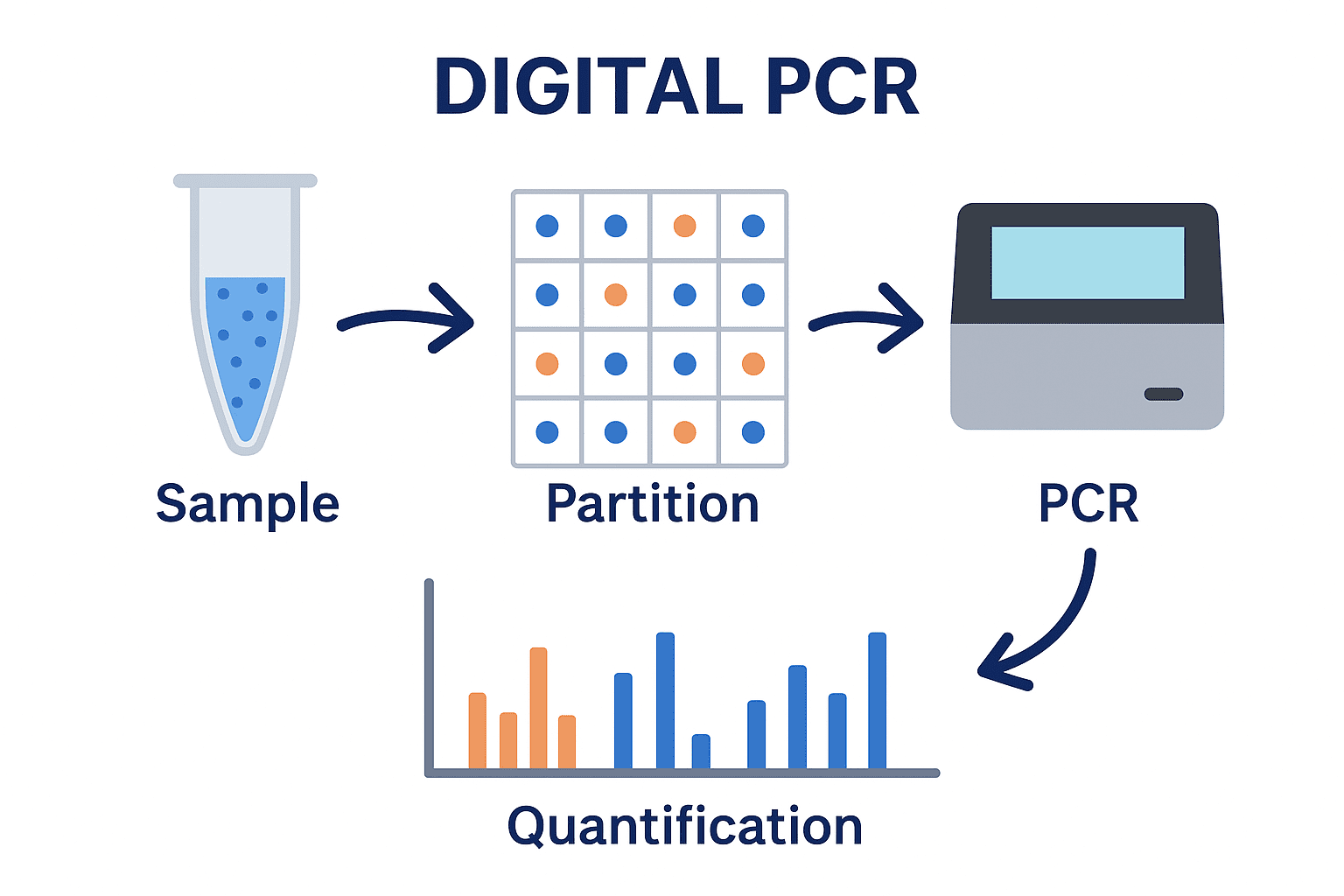

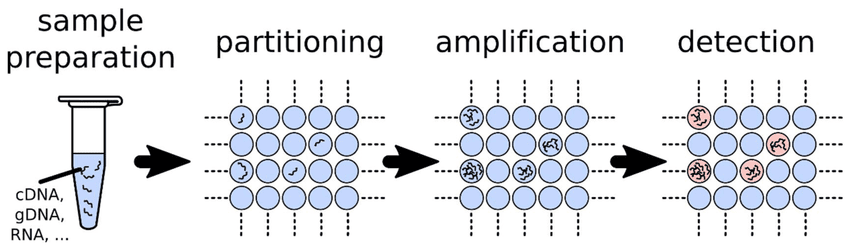

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents the third generation of PCR-based quantification methods (Figure 1). It enables absolute quantification of nucleic acids without the need for calibration curves or reference standards as is the case with qPCR. Unlike qPCR, which measures the accumulation of fluorescence during amplification, dPCR divides a sample into thousands to millions of partitions and performs PCR in each partition separately. The partitions are classified as positive(if amplification occurs) or negative (if no amplification occurs). The number of target DNA molecules in the original sample is then determined statistically, using Poisson distribution principles.

This innovation in dPCR offers extremely precise and sensitive nucleic acid quantification which allows for the detection of single-copy targets or rare mutations among a vast excess of wild-type DNA. Over the last decade, dPCR has gained traction in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, cancer research, infectious disease detection, and genetic studies.

Principle of Digital PCR

The concept underlying digital PCR (dPCR) is simple yet powerful. Traditional PCR and qPCR reactions amplify a bulk mixture of DNA, making quantification indirect. In contrast, dPCR isolates single DNA molecules in thousands of miniature reaction chambers. Each chamber then functions as an independent PCR micro-reactor.

Partitioning of the sample in dPCR experiment

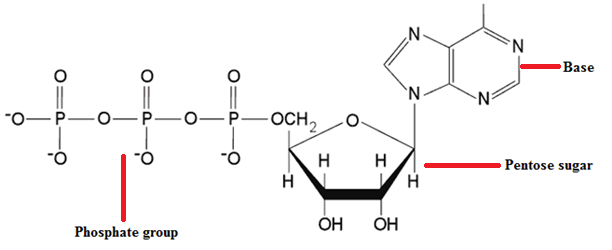

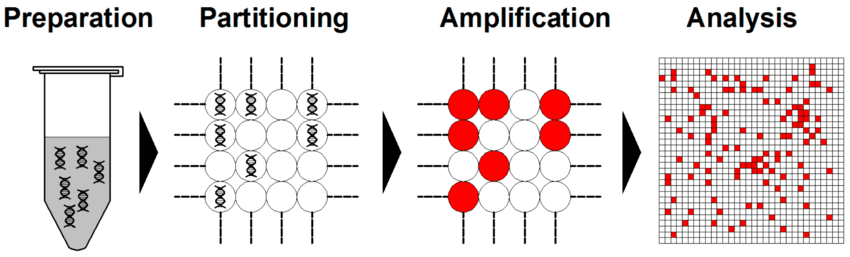

In dPCR, the sample mixture containing the nucleic acid template, primers, probes, nucleotides, and polymerase is divided into many individual partitions, usually numbering from 10,000 to several million (Figure 2). Partitioning can be achieved using droplets, microfluidic chambers, or microwells. The objective of partitioning is to distribute DNA molecules randomly across partitions, following a Poisson distribution, such that most partitions contain zero or onetarget molecule. The partitioning step in dPCR is crucial because it converts the analog fluorescence signal (as in qPCR) into binary digital signals either “1” (target detected) or “0” (no target).

Cao et al. (2020). Digital PCR as an Emerging Tool for Monitoring of Microbial Biodegradation. Molecules, 25(3), 706. Quan et al. dPCR: A Technology Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18041271 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25030706

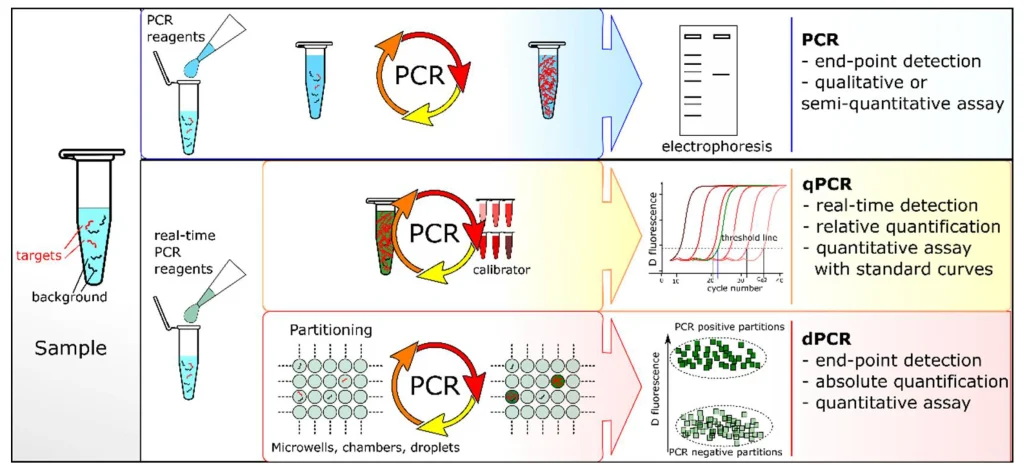

In conventional PCR, the amplification products are analyzed at the end of the reaction (end-point PCR) by gel electrophoresis and detected after fluorescent staining (Figure 3). qPCR and dPCR use the same amplification reagents and fluorescent labeling systems. In qPCR, the amount of amplified DNA is measured at each cycle during the PCR reaction, i.e., in real-time. The ‘absolute’ quantity of target sequence is interpolated using a standard curve generated with a calibrator.

But in dPCR, the sample is first partitioned into many sub-volumes (in microwells, chambers or droplets) such that each partition contains either a few or no target sequences. After PCR, the proportion of amplification-positive partitions serves to calculate the concentration of the target sequence using Poisson’s statistics. dPCR is a method of absolute nucleic acid quantification that hinges on the detection of end-point fluorescent signals and the enumeration of binomial events (absence (0) or presence (1) of fluorescence in a partition).

This statistical foundation permits to identify the parameters that constraint the performance metrics of this analytical method. dPCR is theoretically advantageous over qPCR given effective means to perform sample partitioning and target amplification of single molecules.

Quan et al. dPCR: A Technology Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18041271

PCR Amplification process in dPCR

Once partitioned, each reaction chamber undergoes thermal cycling, just like in conventional PCR. If a partition contains at least one copy of the target sequence, the PCR reaction proceeds, generating detectable fluorescence from probe hydrolysis (e.g., using TaqMan probes). Partitions without the target remain dark.

Detection and Quantification process in dPCR

After amplification, the fluorescence of each partition is read using an optical detector. The system counts the number of positive partition (fluorescence) and negative partition (no fluorescence). The fraction of positive partitions (p)allows estimation of the average number of target molecules per partition (λ) using the Poisson equation:

λ = – ln (1 – p)

From λ and the known partition volume, the absolute concentration of the target in the original sample can be calculated. This statistical correction accounts for partitions that may contain more than one target molecule.

λ = average number of target molecules per partition

P = Fraction of positive partitions. It is the proportion of partitions showing amplification (fluorescence). P(0) is the probability that a partition received zero molecules

Ln = Natural logarithm. Used to reverse the exponential relationship in the Poisson model.

(1 – p) = Fraction of negative partitions. Represents the proportion of partitions that received zero target molecules.

–ln(1 – p) = Correction factor. Converts the observed positive fraction into an estimate of the average molecules per partition, accounting for multiple occupancy.

Digital Counting in dPCR

Because every partition is classified as “positive” or “negative,” the total number of positive partitions directly reflects the absolute number of target molecules. This digital nature eliminates the need for calibration curves or reference genes, providing a truly absolute quantification of nucleic acid targets.

Workflow of Digital PCR

The digital PCR workflow comprises several major steps, each critical for accuracy and reproducibility. The sample preparation process; as well as the reaction mixture setup must be properly planned in advance.

Sample Preparation for dPCR experiment

DNA or RNA is extracted from the sample (e.g., blood, tissue, environmental sample) using standard nucleic acid extraction methods. It is best to use the Qiagen kit or any other commercially available kit for DNA extraction. Purity is vital in extracting DNA for dPCR experiment since – contaminants like proteins, humic acids, or phenol can inhibit polymerase activity and partition formation.

If RNA is the target, it must first be reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) before digital amplification. This process is known as reverse transcription digital PCR (RT-dPCR).

Reaction Setup for dPCR experiment

The reaction mix for dPCR experiment includes:

- DNA template or cDNA template (if the target is RNA)

- Sequence-specific primers (forward and reverse)

- Fluorescent probes (e.g., TaqMan probes)

- dNTPs

- MgCl₂

- DNA polymerase (commonly hot-start Taq polymerase)

- Reaction buffer

The mix for dPCR experiment is similar to that used in qPCR, except that no reference dye or calibration standards are required.

Partition Generation in dPCR Experiment

Partitioning in dPCR can occur through several mechanisms depending on the platform:

- Droplet-based systems: The mixture is emulsified into thousands of uniform droplets suspended in oil (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200).

- Chip-based systems: Microfluidic chips physically separate the reaction mix into thousands of microchambers (e.g., QuantStudio Absolute Q).

- Microwell-based systems: Arrays of tiny wells on a plate or slide hold discrete reaction volumes.

The goal of partitioning in dPCR is to generate many independent partitions with uniform size and volume to ensure statistical reliability.

Thermal Cycling in dPCR

The partitions in dPCR are subjected to thermal cycling conditions similar to conventional PCR. The DNA is denatured, primers anneal, and polymerase extends the DNA strands. Each partition acts as an individual PCR reactor.

Fluorescence Detection in dPCR

After amplification, partitions are analyzed using a fluorescence reader. Droplet readers flow droplets past a laser detector, while chip systems use imaging scanners to measure fluorescence intensity across all partitions. Each partition is classified as positive or negative based on fluorescence thresholding.

Data Analysis of dPCR Output

dPCR generates digital data. The digital data (which are the number of positive and negative partitions) is processed by proprietary software that applies Poisson correction to estimate the absolute concentration of target molecules per microliter. Results are typically reported as:

- Copies per microliter of reaction,

- Copies per nanogram of DNA, or

- Copies per cell (for genomic studies).

Types of Digital PCR Platforms

Digital PCR technologies can be categorized based on how they partition and process samples. Droplet digital PCR, chip-based digital PCR and microwell-array digital PCR are some of the available dPCR currently applied in diverse medical, biomedical, biological and environmental research.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

Droplet digital PCR is currently the most widely used form of dPCR. It partitions the PCR mixture into tens of thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets using a water-in-oil emulsion. Each droplet acts as an independent PCR reactor.

Workflow of ddPCR:

- Droplet generation

- PCR amplification in droplets

- Droplet reading by fluorescence detector

- Poisson-based quantification

Examples of ddPCR

- Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System

- Bio-Rad QX One Automated dPCR System

Advantages of ddPCR

- High precision

- Excellent tolerance to PCR inhibitors

- High partition number (~20,000 droplets)

Limitations of ddPCR

- Requires emulsification and droplet stabilization steps

- End-point measurement only

Chip-Based Digital PCR

Chip-based digital dPCR utilize microfluidic technology to partition samples into thousands of microchambers on a solid chip or cartridge.

Examples of chip-based digital PCR

- Thermo Fisher QuantStudio Absolute Q

- Stilla Naica System

Advantages of chip-based digital PCR

- No oil emulsification (simpler workflow)

- Highly uniform partition size

- Easy multiplexing

Limitations of digital PCR

- More expensive chips

- Limited scalability compared to droplet systems

Microwell-Array dPCR

Microwell-array dPCR use physical well arrays to separate reaction mixtures into discrete wells (e.g., Fluidigm Biomark HD). Fluorescence detection in microwell-array dPCR is typically done through imaging.

Advantages of microwell-array dPCR

- Visual verification of partitions

- High multiplex capacity

Limitations of microwell-array dPCR

- Lower partition numbers compared to droplet systems

- Higher cost per run

Advantages of Digital PCR

Digital PCR offers numerous advantages over both conventional and real-time PCR. Some of the advantages of dPCR include absolute quantification, high sensitivity and precision, resistance to PCR inhibitors, reproducibility, multiplexing capability; and dPCR is also ideal for rare event detection.

Absolute Quantification

Unlike qPCR, which provides relative quantification based on standard curves, dPCR directly counts target molecules, providing absolute copy numbers without external standards or standard curves as is the case with qPCR.

High Sensitivity and Precision

The partitioning process in dPCR isolates rare targets from background DNA, significantly improving sensitivity and precision. It can reliably detect single-copy targets or low-frequency mutations (as low as 0.01%).

Resistance to PCR Inhibitors

Because dPCR measures end-point amplification in individual partitions, the influence of inhibitors (e.g., humic substances, heme) is minimized, improving robustness when analyzing challenging samples like soil or blood.

Reproducibility

Partitioning in dPCR reduces variability between reactions. The results are highly reproducible across replicates and laboratories.

Multiplexing Capability

By using multiple fluorescent probes, dPCR can quantify several targets in a single reaction. For example, detecting multiple pathogens or resistance genes simultaneously in a particular sample.

Ideal for Rare Event Detection

dPCR is ideal for measuring or detecting rare events in a sample. Applications such as detecting rare mutations in cancer, viral variants, or low-level pathogen loads benefit from the superior sensitivity of dPCR.

Limitations of Digital PCR

Despite its advantages, dPCR has several constraints:

- Cost: Equipment and consumables are more expensive than those for qPCR.

- Throughput: Limited sample throughput; not ideal for large-scale screening.

- Dynamic Range: Narrower (typically 4–5 logs) compared to qPCR (7–8 logs).

- Complexity: Requires partitioning devices and fluorescence readers.

- Data Interpretation: Needs software-based Poisson correction, which adds computational requirements.

Comparison of Digital PCR with RT-qPCR

Since RT-qPCR (real-time quantitative PCR) has been the gold standard for nucleic acid quantification for over two decades, it’s essential to understand how dPCR compares in terms of principle, workflow, performance, and applications.

Table 1. Differences between RT-qPCR and dPCR

| Feature | RT-qPCR | Digital PCR |

| Quantification Basis | Measures fluorescence during the exponential phase of PCR. Quantification is relative to standard curves. | Measures binary fluorescence (positive/negative) at endpoint, followed by Poisson analysis for absolute quantification. |

| Detection | Real-time monitoring using Ct (cycle threshold) values. | Endpoint fluorescence detection after amplification. |

| Calibration | Requires external standard curves. | No calibration required; provides absolute copy number. |

| Quantitative Range | Broad (up to 8 orders of magnitude). | Narrower (typically 4–5 orders of magnitude). |

Applications of Digital PCR

Digital PCR has broad utility across multiple scientific disciplines. dPCR is applied in clinical diagnostics, infectious disease monitoring, environmental microbiology, virology, forensic and biodiversity studies and food safety and agriculture.

Clinical Diagnostics

- Cancer mutation detection: dPCR can identify low-frequency mutations in oncogenes (e.g., KRAS, EGFR) within cell-free DNA.

- Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA): Enables quantification of ctDNA for minimal residual disease monitoring.

- Copy number variation (CNV): Accurate quantification of gene copy numbers in genetic disorders.

- Pathogen detection: Absolute quantification of viral or bacterial load without reference standards.

Infectious Disease Monitoring

dPCR can precisely measure pathogen load in blood or tissue. This is usally essential for diseases like HIV, hepatitis, and COVID-19. It allows quantification even in the presence of PCR inhibitors and at very low viral loads.

Environmental Microbiology

In environmental applications, dPCR quantifies antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), pathogens, and microbial populations in soil, water, and wastewater. It’s especially valuable when inhibitors like humic acids hinder qPCR accuracy.

Food Safety and Agriculture

dPCR ensures accurate detection of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), foodborne pathogens, and allergens, even at trace levels. This helps to ensure reliable food safety for all and a sustainable agriculture.

Virology

During outbreaks (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 – the causative agent of COVID19), dPCR proved valuable for detecting low viral loads and confirming qPCR borderline results. It has been used for quantifying viral RNA with higher precision than RT-qPCR.

Forensic and Biodiversity Studies

Because of its high sensitivity, dPCR can analyze degraded DNA from forensic samples or ancient DNA from archaeological findings.

Digital PCR (dPCR) is a landmark advancement in molecular biology that transforms the way nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) are quantified. By partitioning samples into thousands of micro-reactions and digitally counting positive signals, it achieves absolute, precise, and highly sensitive quantification of DNA and RNA targets.

Compared with RT-qPCR, dPCR provides greater accuracy, reproducibility, and resistance to inhibitors, making it ideal for challenging samples and low-abundance targets. While qPCR remains dominant for routine, high-throughput applications, dPCR is increasingly adopted where quantification accuracy is critical – such as clinical diagnostics, mutation detection, environmental monitoring, and AMR surveillance.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.