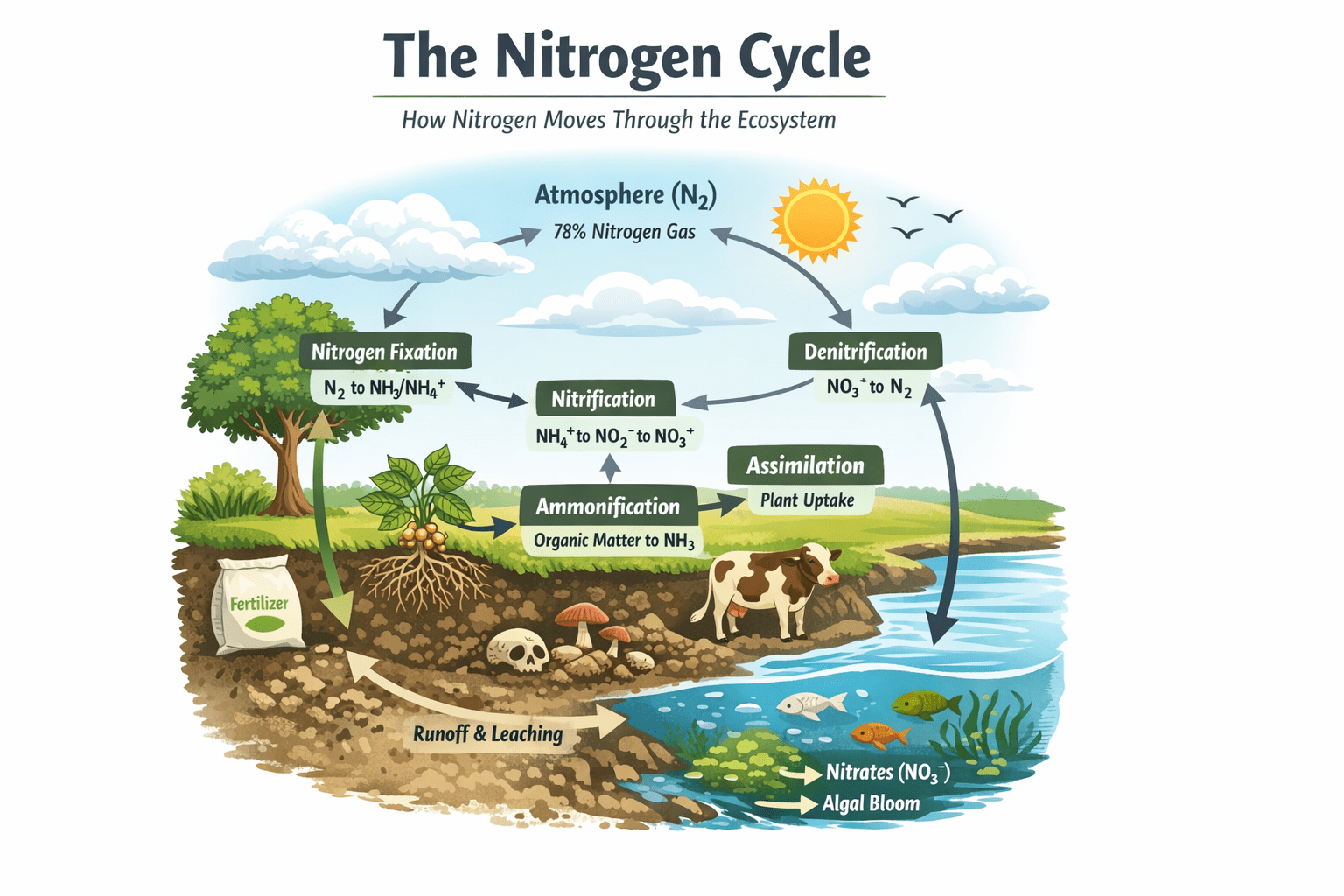

The nitrogen cycle is a fundamental biogeochemical process through which nitrogen is exchanged between the earth’s atmosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere. This cycle governs the transformations of nitrogen and nitrogen-containing compounds in the environment, ensuring that this essential element is available in forms that can sustain life. Nitrogen is a critical component of proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids, including deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), which are central to genetic information and cellular function. Despite its abundance constituting approximately 78% of the atmosphere – molecular nitrogen (N₂) is largely inert and unavailable to most living organisms without being chemically converted into biologically usable forms. This conversion and continual recycling of nitrogen is the core function of the nitrogen cycle. Understanding this cycle is essential not only for ecology but also for agriculture, environmental management, and climate science.

Nitrogen exists in multiple chemical forms in nature, including inorganic compounds such as ammonia (NH₃), ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrites (NO₂⁻), and nitrates (NO₃⁻), as well as organic compounds including amino acids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Each form plays a distinct role in ecosystems, and the availability of nitrogen in these forms directly affects plant growth, microbial activity, and animal nutrition. Plants are primary consumers of inorganic nitrogen, absorbing it from soils and water to synthesize essential biomolecules. Animals obtain nitrogen indirectly by consuming plants or other animals. Microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi, mediate the conversion of nitrogen between different chemical states, ensuring a continuous flow of this vital element through the ecosystem.

The Importance of Nitrogen in Ecosystems

Nitrogen is indispensable for life. In plants, nitrogen deficiency leads to stunted growth, chlorosis (yellowing of leaves), reduced photosynthetic activity, and diminished yield. Adequate nitrogen availability ensures the synthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and chlorophyll molecules, which are critical for cellular metabolism and energy capture. Animals, in turn, depend on dietary nitrogen obtained from plants or other animals to synthesize their own proteins and nucleic acids. Microorganisms play a dual role: they recycle nitrogen from organic matter and facilitate its conversion into forms usable by plants. The nitrogen cycle thus underpins ecosystem productivity, biodiversity, and stability.

The anthropogenic manipulation of nitrogen, particularly through agricultural fertilization, has profound ecological consequences. Excessive application of organic or inorganic fertilizers can lead to nitrogen leaching into water bodies, triggering eutrophication. This process stimulates excessive growth of algae and aquatic plants, which eventually die and decompose, depleting dissolved oxygen and threatening aquatic life. Therefore, effective management of nitrogen inputs is critical for both crop productivity and environmental sustainability.

Sources of Nitrogen in Ecosystems

Nitrogen enters terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems through multiple pathways:

- Atmospheric Deposition: Nitrogen gas (N₂) in the atmosphere can enter the soil through natural processes, including precipitation, lightning, and microbial fixation.

- Biological Nitrogen Fixation: Certain plants, known as nitrogen fixers particularly legumes (e.g., alfalfa, clover, beans) and non-leguminous plants such as ceanothus harbor symbiotic bacteria capable of converting N₂ into ammonia (NH₃). These bacteria, including genera such as Rhizobium, Azotobacter, and Clostridium, possess nitrogenase enzymes that catalyze the reduction of atmospheric nitrogen into bioavailable forms.

- Human Activities: Agricultural and industrial practices introduce nitrogen into soils via chemical fertilizers (e.g., ammonium nitrate, urea) and organic fertilizers (e.g., compost, manure). These inputs accelerate crop growth but must be carefully managed to prevent environmental pollution.

- Decomposition: Nitrogen from decaying organic matter and animal waste is released back into soils as ammonia through microbial activity, contributing to the nitrogen pool available for plant and microbial use.

Major Processes in the Nitrogen Cycle

The nitrogen cycle involves several interconnected biological and chemical processes that convert nitrogen between its various forms. These processes include nitrogen fixation, nitrification, denitrification, ammonification, mineralization, and assimilation.

Nitrogen Fixation

Nitrogen fixation is the process by which atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) is converted into ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium (NH₄⁺), which can be used by plants and microorganisms. This process is catalyzed by nitrogenase enzymes found in certain bacteria and archaea. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria may be free-living in the soil (Azotobacter, Clostridium) or symbiotic within plant root nodules (Rhizobium in legumes). Cyanobacteria such as Anabaena and Nostoc can fix nitrogen in aquatic and terrestrial environments.

Nitrogen fixation is critical because it transforms inert atmospheric nitrogen into reactive forms that sustain biological productivity. Industrially, nitrogen fixation is also achieved through the Haber-Bosch process, which produces synthetic fertilizers from N₂ and hydrogen, but this method consumes large amounts of energy and has environmental implications.

Nitrification

Nitrification is a two-step microbial process in which ammonia is oxidized into nitrites and then nitrates, both of which are essential for plant nutrition:

- Ammonia Oxidation: Ammonia (NH₃) is oxidized to nitrite (NO₂⁻) by bacteria such as Nitrosomonas and Nitrosococcus.

- Nitrite Oxidation: Nitrite (NO₂⁻) is further oxidized to nitrate (NO₃⁻) by bacteria such as Nitrobacter.

Nitrification increases the availability of nitrogen in a form that plants can absorb through their root systems. Nitrate, being highly soluble, can be transported in soil water and assimilated efficiently by crops. However, excessive nitrates can leach into groundwater, causing pollution and contributing to health risks such as methemoglobinemia (“blue baby syndrome”) in infants.

Denitrification

Denitrification is the reduction of nitrate (NO₃⁻) and nitrite (NO₂⁻) back to molecular nitrogen (N₂) or nitrous oxide (N₂O), returning nitrogen to the atmosphere. This process is performed by heterotrophic bacteria, including Paracoccus denitrificans, Pseudomonas species, and Thiobacillus denitrificans, under anaerobic conditions.

Denitrification is essential for maintaining the balance of nitrogen in ecosystems. It prevents excessive nitrate accumulation in soils, which can lead to nutrient imbalances and water pollution. However, incomplete denitrification can produce N₂O, a potent greenhouse gas, linking the nitrogen cycle to climate change.

Ammonification

Ammonification, also known as mineralization, is the microbial conversion of organic nitrogen in dead organisms or waste products into inorganic ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium (NH₄⁺). Fungi and bacteria decompose proteins, nucleic acids, and other nitrogen-containing compounds, releasing ammonia into the soil. This process replenishes nitrogen in forms available to plants and microbes, sustaining the continuous flow of the nitrogen cycle.

Ammonification and nitrification together constitute the mineralization process, in which organic matter is fully decomposed, returning nitrogen to the ecosystem in bioavailable forms.

Assimilation

Assimilation refers to the uptake and incorporation of nitrogen into the tissues of plants and microorganisms. Plants absorb nitrates (NO₃⁻) or ammonium (NH₄⁺) from the soil through root hairs and convert them into amino acids, nucleotides, and proteins. Heterotrophic organisms, including animals and microbes, acquire nitrogen by consuming plants or other organisms. This transfer of nitrogen from producers to consumers integrates nitrogen into food webs, supporting growth, reproduction, and metabolic activities.

Mineralization and Recycling

Mineralization is the breakdown of complex organic matter into simpler inorganic compounds, which re-enters the soil and water. Through decomposition, nitrogen locked in proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids of dead organisms and animal excreta is released as ammonium (NH₄⁺) or other inorganic compounds. Microbial decomposers, including fungi and bacteria, drive this process, ensuring nitrogen continues to circulate through ecosystems. This recycling maintains soil fertility, supports plant growth, and sustains microbial communities.

Nitrogen in Aquatic Ecosystems

In aquatic systems, nitrogen dynamics differ slightly from terrestrial environments. Nitrogen enters water bodies through rainfall, runoff containing fertilizers, and atmospheric deposition. Ammonia, nitrites, and nitrates undergo transformations similar to those in soil. However, excess nitrogen can disrupt aquatic ecosystems by promoting eutrophication. Algal blooms reduce light penetration, deplete oxygen during decomposition, and threaten aquatic fauna. Managing nitrogen inputs in watersheds is therefore critical to preserving water quality and aquatic biodiversity.

Human Impacts on the Nitrogen Cycle

Human activities have significantly altered the nitrogen cycle over the past century. Industrial nitrogen fixation for fertilizers, fossil fuel combustion, and deforestation have increased reactive nitrogen in soils, water, and the atmosphere. While this has improved agricultural productivity, it has also caused ecological imbalances, including:

- Soil acidification from excessive nitrogen deposition.

- Groundwater contamination by nitrates.

- Greenhouse gas emissions, including nitrous oxide (N₂O), contributing to climate change.

- Biodiversity loss in ecosystems affected by nitrogen enrichment.

Addressing these challenges requires sustainable nitrogen management strategies, including precision fertilization, crop rotation with nitrogen-fixing plants, organic amendments, and restoration of natural ecosystems.

Practical Applications and Management Strategies

Understanding the nitrogen cycle has direct implications for agriculture, environmental management, and policy:

- Sustainable Agriculture: Using nitrogen-efficient crop varieties, optimizing fertilizer application, and integrating legumes in crop rotations reduce nitrogen loss and environmental pollution.

- Waste Management: Treating livestock waste and municipal effluents can recover nitrogen for use as fertilizer while preventing water contamination.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Reforestation, wetland restoration, and maintaining riparian buffers can reduce nitrogen runoff, improve water quality, and enhance soil fertility.

- Climate Mitigation: Reducing nitrous oxide emissions through controlled fertilizer use and promoting natural nitrogen cycling can mitigate greenhouse gas impacts.

The nitrogen cycle is a critical process that sustains life on Earth by ensuring the continuous transformation and availability of nitrogen in forms usable by plants, animals, and microorganisms. From nitrogen fixation and nitrification to denitrification, ammonification, and assimilation, the cycle integrates terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, supports biodiversity, and underpins human food production. However, anthropogenic activities have significantly altered this cycle, leading to environmental challenges such as eutrophication, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions. By understanding the processes of the nitrogen cycle and implementing sustainable management strategies, humans can harness nitrogen’s benefits while minimizing its environmental impacts.

An actionable understanding of the nitrogen cycle empowers scientists, farmers, and policymakers to optimize nitrogen use, restore ecological balance, and ensure sustainable productivity for future generations.

References

Abrahams P.W (2006). Soil, geography and human disease: a critical review of the importance of medical cartography. Progress in Physical Geography, 30:490-512.

Ahring B.K, Angelidaki I and Johansen K (1992). Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci. Technol, 30, 241–249.

Andersson L and Rydberg L (1988). Trends in nutrient and oxygen conditions within the Kattegat: effects on local nutrient supply. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci, 26:559–579.

Ballantyne A.P, Alden C.B, Miller J.B, Tans P.P and White J.W.C (2012). Increase in observed net carbon dioxide uptake by land and oceans during the past 50 years. Nature, 488: 70-72.

Baumgardner D.J (2012). Soil-related bacterial and fungal infections. J Am Board Fam Med, 25:734-744.

Bennett E.M, Carpenter S.R and Caraco N.F (2001). Human impact on erodable phosphorus and eutrophication: a global perspective. BioScience, 51:227–234.

Bunting B.T. and Lundberg J (1995). The humus profile-concept, class and reality. Geoderma, 40:17–36.

Paul E.A (2007). Soil Microbiology, ecology and biochemistry. 3rd edition. Oxford: Elsevier Publications, New York.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Pelczar M.J., Chan E.C.S. and Krieg N.R. (2003). Microbiology of Soil. Microbiology, 5th Edition. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, New Delhi, India.

Pepper I.L and Gerba C.P (2005). Environmental Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. Second Edition. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, USA.

Roberto P. Anitori (2012). Extremophiles: Microbiology and Biotechnology. First edition. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, England.

Salyers A.A and Whitt D.D (2001). Microbiology: diversity, disease, and the environment. Fitzgerald Science Press Inc. Maryland, USA.

Sawyer C.N, McCarty P.L and Parkin G.F (2003). Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishers, New York, USA.

Ulrich A and Becker R (2006). Soil parent material is a key determinant of the bacterial community structure in arable soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 56(3):430–443.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.