Introduction

Microbial strain improvement is a critical process in industrial microbiology and biotechnology, aimed at enhancing the capabilities of microorganisms to produce valuable metabolites, enzymes, or biomass. It refers to a set of deliberate and strategic modifications—genetic, biochemical, or physiological—undertaken to enhance a microorganism’s performance under industrial conditions. These modifications are essential to ensure high yield, productivity, stability, and cost-effectiveness of industrial bioprocesses.

With the increasing global demand for bioproducts such as antibiotics, organic acids, amino acids, biofuels, vitamins, enzymes, and fermented foods, the need for robust microbial strains has never been more pressing. Wild-type microorganisms isolated from natural environments—although potentially metabolite producers—are often suboptimal for industrial application due to low yield, genetic instability, slow growth rates, or poor tolerance to environmental stressors. Strain improvement serves as a powerful strategy to overcome these limitations and align microbial capabilities with industrial needs.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of the concept of strain improvement, the characteristics of an ideal industrial microbe, various strategies used to enhance microbial strains, and the economic and technological significance of strain enhancement in industrial applications.

Understanding the Industrial Microbe

Desirable Traits of Industrial Microorganisms

Before delving into the processes of strain improvement, it is essential to understand the defining characteristics of microorganisms that are considered suitable for industrial applications. Industrial microbes are the backbone of numerous biotechnological processes, ranging from the production of antibiotics, enzymes, organic acids, biofuels, to vitamins and fermented foods. However, not every microorganism isolated from the environment is immediately ready for industrial deployment. Specific traits make a microbe particularly valuable and efficient for such applications.

A desirable industrial microorganism should:

- Produce the target product in high yield and concentration – The organism must synthesize the desired metabolite or compound in sufficient amounts to justify industrial investment. High yield ensures economic feasibility.

- Utilize inexpensive and readily available substrates – To lower production costs, the organism should be capable of metabolizing low-cost carbon or nitrogen sources, including agricultural residues or industrial waste streams.

- Grow rapidly under controlled fermentation conditions – Fast-growing microbes reduce the time required for production, increasing overall process efficiency.

- Exhibit genetic and metabolic stability over many generations – Stability ensures consistent performance and prevents genetic drift that might lead to loss of productivity during prolonged industrial operations.

- Resist contamination and environmental fluctuations – The microbe should thrive despite changes in temperature, pH, oxygen levels, or potential contamination, which are common challenges in industrial-scale fermentations.

- Be non-pathogenic and safe for large-scale handling – For the safety of personnel and consumers, industrial strains must be non-toxic, non-pathogenic, and pose minimal biosafety risks.

- Tolerate high concentrations of products or toxic intermediates – Many metabolites can inhibit microbial growth at high concentrations. A robust strain should withstand product toxicity and continue functioning efficiently.

Most wild-type microorganisms isolated from environments such as soil, water, compost heaps, or decaying biomass rarely exhibit all these desirable traits. As such, even after thorough screening, potential strains often require further enhancement. This is where strain improvement becomes indispensable—allowing scientists to tailor microbial characteristics to meet the rigorous demands of industrial processes.

The Need for Strain Improvement

Microorganisms used in industrial biotechnology and fermentation processes typically originate from natural isolates—microbes sourced directly from their native environments such as soil, water, or plant materials. While these wild-type strains may possess the basic capability to produce valuable metabolites, enzymes, or bioactive compounds, their innate production levels, growth rates, and metabolic efficiency often fall short of the demands of large-scale industrial applications. This natural limitation presents a significant bottleneck for cost-effective and sustainable bioprocesses.

For example, consider the wild strain of Penicillium chrysogenum, the original source of penicillin. In its native state, this fungus produced only trace amounts of penicillin, insufficient for commercial exploitation. However, through systematic and iterative strain improvement—combining classical mutagenesis, selection, and modern genetic engineering—industrial strains of P. chrysogenum have been developed that produce penicillin in quantities thousands of times greater than their wild counterparts. This remarkable enhancement illustrates the profound impact strain improvement can have on industrial microbiology and biotechnology.

Several key motivations drive the need for strain improvement in industrial microbes:

- Increased Productivity: By improving the genetic and metabolic capacity of microbial strains, the concentration of desired products can be significantly raised. This higher yield reduces fermentation time and increases throughput, directly lowering production costs and enabling more competitive pricing in the market.

- Improved Substrate Utilization: Wild microbes may require expensive or complex nutrients to grow efficiently. Through strain improvement, microbes can be engineered or selected to utilize cheaper, more abundant, or alternative substrates—such as agricultural wastes or industrial by-products—thus making the production process more economically and environmentally sustainable.

- Tolerance to Process Conditions: Industrial fermentations often involve harsh or fluctuating conditions, including extreme pH, high temperatures, osmotic stress, or toxic by-products. Native strains may be sensitive to these factors, resulting in inconsistent performance or batch failures. Strain improvement can enhance microbial robustness and stress resistance, ensuring stable and reliable fermentations.

- Reduced Production Costs: Enhanced strains consume substrates more efficiently and generate higher product titers, which translates into lower raw material usage, reduced energy consumption, and minimized waste. Collectively, these improvements decrease the overall cost of production and increase profit margins.

- Regulatory Compliance and Product Consistency: Industrial products, especially those intended for pharmaceutical or food applications, must meet stringent regulatory standards. Strain improvement helps produce genetically stable microbes that maintain consistent metabolic profiles over successive production cycles, ensuring uniform product quality, safety, and regulatory compliance.

Beyond these practical reasons, strain improvement also serves as a strategic tool for biotechnology companies. It provides a competitive edge by enabling faster, cheaper, and greener production processes while supporting the development of novel products and applications. As industries face increasing pressure to minimize environmental impact and promote sustainability, improved microbial strains become indispensable allies in meeting these goals.

In summary, strain improvement is essential not only for boosting microbial productivity but also for optimizing substrate use, enhancing stress tolerance, reducing costs, and ensuring regulatory and quality standards. Its role is pivotal in driving innovation and sustainability in industrial microbiology and biotechnology.

Strategies for Strain Improvement

Strain improvement can be broadly categorized into classical approaches and modern molecular techniques. Both aim to alter the genetic makeup or expression profile of microorganisms to optimize their industrial performance.

1. Classical Methods of Strain Improvement

Classical strain improvement techniques have been the backbone of industrial microbiology for decades, long before the advent of modern genetic engineering. These methods rely largely on natural processes or induced changes in microorganisms to enhance their industrially relevant traits such as metabolite yield, growth rate, or stress tolerance. Despite being time-consuming and often unspecific, classical approaches have been instrumental in developing many of the commercially successful microbial strains used in fermentation and bioproduction today.

a. Random Mutagenesis

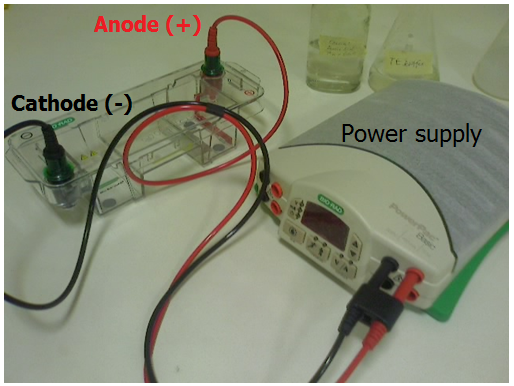

Random mutagenesis is one of the most widely applied classical approaches for strain improvement. It involves subjecting microbial cells to mutagenic agents that cause DNA damage, leading to random changes in the genetic code. These agents can be physical, such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation and X-rays, or chemical, including powerful mutagens like nitrosoguanidine (NTG) and ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS).

The primary advantage of random mutagenesis is its ability to generate a wide spectrum of genetic variants without prior knowledge of the organism’s genome. After mutagen exposure, a large population of mutants is screened to identify strains that show enhanced performance, such as increased production of antibiotics, enzymes, or organic acids. While this method is relatively unspecific and often labor-intensive due to the need for extensive screening, it has historically yielded some of the most successful industrial strains. For example, many high-yield penicillin-producing strains were developed by successive rounds of UV and chemical mutagenesis.

b. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE)

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution leverages the natural ability of microorganisms to adapt to environmental pressures over time. In ALE, microbial populations are cultivated under gradually intensifying selective conditions, such as increasing concentrations of substrates, toxins, or environmental stressors (e.g., high temperature or pH extremes). Over many generations, beneficial mutations accumulate, allowing certain strains to outcompete others under these selective pressures.

This method simulates natural evolutionary processes but within controlled laboratory environments tailored to industrial needs. For instance, ALE has been successfully applied to develop yeast strains with improved tolerance to ethanol or osmotic stress, crucial for bioethanol production. The key benefit of ALE is that it can reveal novel genetic adaptations and phenotypes that might be difficult to predict or engineer directly, resulting in strains better adapted to specific industrial conditions.

c. Protoplast Fusion

Protoplast fusion is a hybridization technique used to combine the genetic material of two distinct microbial strains. The process begins by enzymatically removing the rigid cell walls of bacteria or fungi to form protoplasts—cells surrounded only by the plasma membrane. These protoplasts from different strains are then induced to fuse, typically using polyethylene glycol (PEG) or electrical pulses, creating hybrid cells that contain genetic material from both parent strains.

This technique is particularly valuable when crossing strains that cannot sexually reproduce or when combining desirable traits from two different species. The resultant hybrids often exhibit enhanced or novel capabilities, such as improved metabolite production, increased substrate utilization, or greater environmental tolerance. Protoplast fusion has been widely used in fungal strain improvement, for example, to enhance enzyme secretion or antibiotic biosynthesis.

d. Selective Breeding

Selective breeding, or classical strain selection, is one of the simplest and oldest methods used to improve microbial strains. This process involves repeatedly culturing microbes and selecting those individuals or colonies that display superior traits, such as faster growth or higher product yield. These selected strains are then used as inoculum for the next round of cultivation and selection.

While selective breeding is a relatively slow and rudimentary method compared to other techniques, it remains relevant, especially for organisms where genetic tools are limited or for fine-tuning traits after other improvement methods. Over successive cycles, this can lead to gradual but meaningful improvements in strain performance. This method is often combined with mutagenesis or ALE to enrich populations with beneficial traits.

2. Modern Genetic and Biotechnological Techniques for Strain Improvement

The rapid advancements in molecular biology, genomics, and biotechnology have ushered in a new era of precision and efficiency in strain improvement. Unlike traditional methods that relied heavily on random mutagenesis and selection, modern techniques enable targeted, predictable, and often much faster modifications of microbial genomes. These approaches have transformed the landscape of industrial microbiology by allowing scientists to tailor microorganisms with specific desirable traits, improving yield, productivity, and overall industrial performance. Below are some of the key modern genetic and biotechnological techniques employed in strain improvement.

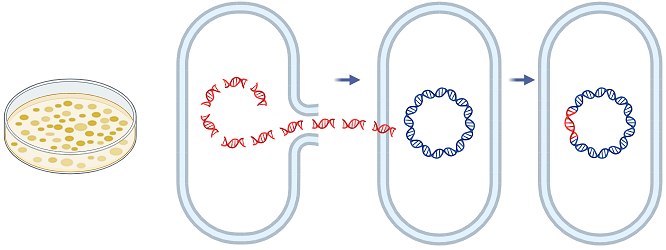

a. Recombinant DNA Technology

Recombinant DNA technology, often referred to as genetic engineering, involves the deliberate modification of an organism’s genetic material by introducing foreign genes or altering existing ones. This method allows for the enhancement or introduction of specific functions that are not naturally present in the host microorganism. For example, genes coding for enzymes like cellulases, which break down cellulose into fermentable sugars, can be inserted into yeast strains, enabling them to ferment plant biomass more efficiently. This capacity dramatically broadens the substrate range that an industrial microbe can utilize and improves production of biofuels and other biochemicals. Recombinant DNA techniques also facilitate the overexpression of rate-limiting enzymes in metabolic pathways, resulting in increased synthesis of desired metabolites such as antibiotics, amino acids, or vitamins.

b. CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas system represents a groundbreaking genome editing tool that offers unparalleled precision, efficiency, and versatility. This technology allows scientists to target specific DNA sequences within microbial genomes and make precise modifications—such as gene deletions, insertions, or replacements—without introducing off-target mutations that are common with older methods. CRISPR-Cas enables rapid and site-specific editing, making it a powerful tool for fine-tuning microbial metabolism. For instance, genes responsible for undesirable by-product formation can be knocked out, while pathways enhancing product formation can be activated or optimized. The ease of CRISPR technology also facilitates multiplex genome editing, where multiple genes are modified simultaneously, accelerating the strain development timeline.

c. Metabolic Engineering

Metabolic engineering is a sophisticated approach that involves the systematic redesign of cellular metabolic pathways to improve the flow (flux) of substrates toward the desired product. By employing genetic modifications such as gene overexpression, knockouts, or the introduction of heterologous pathways, metabolic engineers redirect cellular resources to optimize yield and productivity. This technique is particularly useful when native pathways compete for precursors or energy, limiting the production of target metabolites. For example, in antibiotic-producing microbes, competing pathways can be suppressed, while key biosynthetic enzymes are enhanced to maximize antibiotic output. Metabolic engineering often leverages computational modeling to predict the effects of genetic changes on cellular metabolism, enabling a more rational and efficient strain improvement process.

d. Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology integrates principles of engineering, molecular biology, and computational design to construct new biological systems or redesign existing ones from the ground up. In the context of microbial strain improvement, synthetic biology enables the creation of entirely new metabolic pathways, genetic circuits, or even whole synthetic genomes tailored to industrial needs. This approach allows for the development of microorganisms with novel capabilities, such as producing complex pharmaceuticals, biofuels, or biodegradable plastics that natural strains cannot efficiently generate. By modularly assembling standardized genetic parts (promoters, ribosome binding sites, enzymes), synthetic biology facilitates the design of strains with optimized regulation, robustness, and productivity under industrial conditions.

e. Omics-Based Approaches

Omics technologies—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provide comprehensive, multi-layered insights into the structure, function, and regulation of microbial cells. These approaches generate vast datasets that reveal gene expression profiles, protein abundance, metabolic fluxes, and regulatory networks. By integrating these data, researchers can identify bottlenecks, limiting steps, and stress responses within microbial systems. This knowledge is crucial for guiding rational strain engineering efforts, enabling the targeted manipulation of genes or pathways most impactful for improving production traits. For example, transcriptomic analysis may reveal under-expressed enzymes crucial for metabolite synthesis, which can then be upregulated through genetic engineering. Metabolomics can detect accumulation of toxic intermediates that inhibit growth or production, guiding the design of more balanced metabolic pathways.

Examples of Strain Improvement in Industry

1. Antibiotic Production

Penicillin production is a classic case. The initial Penicillium strain isolated by Alexander Fleming produced extremely low quantities of penicillin. Through successive rounds of mutagenesis and selection, strains were developed that produced up to 1,000-fold higher yields. Similar approaches have enhanced the production of streptomycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and other antibiotics.

2. Amino Acids and Organic Acids

Corynebacterium glutamicum, a workhorse for amino acid production, has undergone extensive strain improvement to produce high levels of glutamic acid and lysine. Likewise, Aspergillus niger strains used for citric acid production have been optimized for productivity and substrate utilization.

3. Enzyme Production

Industrial enzymes such as amylases, proteases, cellulases, and lipases are produced using improved strains of Bacillus, Aspergillus, and Trichoderma. These strains are tailored for high enzyme titers, thermostability, and activity over wide pH ranges.

4. Biofuels and Bioplastics

Strains of Zymomonas mobilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Escherichia coli have been engineered to improve ethanol, butanol, and lactic acid production, key intermediates in biofuel and biodegradable plastic manufacturing.

Significance of Strain Improvement

Strain improvement holds a pivotal position in industrial microbiology and biotechnology, serving as a cornerstone for the advancement of industrial processes involving microorganisms. Its significance spans multiple dimensions, all contributing to the efficiency, sustainability, and profitability of microbial-based production systems.

1. Enhanced Productivity and Yield

The foremost and most tangible advantage of strain improvement is the marked increase in productivity. By genetically or physiologically modifying microorganisms, it is possible to boost their capacity to produce the desired metabolites—whether enzymes, antibiotics, organic acids, or biofuels—at significantly higher levels. This increased yield translates directly into improved industrial output, enabling companies to meet market demand more effectively and profitably.

2. Reduced Production Time and Cost

Optimized strains typically grow faster and convert substrates more efficiently, which shortens fermentation cycles. Faster growth rates and higher metabolic efficiency reduce the time required to reach the desired product concentration, thereby cutting operational costs. Moreover, improved strains often require lower quantities of raw materials and energy inputs to achieve the same or better yields, leading to significant savings on substrates, utilities, and labor.

3. Greater Process Robustness and Stability

Strain improvement enhances the robustness and stability of microbial cultures during industrial fermentations. Improved strains tend to perform consistently across multiple production batches, minimizing batch-to-batch variability. This consistency is crucial for maintaining product quality, meeting stringent regulatory standards, and ensuring customer satisfaction. Stable strains are also less prone to genetic drift or loss of productivity during prolonged industrial use.

4. Expansion of Substrate Utilization

Through strain improvement, microorganisms can be engineered or selected to metabolize a broader range of substrates, including cheap, renewable, or waste materials such as agricultural residues, molasses, glycerol, and lignocellulosic biomass. This substrate flexibility not only reduces feedstock costs but also contributes to sustainability by valorizing waste streams that would otherwise pose disposal challenges.

5. Environmental Sustainability

Modern industrial processes emphasize eco-friendliness and sustainability. Improved microbial strains contribute by lowering the overall environmental footprint of bioprocesses. Enhanced strains often require less energy and raw materials, generate fewer byproducts and waste, and can even be tailored to biodegrade pollutants or convert industrial residues into valuable products. This aligns with the growing global push for green technologies and circular bioeconomies.

6. Industrial Competitiveness and Innovation

In competitive sectors such as pharmaceuticals, food and beverages, bioenergy, and specialty chemicals, possessing proprietary, high-performing microbial strains offers a decisive market advantage. Strain improvement drives innovation by enabling the development of novel products, improving existing ones, and reducing production bottlenecks. Companies with superior strains often achieve faster time-to-market and better scalability, strengthening their competitive position.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the benefits, strain improvement faces several challenges:

- Regulatory hurdles, especially for genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

- Strain degeneration over time, which can lead to reduced productivity.

- Unintended metabolic burdens from excessive genetic modifications.

- Difficulty in predicting complex interactions in metabolic engineering.

However, the future of strain improvement is bright. Integrating machine learning, artificial intelligence, and systems biology into strain development is expected to accelerate innovation. Automation of screening processes and the use of microfluidics will allow high-throughput identification of elite strains. Moreover, the convergence of synthetic biology with evolutionary engineering will open new avenues for creating super strains tailored for next-generation industrial processes.

Conclusion

Microbial strain improvement is at the heart of modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. It transforms low-yielding natural isolates into powerful microbial factories capable of delivering high-value products efficiently and sustainably. Whether through classical mutagenesis or cutting-edge genome editing, the goal remains the same: to enhance the productivity, stability, and economic feasibility of microbial bioprocesses.

As the global economy shifts toward bio-based industries and sustainable production models, the importance of microbial strain improvement will continue to grow. It is a dynamic field that bridges microbiology, genetics, biochemistry, and engineering—fueling innovation in health, agriculture, energy, and the environment.

References

Bader F.G (1992). Evolution in fermentation facility design from antibiotics to recombinant proteins in Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st century (eds. Ladisch, M.R. and Bose, A.) American Chemical Society, Washington DC. Pp. 228–231.

Nduka Okafor (2007). Modern industrial microbiology and biotechnology. First edition. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Das H.K (2008). Textbook of Biotechnology. Third edition. Wiley-India ltd., New Delhi, India.

Latha C.D.S and Rao D.B (2007). Microbial Biotechnology. First edition. Discovery Publishing House (DPH), Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

Nester E.W, Anderson D.G, Roberts C.E and Nester M.T (2009). Microbiology: A Human Perspective. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Pelczar M.J Jr, Chan E.C.S, Krieg N.R (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Prescott L.M., Harley J.P and Klein D.A (2005). Microbiology. 6th ed. McGraw Hill Publishers, USA.

Steele D.B and Stowers M.D (1991). Techniques for the Selection of Industrially Important Microorganisms. Annual Review of Microbiology, 45:89-106.

Summers W.C (2000). History of microbiology. In Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 2, J. Lederberg, editor, 677–97. San Diego: Academic Press.

Talaro, Kathleen P (2005). Foundations in Microbiology. 5th edition. McGraw-Hill Companies Inc., New York, USA.

Thakur I.S (2010). Industrial Biotechnology: Problems and Remedies. First edition. I.K. International Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India.

Discover more from Microbiology Class

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.